The relationship between scaling and systems change has been much debated within the scaling literature over the last few years. Those who focus on systems change, have argued that most scaling efforts are flawed because they ignore or underappreciate the role of systems. Too often they narrowly consider only how to increase the number of adopters or users of a specific technology or product while ignoring the organizational and institutional context that is necessary for those technologies to have sustainable impact at scale. Going even further, some critics argue that rather than pursuing scaling of a specific solution, the focus should be on the changes in the social, political, technical, institutional, and policy environment, i.e., the “system”, to address broad global challenges like the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this view, scaling innovations can be a part of a broad set of solutions, but only one tool in the toolkit, and probably not even the most important. Moreover, despite the claim by innovators that their innovations are disruptive or game-changing, critics argue that the degree of change implied by scaling innovations, even when accompanied by some systems considerations, is usually too incremental compared to the problems being addressed. Moreover, so the argument goes, because scaling pays insufficient attention to systems at best it leaves in place the existing inequality and power imbalances embedded in those systems and at worst reinforces and strengthens those inequities.

With this critique of scaling as backdrop, The Scaling Community of Practice (CoP) decided to delve more deeply into the question what scaling and systems change have in common and where they differ. The CoP commissioned an issues paper and organized two webinars to address this question. In making this comparison, we tried to avoid a straw man or caricaturizing either view. For example, while it is true that in practice many scaling efforts ignore systems constraints, that is certainly not true of most guidance or thoughtful writers on the topic.

Scaling and systems change share the goal of bringing about large-scale change. That said, they do differ in a number of important areas. First, they have different starting points: scaling starts with an innovation or intervention, which could include an organizational or institutional innovation, and asks how it and its impact can be scaled. Systems change starts with the entire relevant ecosystem and asks how it needs to change to achieve impact at scale; one is micro or bottom-up in its theory of change, the other is macro or top-down. Scaling sees innovation as the focal point for change, systems change sees innovations as one of many potential change levers.

A second area where the two approaches diverge is the degree of systems change considered desirable or necessary. The scaling literature is often rooted in the view that any type of change is hard, whether in the behavior of individuals and groups, organizations, or institutions; change becomes harder at large scale, and gets multiplicatively or even exponentially more difficult the greater the degree of change from the status quo. Therefore for reasons of both feasibility and resources, in the scaling world, while systemic aspects are recognized as important enabling or constraining factors, there is a tendency to keep the degree of systems change to the minimum necessary to achieve sustainable impact at large scale. This view is reinforced by the view that comprehensive and deep systems change takes an enormous amount of resources and time (often measured in decades). Scaling proponents argue that while broad systems change is often particularly appealing to academics, especially those who are students of systems and complexity, or in the strategies of large donors or multi-lateral institutions, where it seems to serve as much as a framing device and aspirational “call to arms”, in neither case is adequate consideration given to the implications in terms of time, resources or feasibility. Given the urgency of global issues, systems change is simply impractical; as it is, scaling usually takes 5-15 years and that itself already proves to be a major challenge. Therefore, scaling advocates believe it is generally easier to modify the innovation to align with existing systems constraints or to address a few particularly important systemic factors, rather than to work towards changing entire ecosystems.

By contrast, many systems change proponents would argue that this limited view of systems change is exactly the problem. Without a significant and comprehensive understanding of and changes to existing systems, even if scale reaches large numbers, the impact on the challenge being addressed will ignore issues of complexity, second-order effects, and unanticipated impact. Any or all of these factors can and often do undercut or even reverse the impact of scaling. This, so the argument goes, is particularly problematic if one recognizes that many global challenges are multi-sectoral and multi-dimensional. For example, agriculture implicates food, nutrition, health, environmental sustainability, climate change, resilience and gender, to name but a few. While it is true that multi-sectoral and multi-dimensional issues are complicated and addressing them resource and time-consuming, all the more reason to stop wasting resources on partial solutions and incremental change that pay no attention to the complex reality. By ignoring all of these factors, scaling has marginal or incremental impact when transformational change is what is required.

These differences between the scaling and the systems change approaches have practical implications. Systems change usually calls for some combination of (greater) systems mapping and analysis as well as increased participation and inclusion. Taken together, these usually imply some form of ongoing, inclusive, comprehensive multi-stakeholder process for defining the problem(s), setting a vision and goals, and developing a system-wide strategy and action plan. For systems skeptics, systems mapping and participation sounds good in principle and some should be done in practice. Indeed, it has become a foundational assumption of scaling that the needs of the end user and constraints on funding and implementation capacity at scale need to be taken into consideration from the very beginning, preferably by including end users and large-scale implementers and funders in the innovation and scaling process. However, the scaling community would tend to limit this to those systems constraints and stakeholders most directly concerned, rather than expanding the analysis and consultation process to the system as a whole. Engaging with the entire system and all stakeholders is seen as unrealistic in the presence of the weak governance and funding and human resource constraints that by definition characterize low resource environments. From this perspective the risk of a systems approach is that it quickly leads to paralysis by analysis: those diagrams with all the squares, circles and other shapes with dozens of crisscrossing arrows showing all the relationships become overwhelming rather than a useful input into goals, vision and strategy. For proponents of scaling, dealing with systemic constraints and opportunities as they become relevant along the scaling pathway is the more practical way to proceed; indeed, when done right, scaling eventually will lead to necessary systems change once sufficient scale is reached.

This debate helps focus the conversation; rather than talking about scaling versus systems change, one should be exploring whether and how scaling and systems change complement each other, and how

much systems change is appropriate. The reality is that scaling has to consider the ecosystem within with it takes place, and a systems approach has to consider whether and how much system change is feasible in a given context. Similarly how much systems analysis and change is practical to support even a more ambitious approach to scaling of specific innovations or interventions, e.g., one that takes on issues of inequities and unexpected or second-order effects.

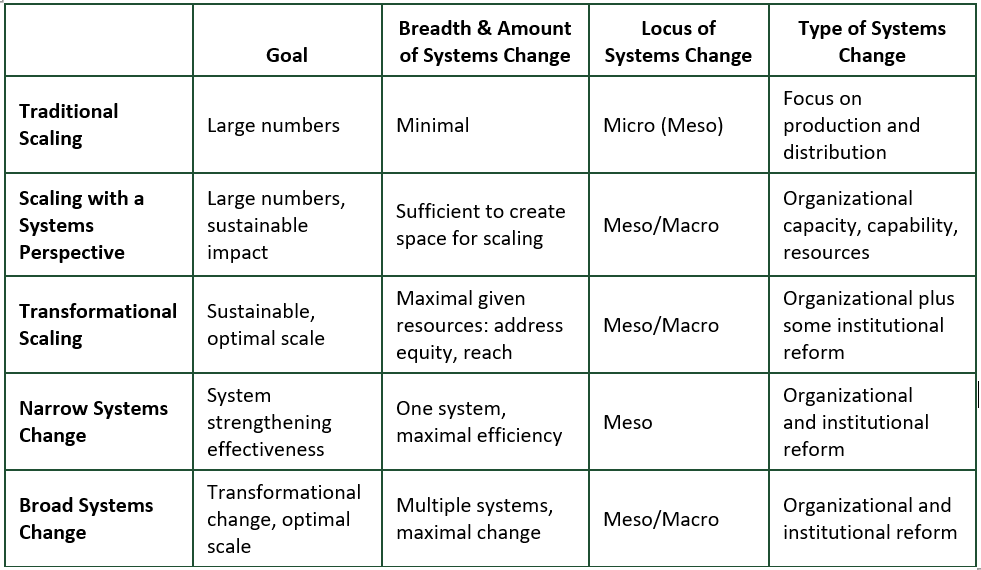

For both scaling and systems change approaches, it will help to talk about the extent, breadth, depth and locus, and type of systems change and their practical implications. In terms of the extent of systems change, are we talking about incremental, reform or transformative change? In terms of breadth, one change or many changes – to one system or to a number of (presumably interrelated) systems? In terms of the depth and locus of change, are these changes at the micro/individual level, at the macro level, or somewhere in between (meso level)? Last but perhaps most importantly, what is the type of systems change, is it organizational or institutional change? Organizational change has more to do with what is tangible or technical, what is often associated with capacity building, e.g., better computer or accounting systems, internal processes and procedures, accountability mechanisms and incentives. These tend, by definition to be tied to a specific organization like a ministry, public hospitals and clinics, etc. By contrast, institutional changes target altering the rules, power relations, beliefs, mindsets, and social norms.

With these questions about the nature of systems change in mind, we have developed a typology of five approaches to large scale change differentiated in four ways by type of goal and by type of systems change. (Note this typology is not meant to be comprehensive but illustrative.)

Note: For a detailed explanation of each approach see Box 1 in the issues paper on scaling and systems change.

The five approaches span the spectrum from the most limited form of scaling to the broadest form of systems change. Which of these are preferred will depend on three factors: (1) the challenge being addressed, including the context; (2) the resources available to support change; and, most importantly, (3) who is the actor pursing impact at scale. Where you are situated in the system and what are your function, reach and resources will be a key determinant of which approach you can and should adopt. A private entrepreneur, a mayor of a town, an NGO or small funder will likely have to focus on the simpler scaling options, preferably one that takes into account systems constraints. A minister in government or a large funding organization would be able to pursue transformational scaling or narrow systems change. Broad systems change may be feasible for national governments, large donors or multi-lateral institutions that have the resources required. The challenge remains to align the approach with both the size, scope and urgency of the problem and the resources available, financial and organizational.