Executive Summary

In 2014, the African Development Bank (AfDB) approved a new strategy for addressing fragility and building resilience in Africa that updated its earlier 2008 strategy for enhanced engagement in fragile states. Under its new approach, the Bank recognizes that there is no hope of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in Africa without successfully addressing fragility and building resilience in the continent.

Making the AfDB fit-for-purpose to scale up its impact in addressing fragility and building resilience at a national and regional level, affecting millions rather than thousands of people, is therefore imperative for the coming years. Underlying this is the expectation that AfDB will become more effective in fragile situations and that the fiscal situation of many shareholders will require it to do more with those resources available to it.

As an aggregate trend, the Bank’s commitments to so-called fragile states have risen

further and faster than in non-fragile states since 1999, and a combination of the Bank’s regular and dedicated instruments has allowed it to respond flexibly to diverse and changing needs, a key strength in fragile environments. However, a number of evaluations

have found that AfDB had not yet systematically devoted sufficient attention or capacity to key building blocks for successful scaling-up, such as analysis of country context, establishment of partnerships with non-state and international partners and establishment of systems to evaluate results and feed back lessons learnt into future programming. The efficiency of its administrative procedures, human resource management and approach to decentralisation also need strengthening if it is to engage effectively in fragile situations.

We see scaling-up as increasing the results from all AfDB’s activities in a particular country and the region to which it belongs. This is not the same as increasing AfDB financing, although more operational involvement, including finance mobilised by AfDB, may be

needed to scale up. The process of scaling-up is dynamic and takes place across time, as ideas get transformed into pilot projects, and the concept of reaching scale is refined as results from implementation come in. Such knowledge arising from practice being fed back into the full-scale rollout of the programme is inherent to scaling-up.

Our review of the literature suggests certain pathways and design features are essential for successful scaling-up of programmes. Designers need to have clarity about how scaling-up is to be achieved, through expanding or replicating a successful pilot or

through creating policies and incentives for independent actors to implement activities that reach scale. Sound design of pilots is critical for translating ideas into action. Partners need to invest in institutional development to build the organisational capacity and leadership necessary to go to scale. They also need to learn continuously in real time, adjusting pilot and programme design in the cold reality of results and generating information needed for decisions on scaling-up; this should be at the heart of a scaling up programme. Finally, the environment in which scaling-up will take place needs to be prepared and nurtured.

We propose that successful scaling-up by AfDB will require a strengthened response when favourable conditions emerge within agencies and sectors in its partner countries. Successful scaling-up will require partners to take the lead in designing, implementing

and evaluating programmes and projects that are capable of being scaled up; AfDB staff to have the knowledge and incentives to facilitate this scaling-up and to mobilise resources to support it; the Bank to have policies and instruments geared to supporting

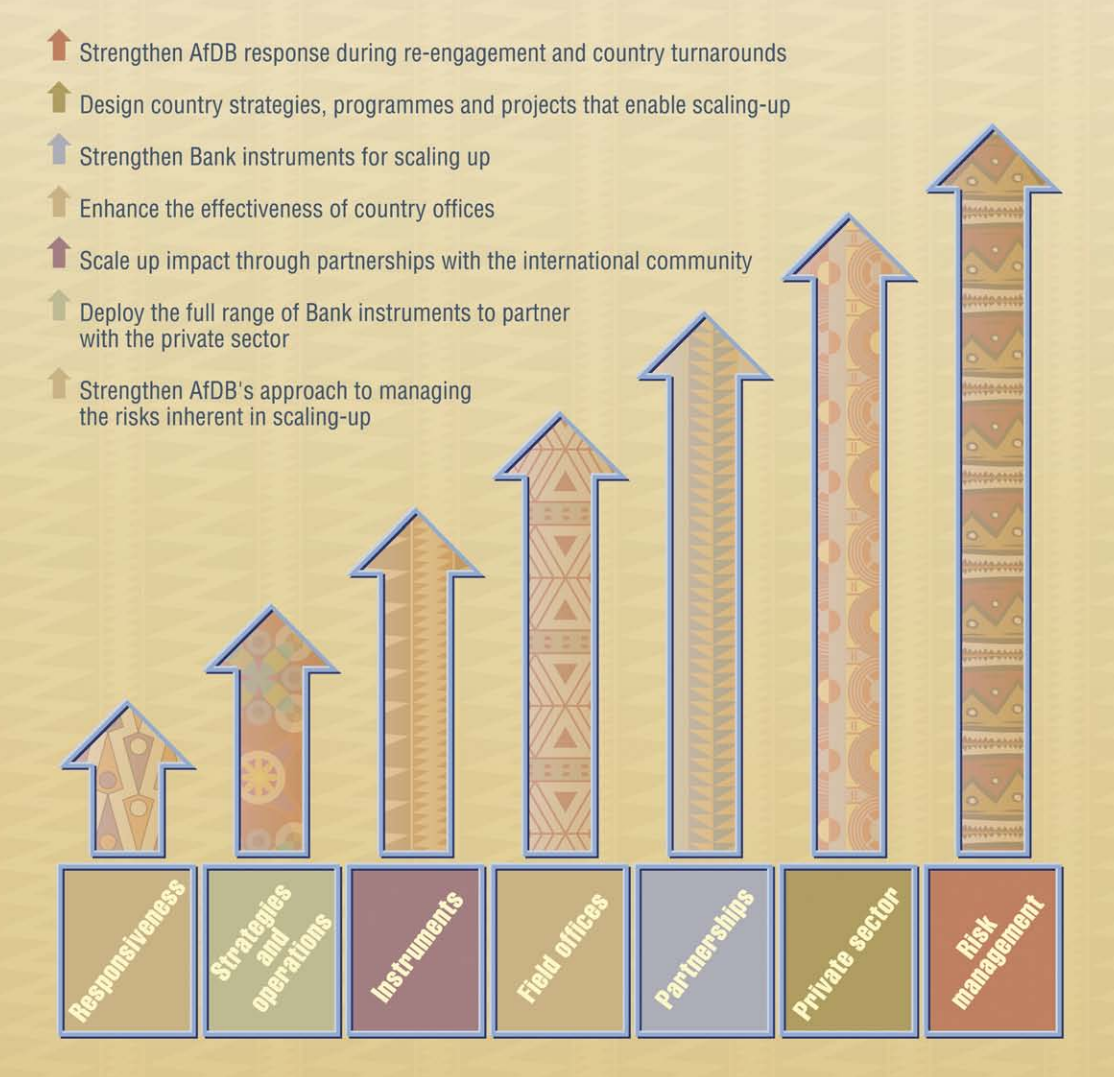

scaling-up; and the Bank to convene and forge partnerships with local and foreign actors that support well-coordinated assistance to produce results on a large scale. While the design of AfDB policies and instruments can constrain scaling-up, the Bank’s capacity can also be a binding constraint; realising potential for scaling-up requires having the right staff in field offices, with managers and staff fully aware of how the Bank can apply the policies and resources at its disposal to achieve large-scale results in fragile situations. This report proposes that AfDB adopt an approach along seven lines in order to enhance its effectiveness for scaling-up:

1 Strengthen its response during re-engagement and country turnarounds.

While AfDB seldom disengages completely with a country, it could respond more

rapidly and flexibly to positive changes in fragile situations. Key elements of a

strengthened response include systematically preparing watching briefs or

Country Dialogue Notes for countries where AfDB is not active; adopting a faster

and more flexible approach for securing Board approval for re-engagement;

addressing or containing constraints to re-engagement owing to arrears and

AfDB membership; and identifying a range of viable options for financing rapid

response. The Transition Support Department (ORTS) should be also be

encouraged to provide surge capacity during these periods; deploying staff

rapidly, including to field offices, allows for programmes to reach scale quickly

in turnaround countries.

2 Design country strategies, programmes and projects that enable scaling up.

Country strategies should be sufficiently flexible to be able to respond quickly

to new opportunities that arise. This will require changing the requirements of

the Interim Strategy Paper to enable greater simplicity and flexibility, or seeking

Board approval through other instruments, such as the Country Brief or Country

Dialogue Note, for preparing initial operations, including financing, and for

strengthening the field office. Country programmes should be designed from

the outset to reach scale and contain monitoring indicators related to peace and

state building as well as development. Support to institution building should be

organised around solving country problems rather than transferring ‘best’ practice.

Projects should be kept simple so they do not overwhelm implementing

organisations, have local legitimacy/ownership and have clarity about institutional

arrangements and the underlying theory of change (including any policy drivers

of success and financial arrangements for scale-up and operation). Selectivity

should be based on the competency and leadership of implementing agencies.

ORTS should produce guidelines for staff on how to design programmes and

projects that can reach scale.1

3 Strengthen its instruments for scaling up: make more use of the potential of the Transition Support Facility (TSF) to attract additional finance for scaling; give the TSF more flexibility to allocate funds for scaling-up through retaining a portion of funds not allocated to countries and allowing reallocations between countries; and develop new instruments (or modify existing ones) to provide additional

financing for scaling up operations, including giving consideration to a results based financing instrument and a rapid response lending instrument for turnaround situations.

4 Enhance the effectiveness of field offices to manage the scaling-up of operations and engage effectively with the government and other partners through clarifying the functions of resident representatives and country programme officers to lead the strategic and operational aspects of the office, respectively; ensure field offices have access to high-quality sector advice by leveraging the role of

the regional offices; improve staff incentives to work in fragile situations; and take into account the higher costs associated with operating in fragile situations in budgets for field offices.

5 Scale up impact through partnerships with the international community.

AfDB should consider operating in partnership with other development partners as its default in fragile situations, seeking opportunities to develop joint country analysis and programme development wherever possible, as well as knowledge sharing based on results. It should also explore innovative ways in which it could co-finance interventions with other donor partners, and engage in a more strategic

and systematic way with pooled funding mechanisms, which are increasingly being used as a major instrument for partnership in fragile situations.

6 Deploy the full range of Bank instruments to partner with the private sector.

Scaling-up the impact of the private sector on development, employment and government revenues will involve increased support for private investment generally and an expansion of public–private partnerships, especially in infrastructure. Reforms to the business climate are likely to take place slowly, and private investment is also inhibited by failures in other markets and the supply of skilled labour. The challenges of private investment in fragile situations will require the Bank to deploy the full range of Bank instruments in well-targeted and well-coordinated interventions involving sovereign and non-sovereign debt and guarantees that also address complementary investments that go beyond the private sector, for example in education, infrastructure, secure serviced land.

Selectivity in setting priorities for the Bank’s country-level private sector development work should be based on potential scale and impact. Capacity building for private firms in critical sectors like construction and building materials, and ensuring funding for preparation of bankable projects, should not be neglected. The Bank has a comparative advantage in private sector development

in fragile situations and now has a good range of financing and risk management instruments. Scaling-up will require a consistent approach in country and sector strategies, as well as broadly strengthening its own capacity through investment in staff training, developing a pipeline of operations, management commitment of staff and resources and setting targets for a more robust engagement in private sector engagement in fragile situations.

7 Strengthen its approach to managing the risks inherent in scaling-up. While concentrating resources on a few programmes that are scaled up might expose the Bank to greater fiduciary and reputational risks and risk of programme failure, these risks could actually be lower than the sum of the risks associated with many small projects. Scaled-up programmes are associated with investment in institutions and the testing of approaches, systems and institutions through pilots that a more fragmented programme may lack. Risks associated with scalingup can be mitigated through active risk management and sound programme design. Country strategies need to set out how risks will be managed, including the trade-offs between fiduciary risks and programmatic and contextual risks. In a fragile situation, risk analysis needs to be informed by a deep understanding of the political economy of the country and its evolving political settlement.

1 A tactical issue for the Bank is whether to develop guidelines for scaling-up in all countries, or to issue interim guidelines for scaling up in fragile situations. We suggest it might be easier to pilot guidelines for fragile situations and

then extend them more generally.