It’s as if someone suddenly flipped a switch. Discussions about scale and scaling, previously considered esoteric topics, now appear in almost every conversation about ending poverty, saving lives, or protecting the planet. Whether focused on social enterprise or governmental action, social investment or fortunes at the base of the pyramid, these conversations acknowledge the need to confront explicitly the obstacles that stand between successful pilot projects and the solution to population-level problems.

As two people who have worked on the issues of scale and scaling for more than a decade , we are pleased at the attention the issue of scale is receiving. But we believe that there is a central element missing from many of these discussions. That element relates to overcoming predictable obstacles that innovations face when moving from the margin to the mainstream.

At one end of the “supply chain”, support for innovation enjoys robust funding, strong institutions, and widespread success witnessed in the proliferation of innovation hubs and grand challenges. At the other end of the chain, markets and governments have structures and funding models that allow them to deliver goods and services sustainably at scale. But these two parts of the chain are separated by a broken link. We refer to this broken link as “intermediation” and it is the subject of this paper.

The Ingredients of Intermediation

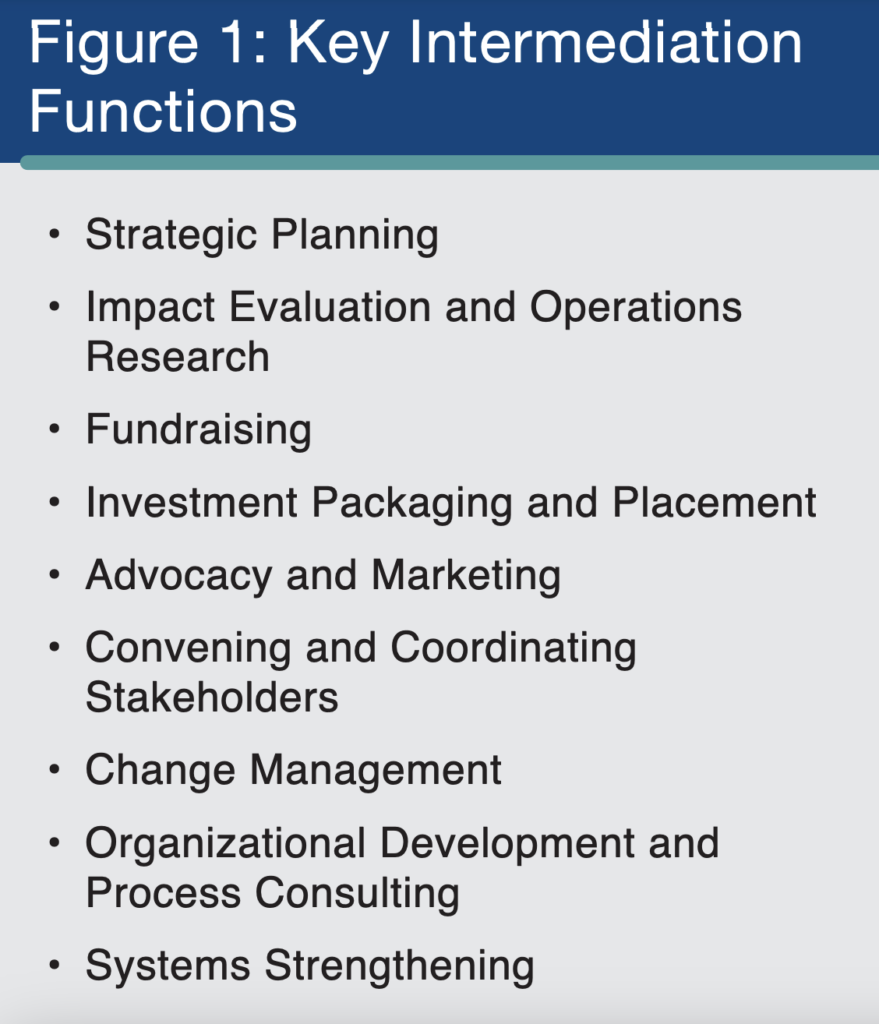

When we use the term “intermediation,” we refer to functions such as those listed in Figure 1 below:

Rarely do innovators, R&D units, social entrepreneurs or governments perform these functions on their own. In the case of fully commercial consumer goods, a variety of specialized institutions — investment bankers, impact investors, venture capitalists and consultants – have evolved to fill the niche. These intermediaries become, in effect, the “clutch” that connects the twin gears of innovation and population-scale service delivery

Rarely do innovators, R&D units, social entrepreneurs or governments perform these functions on their own. In the case of fully commercial consumer goods, a variety of specialized institutions — investment bankers, impact investors, venture capitalists and consultants – have evolved to fill the niche. These intermediaries become, in effect, the “clutch” that connects the twin gears of innovation and population-scale service delivery

Funding for intermediation functions in the private sector is financed from profits or expected high returns. Venture funds or impact investors usually provide substantial technical assistance in addition to capital, relying on their own experience within the sector they are investing. In addition, consulting firms like McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group and others compete to support the intermediation function in high-growth, high-margin organizations.

Unfortunately, these institutions and this part of the innovation supply chain do not translate well into the world of social outcomes. Possessing neither the glamor of innovation, the immediacy of direct service delivery, or the prospect of charging and recovering significant transactional returns, funding for these intermediation functions – with a few notable exceptions — falls between the stools.

There’s a second key difference between fully commercial consumer goods and social outcomes that compounds the challenges of reaching scale and makes the performance of key intermediation functions even more important. When consumer goods and services go to scale, the binding constraint is usually on the demand side and scaling usually involves diffusion of innovation, contagion (“going viral”). By contrast, the binding constraint in scaling social outcomes often lies on the supply side where need does not reliably trigger supply, where decisions by governments and third party funders stand between supply and demand, and where a single-supplier model often operates. This reflects a classic “principal/ agent” problem where beneficiaries are not in a position to pay for the services directly, and the government provides the service without the checks and balances that are always present with the ability to pay.

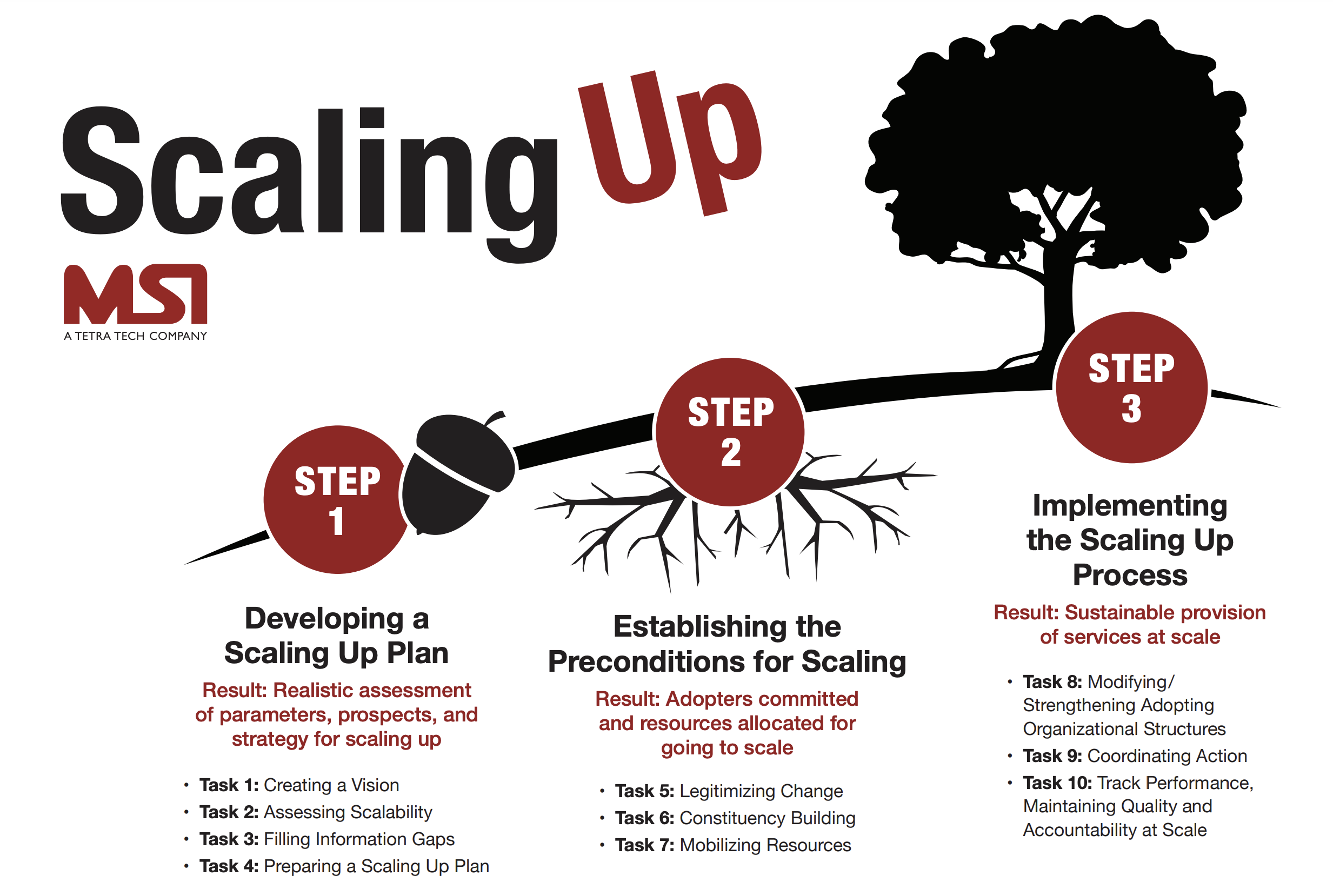

The differences between incentives and returns in the private sector and the public sector have significant implications for the role, incentives and functions of intermediary organizations supporting the scaling of social outcomes. We have argued elsewhere that scaling up can be seen as a 3-step, 10-task process (see Figure 2 below).2 The first step focuses on planning for scale, the second step focuses on galvanizing the needed support, and the third step focuses on carrying out a disciplined change management process.

Intermediation takes different forms during each of these steps. During Step 1 — the “planning” step – key intermediation functions include strategic planning, impact evaluation and operations research. During Step 2 – the “political” step – the focus of intermediation shifts to convening and coordinating stakeholders, fundraising, investment packaging, advocacy and marketing. And during Step 3 – the “operational” step – the emphasis is on change management, organizational development, and systems strengthening. Support for process consulting is needed during each of the steps.

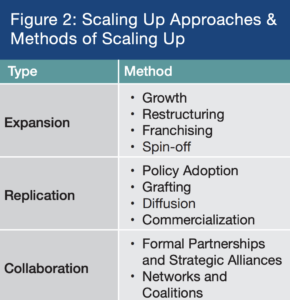

Just as intermediation functions differ at each stage of the scaling up process, they also differ based on the strategy for achieving scale. MSI’s research and operational experience suggest that there are 10 alternative methods or strategies (what Johannes Linn refers to as “pathways”) by which social interventions reach scale (see Figure 6 below).3 These methods are grouped into three categories – Expansion, Replication, and Collaboration.

Expansion refers to taking a model to scale by increasing the scope of operations of the organization that originally developed and piloted it. The most common form of expansion is growth, which normally occurs by branching out into new locations or target groups. Sometimes this growth is accompanied by decentralization or restructuring, which places special demands on the originating organization. Two other methods of expansion are franchising of the model to organizations operating as agents or clones of the originating organization, and spinning off aspects or parts of the originating organization to operate independently.

Replication involves the increased use of a particular process, technology, or approach by getting others, including the public sector, to adopt and implement that model. One of the most common types of replication is policy adoption, where a model is scaled up from a pilot run by an NGO, community group, or private company to a program or practice mandated and often run by the public sector. Two other common forms of replication are grafting, where a model –– or one component of a model –– is incorporated into another organization’s array of services or methods of service delivery and commercialization, where private entities take over the model on a forprofit basis. In addition to these more deliberate scaling up methods, replication sometimes occurs spontaneously. While spontaneous replication is common in the private sector where profit provides the necessary incentive, cases of spontaneous replication of new models of service delivery are much less common in the non‐profit and public sectors, and rare at the base of the pyramid.

Collaboration, the third method for scaling up, falls somewhere between the expansion and replication approaches. Collaboration mechanisms run the gamut from formal partnerships to informal networks and include a number of innovative structures and governance arrangements. Formal partnerships and strategic alliances are increasingly common methods for organizing collaborative efforts, as are less formal networks and coalitions based on memoranda of understanding or merely a handshake. Typically, these arrangements include some division of responsibility among the collaborating organizations. The recognition by private firms of commercial opportunities among the poor, and a growing emphasis on corporate social responsibility, have greatly expanded opportunities for these types of partnerships.

In the case of Expansion, intermediation is especially important in helping organizations plan for and digest growth. Changes in the basic business model, financial management, leadership team, internal systems, and training regimes figure prominently in this process. In the case of Replication, the focus is on transfer of an innovation from its originator to another entity better able to deliver at scale. In this case, the ability to convene prominent stakeholders, mobilize support, market ideas, and negotiate differences loom large as intermediary functions. And where scaling takes place through Collaboration, support for the development, negotiation and instituting of shared value models, multi-stakeholder governance, and flexible accountability systems are particularly prominent intermediation functions.

There are, we believe, only two “institutions” – commercial markets and governments – that can meet the twin tests of delivering services sustainably and at scale. Each of these two institutions has the delivery network, the funding base, and the incentive structure to deliver in perpetuity to large populations.4 NGOs, Social Enterprises, Community Based Organizations, philanthropies and other civil society groups play important roles in fostering new solutions and meeting the needs of modest-size populations, but only rarely can they deliver and/or finance services to large populations over extended periods without engaging markets and/or governments. Intermediation, in this context, means helping to promote adoption of improved practices by government agencies and/or by private companies, and persuading governments or citizens to pay for those services. Our experience suggests that relatively few grassroots or social entrepreneurs and even fewer governments, have the skill set or inclination to perform the full set of intermediation functions needed to take innovation to scale. More surprisingly, large private sector entities frequently contract out many of these functions as well.

As noted above, these intermediation functions are provided in well-developed commercial markets by specialized institutions on either a fee-for-service or benefit-sharing model; and payment for those services is baked into the way markets operate. In the social sector, the market for third-party performance of intermediation functions fails to operate in the same way; and that problem is especially acute at the BoP, where the ability to price these services into the cost of goods and services is particularly limited. In these settings, intermediary organizations often find themselves unable to pass the cost of their operations on to either the organization doing the innovating or the organization that potentially delivers the service at scale.

We learned about this problem the hard way. Both of us have worked over the years with helping grassroots organizations and host country governments scale major reforms and innovations, often with funding from third-party donors and philanthropies. Across a wide range of sectors and countries, we consistently found an abundance of talented actors developing and funding potentially attractive innovations. We also found governments and businesses able and willing to provide improved products and services to their clients. But in case after case, we found gaps in one or more of the key intermediation services that resulted in failure to scale up important initiatives.

In our view, this market — and government– failure suggests a new and important role for donors and other third parties seeking to catalyze change. By focusing attention on improving business models and indigenous capacity to perform key intermediation functions, donors can help to repair a broken piece of the innovation supply chain and help to provide the “clutch” that allows the gears of innovation and service delivery to mesh in a way that drives meaningful change at scale.

Intermediation at the Base of the Pyramid

As we noted above, we believe the gaps in key intermediation functions are especially limiting for programs and organizations that focus their programming at the Base of the Pyramid. This observation is based on our personal experience working with a number of the grassroots organizations, including many of the world’s most legendary. Helping them to identify and overcome the obstacles they face in scaling up their most effective programs. These organizations create an abundance of innovative interventions successfully targeting some of the most stubborn behavioral issues standing in the way of poverty elimination. But in spite of these successes, many of them struggle to reach the scale needed to make a dent. What is missing, in our view, is the financing and institutional capacity needed to perform the intermediation roles necessary to reach scale.

Take the case of SEWA, the Self Employed Women’s Association headquartered in India. SEWA is an internationally-acclaimed organization that reaches 2 million Indian women, owned and managed by its members. SEWA has helped large numbers of women fight poverty and is an inspiration for other grassroots organizations around the world. Over the last 40 years, SEWA has scaled up its membership, its geographical reach and the number of trades it covers. Today, SEWA covers 122 trades, including: • Street vendors of vegetables, fruit, fish, eggs, household goods and clothes • Home-based workers: weavers, potters, bidi workers, papad rollers, garment workers • Manual laborers: agriculture, construction workers, handcart pullers, head – loaders, domestic workers and laundry workers. • Small Producers: farmers, cattle rearers, salt workers.

By many standards, SEWA is a huge success, but – to their credit – they measure themselves not only by the people they serve (the “numerator”), but also by the size of the population in need (the “denominator”). And that vision drives SEWA’s ambition to grow their impact.

IMAGO Global Grassroots has been working for several years with SEWA, on a shoestring budget, providing various intermediation functions and serving as co-creators of SEWA’s scaling-up strategy. This strategy for scaling relies almost entirely on Expansion – i.e., growing SEWAs’ organizational footprint and range of services. SEWA has chosen to do this without departing from their essential organizational model and philosophy which rely on ownership and management by its members. These decisions carry with them a range of specific intermediation challenges.

Because SEWA opted for scale through expansion, its scaling up depended heavily on the ability of the organization and its leadership to adapt to the new demands likely to come from rapid growth in its staff, selective modernization of its management systems, and additional quality control procedures needed to handle a doubling of their volume. These are precisely the kinds of changes donors are reluctant to fund and organizations like SEWA are unable to finance.

IMAGO was brought on to help to play the intermediation role. Given the focus on organizational change, Strategic Planning was the first intermediation function IMAGO carried out with SEWA. Starting by identifying the organization’s future potential, understanding initial conditions (strengths and weaknesses), and drawing a path of what would be necessary to scale up from 2 million to 4 million women. The strategy work allowed the management team and SEWA’s Executive Committee to understand the strategic tensions, the many competing activities, and the need to focus on the critical path for scaling up.

Given the day-to-day urgent pressures, this work needed the support of an external organization that could hold the group together in a safe space, bring the voices of the different stakeholder through focus groups, and make sure the women that own SEWA were able to confront the difficult choices necessary to scale up with limited resources.

The main challenge that was identified in preparing SEWA for expansion was the need to strengthen systems: HR, IT, accounting, financial management, and data for evaluation. An organizational scan was part of the intermediation function both as a diagnosis and as part of a multi-year business plan. SEWA’s executive committee — mostly formed by previously illiterate women — understood the importance of systems strengthening and the need to undertake some change management within the organization to prepare for a larger scale, but here again would have been unlikely to undertake these changes without the engagement of a neutral third party.

Once they had a clear work plan and identified resource needs, IMAGO helped SEWA prepare proposals for fundraising. They initially thought this would be relatively straightforward given the extensive donor support SEWA receives for many different programs for their considerable array of services to the poor. But funding for systems strengthening proved to be extremely difficult to secure and would have been virtually impossible to find in the absence of strong intermediation.

The intermediation requirements associated with setting up an enhanced monitoring and evaluation function for SEWA is another area that SEWA and IMAGO targeted for attention. To meet the current needs of its 2 million members and to grow, SEWA needs to invest in a Membership Management System that will allow the organization to report about its members, track where they are growing, discern their needs, and go beyond relying on their staff’s “eyes and ears” as they move to millions of members across many locations.

The organization also needs to invest in tracking the impact of its interventions on the lives of its members. More specifically, SEWA has 11 development outcomes that have been identified by their members as the measure of their success as an organization.

There is technology today that would allow for easy tracking of all of this information, but it involves considerable start up challenges and needs substantial funding to meet the needs of current and future members. Even if start-up and system conversion costs can be kept to 2 dollars for each of SEWA’s current members, this adds up to a $4m investment, which is way beyond anything SEWA can self-finance. The intermediation function IMAGO played in this case is that of trusted advisor helping to make the case for the needed funding, helping to define the IT requirements, inviting firms to bid and evaluating the best proposal.

Beyond its service delivery to members, SEWA has invested in a wide range of Social Enterprises to provide employment to their members. Many of these enterprises are profitable for their members, but these profit centers (cooperatives producing items including textiles, spices, paper products, and construction) have nevertheless been unable to mobilize the capital needed to grow and to bring in professionals to help them scale up. In this case, the intermediation task was to help SEWA attract capital and build the capacity needed for the management of these profit centers. Although these functions enhance SEWA’s profitability, margins were insufficient to incentivize investment bankers, venture capitalists or private consultants to perform these functions.

Each case is, in many ways, unique in its intermediation needs. The principal variables that shape those needs are public vs private sector scaling, choice of scaling pathway (expansion, replication, collaboration), and the skill sets already present in the organization responsible for developing and testing the innovation. It is our intention to document a number of such cases and we encourage others to do so as well. But in each case we have looked at, major gaps in the provision of intermediation functions limit scaling at the base of the pyramid.

As we work with other organizations that want to scale up successful innovations, we find these and similar gaps across the board. There is funding available for innovation, looking for the next breakthrough. The real constraint is support and funding for the intermediation functions needed for organizations to scale up solutions that are already succeeding in reaching the poor. These scaling up challenges are predictable obstacles that innovations face when moving from the margin to the mainstream. We see them again and again in some of the best grassroots organizations in the world. Overcoming them is, we believe, a crucial missing link.