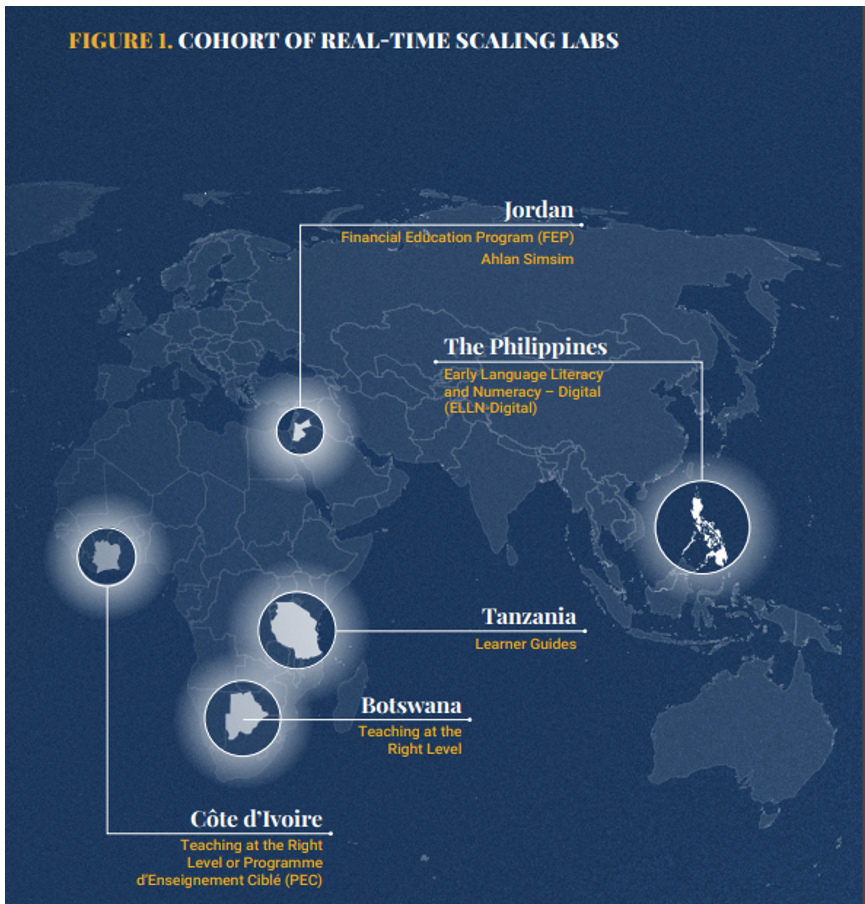

Too often, the complex multistakeholder work of scaling is not captured by typical monitoring and evaluation or research studies, and lessons learned are not systematically documented. In response, in 2018 the Center for Universal Education (CUE) at Brookings launched a series of Real-time Scaling Labs (RTSL) to generate more evidence and provide practical recommendations on how to expand, deepen, and sustain the impact of education initiatives leading to transformative change in education systems, especially for the most disadvantaged children and youth.

This blog shares findings from a new report, Scaling impact in education for transformative change: Practical recommendations from the Real-Time Scaling Labs, that looks across all data from six of the RTSL cases to analyze common themes, insights, and lessons learned about the process of scaling as well as interesting divergences, and to offer considerations for others looking to learn from or build on this work. The report’s findings draw from five years of participatory research and are organized at different units of analysis to explore the ways scaling happens at the system, institution, and individual levels. This blog provides a deep dive into two key system-level lessons. Unless otherwise cited, data throughout this report comes from firsthand documentation and analysis collected by RTSL scaling lab researchers and partners between 2018-2023.

Lesson 1: Operating in a system requires balancing tradeoffs, priorities, and opportunity costs

Across all the RTSL cases, a key scaling strategy was finding ways to align with the local policy environment. This allowed implementers to demonstrate how their initiative responded to local needs and/or contributed to key policy priorities.

- For example, in the Philippines, the development and scaling of a teacher professional development (TPD) initiative was a direct response to a priority policy of the Department of Education, who developed the Early Language Literacy and Numeracy Program from kindergarten to grade 3 in 2015. The Department of Education asked local NGO FIT-ED to co-develop and test a blended model of TPD delivery utilizing the original course content and leverage School-based Learning Action Cells. The pilot delivered the course successfully to over 4,000 teachers in 11 of the 17 national regions, and as a result, the Department of Education mandated national scale-up beginning in the school year 2019-2020.

- In Jordan, the International Rescue Committee began scaling efforts by first collaborating with the ministries and communities to identify priority needs and align these needs with existing national policies. With this shared understanding, only then did IRC collaboratively identify the core components of their Ahlan Simsim program that could help address these priorities. All partners engaged identified that as a first step, Ahlan Simsim’s social and emotional learning (SEL) and Learning through Play (LtP) approaches could be incorporated into the existing national School Readiness Program and reach marginalized children who did not attend preschool to help equip them to thrive in primary school.

Ideally local needs and national priorities are aligned, but in reality, they can and do diverge. Given the constant paucity of time as a resource, many scaling teams could not put equal focus and energy on every component of the education system at once and so they often had to decide where to prioritize their efforts. While all cases sought to address local needs and align with national priorities, in some cases the strategy was to start with grassroots-level priorities and work out and up, while in other cases, the first step was to emphasize issues that national or regional policymakers prioritized. Although these choices were necessary and often unavoidable, they often contributed to implementation challenges, imbalances, or blind spots that later had to be corrected.

- For example, in Jordan, the national government and the financial sector both identified strong need for greater financial literacy and inclusion among the population and youth in particular. This interest was reinforced by an international movement in favor of financial inclusion and resulted in the adoption of a Jordanian National Financial Inclusion Strategy. However, there was less interest from some teachers and students in the beginning, which led to some challenges with the quality of FEP delivery. Recognizing the need to rebalance the demand and establish greater support at the classroom level, the RTSL focused on identifying activities to strengthen teacher training and ultimately increase student and teacher engagement.

- The opposite occurred in Tanzania, where communities highly valued the Learner Guide program and its focus on opportunities and empowerment for adolescent girls. There was strong attention to a grassroots scaling approach, but initially less emphasis on cultivating buy-in at the higher levels of the education system and on articulating how the Learner Guide approach would fit into national policies and priorities. The RTSL supported CAMFED to introduce the program to a broader set of national policymakers and to find ways to align the program with existing policies for youth empowerment.

Lesson 2: Prioritizing costing and securing financing is challenging

In every case and among nearly every actor in the RTSLs, there was a strong awareness about the need for cost data to inform scaling decisions and the necessity of planning for sustainable medium- and long-term financing. Yet despite clear understandings of the importance of costing, this was an area with some of the greatest constraints and challenges when it came to operationalization. A primary obstacle was lack of data. In many instances, the detailed and disaggregated data necessary to conduct a robust analysis of the costs of implementing and scaling the initiative within the existing education system had not been collected. Another barrier was capacity limitations from both government and nongovernment stakeholders in terms of how to conduct cost analysis to inform scaling decisions. Finally, there was hesitancy around sharing cost data with outside partners. However, there were also some promising examples of using costing to inform scaling.

- In Côte d’Ivoire, the RTSL hired an external costing expert to gather data on the costs of delivering the initiative and to build projections for several scaling scenarios. Comparing the costs of these scenarios helped key stakeholders identify what scaling scope and timeline would be most feasible given available financial and human resources. Once an optimal scenario was selected, its costs were compared to existing Ministry of Education expenditures, and the analysis informed the decision to identify adaptations to test for reducing costs of the training model.

While identifying and securing long-term funding was a recurring (and unsurprising) challenge, the RTSL cases did offer rich examples of innovative middle-term financing that leveraged unique partnership structures. These innovative funding partnerships removed pressures from short-term funding cycles and provided independent resources to support ongoing research and adaptation, while working to align the incentives of disparate actors.

- For example, in Jordan, implementing, adapting, and scaling the financial education program was financed by the Central Bank of Jordan and the commercial banks (as well key philanthropic partners) who agreed to contribute a portion of their local annual profits.

- In Côte d’Ivoire, the Transforming Education in Cocoa Communities initiative (TRECC) was collaboratively financed by three philanthropic organizations and the cocoa industry. The philanthropic organizations supported the majority of costs of piloting a suite of innovations and secured agreements from cocoa and chocolate companies to pay the remainder, alongside making commitments to increase financing if the government moved any of the pilots to a scaling phase. The Ministry of National Education also provided in-kind resources by delivering the initiative in public schools through existing teachers.

- In Botswana, Youth Impact identified ways to leverage existing but underutilized resources already present in the system—namely a cadre of youth participants in the National Service Program, whose work in schools was already supported by the Ministry of Youth budget— to deliver the Teaching at the Right Level program in public schools.

These are just a few of the real-life examples and lessons that have emerged from the past five years of scaling lab research. If you are interested in learning more about institutional-level lessons related to evolving roles and non-linear planning, individual level lessons related to cultivating champions and treating educators as scaling partners, or reflections on the RTSL model itself, you can read the full report here.

The report is accompanied by targeted recommendation briefs for government decisionmakers, education implementers, researchers, and donor organizations. We would love to hear your thoughts questions, feedback – please reach out to the Millions Learning team.