Introduction

The international development community is increasingly paying attention to the need to sustainably scale development impact.[1] One indicator of this growing interest is the rapid increase in the membership of the Scaling Community of Practice (CoP). Moreover, there are indications that development funders individually and jointly are focusing more on scaling development impact than has been the case in the past.[2] And surveys by the CoP of its membership and the Agence Française de Développement of its local partners show a clear interest in the wider development community in the scaling agenda. The reason for this growing interest is clear: The international community’s ambitious development and climate goals (the SDGs and the Paris Climate Targets) can only be reached if we focus not only on how we can increase the amount of development and climate finance in a world of increasingly constrained public budgets but, as importantly, on how we ensure the available finance is deployed for sustainable impact at optimal scale.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE

Many funders and recipients realize that traditional one-off project-based approaches are increasingly untenable in the face of escalating needs and scarce resources. However, we do not know how widespread nor how deep this scaling focus is among funder organizations.[3] In particular, we do not know whether the focus on scaling is limited to lofty ambitions in mission statements and public announcements, or whether it also is increasingly embedded and effectively deployed in operational practice. Nor do we know what lessons can be learned from efforts to mainstream the scaling agenda in particular development funding organizations. The mainstreaming study described in this note and of the learning process it supports is being commissioned by the Scaling Community of Practice (CoP) to inform its members and the wider development community of the current state of support for scaling in a broad range of development funding agencies, to draw lessons for future efforts to mainstream the scaling agenda in the development funding community, and to promote more effective funder support for scaling by stakeholders in developing countries.

By “mainstreaming” we understand the systematic, organization-wide incorporation of support for sustainable outcomes at scale in the mission and strategy statements of the funding organizations; in their operational policies and guidelines, financing instruments, allocation decisions and time horizons; in their administrative budget, staffing practices and incentives; and in their monitoring and evaluation practices. This requires a fundamental change away from the common mindset and presumption that, as long as a project is a “good” project, subsequent replication or scaling will happen spontaneously or is someone else’s responsibility, and that the enabling conditions required for successful scaling will somehow materialize.[4]

A key question to be addressed in this context is to what extent and how funder agencies are willing and able to increase the agency and capacity of recipient countries and organizations for scaling, and with it the devolution of resources and resource management to them, because these are key determinants of successful scaling. Progress in this respect likely requires a fundamental shift in funder approaches to how they interact with their national counterparts and stakeholders.

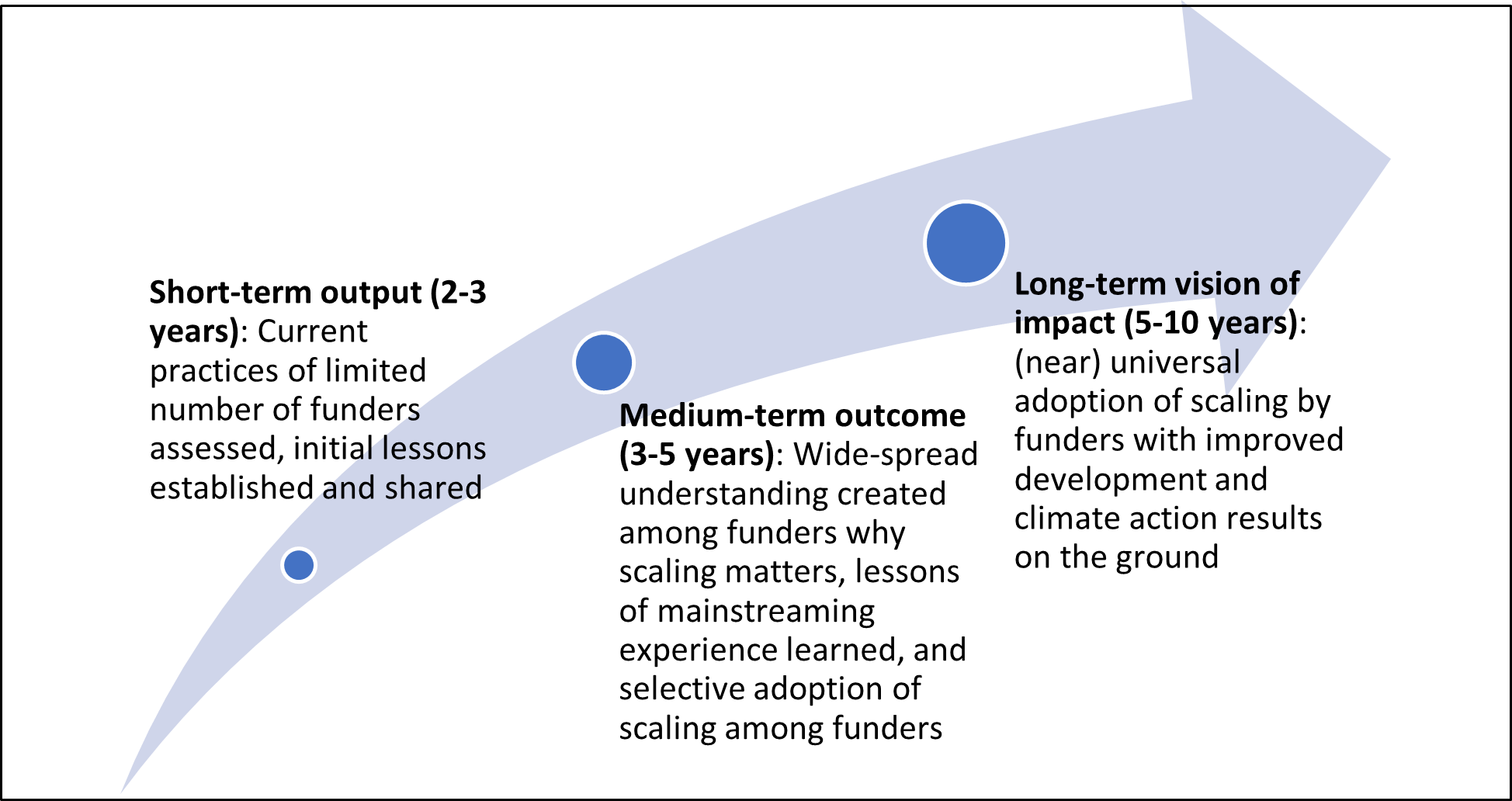

The vision of the work to be undertaken is to bring about widespread change in funder practices. But achieving this vision is clearly a long-term proposition and indeed is itself a scaling task, since it means achieving a scale goal of widespread adoption of good practices for support of scaling among the large community of funder organizations. The potential scaling pathway is shown in Figure 1 below, linking the vision of long-term impact with medium-term outcomes and short-term outputs.

Figure 1. Indicative scaling pathway for the proposed work on mainstreaming

The study will involve a process of in-depth engagement with funders and outreach to their recipient partners in developing countries, complemented by ongoing outreach in the form of webinars to the Community of Practice and beyond. It is hoped that this process will not only result in the documentation of current practices and lessons, but that it will also lead to changes as needed in the practices of the funders participating, and in the attention to scaling in the wider funder and development community.

This concept note presents the contours of the initial phase of work that could extend for 2-3 years and produce the short-term outputs identified in Figure 1. The proposed work will be focused on a limited number of funder agencies, on establishing current practices and lessons, on building the preconditions for subsequent phases of work, and on sharing the findings with the CoP and community of funding organizations. Due to present resource constraints, this first phase of work is again subdivided into two stages – an initial one-year program that is presented in detail as a proposal for approval by the Executive Committee of the Scaling Community of Practice, with the second stage to be prepared and, as needed, adapted to complete the work during the first phase.

Antecedents

In preparation for this review, the Scaling Community of Practice (CoP) commissioned a background paper by Richard Kohl (2022) to:

- determine if a larger mainstreaming study makes sense, and, if so, inform a decision about its intended audience and primary purpose;

- confirm or refute the assumption that action by funders to support scaling and to mainstream a focus on scale within their policies and practices remain limited;

- do a high-level assessment or landscape analysis of where mainstreaming is happening, the form(s) it is taking, and the characteristics, drivers and obstacles to mainstreaming efforts;

- develop tentative hypotheses and topics that could be addressed in greater detail in a full study; and

- make recommendations as to the methodology such a study should take and the organizations that would serve as good case studies.

Based on a review of the literature, expert interviews and a survey of CoP members, the author of the background paper concluded as follows:

- The CoP should pursue a study of mainstreaming of scaling in donor organization and the CoP is well placed to pursue it. The purpose of such a study should be to collect evidence on, and lessons from, the current state of practice and to provide the basis for the CoP to promote change in funder practices towards more mainstreaming of scaling.

- There is currently a dearth of analytical and case study information available in the literature (with the exception of some work carried out mostly under the auspices of Brookings).

- From the preliminary evidence available, scaling is increasingly being integrated into funders’ high-level statements of mission and strategy, but is generally not systematically pursued in funders’ operational practices; vertical funds appear to be an exception in their more systematic pursuit of impact at scale.

- A main obstacle is funders’ traditional focus on a one-off project approach, rather than a focus on supporting a longer-term scaling pathway.

- A further study of mainstreaming scaling in donor organizations would best focus on whether and how scaling is integrated into funding practices, complemented by case studies of how this is implemented and to what effect. Rigorous assessment of the impact of mainstreaming scaling on development outcomes was thought to be unrealistic during the initial phase of the research, except possibly in selected project or program case studies.

- Principal questions worth pursuing include: (i) what are the drivers of mainstreaming, and how to get senior management to back and lead initiatives; (ii) the role of organizational mandates, incentives, capacity and resources in driving and implementing mainstreaming; (iii) the role of middle management and staff in supporting or opposing mainstreaming, and how to address it; (iv) bureaucratic and administrative rules, regulations, procedures etc. as obstacles (or facilitators) of mainstreaming; (v) the role of partnerships, and how to address the mixed historical record of donor collaboration to promote scaling; (vi) the additional activities, effort and costs that a greater focus on mainstreaming might require; and (vii) the risk of higher failure rates in individual projects or grants, and how those could be addressed, such as investing more resources in a fewer efforts, a portfolio approach, using a funnel or stage gate approach, or some combination thereof.

- Any such study would best be carried out in cooperation with funding agencies in the form of joint learning efforts, rather than as external evaluations.

- Vertical funds, official bilateral funders, and large foundations were identified as the best initial focus for the research since the large multilateral organizations were likely to be complex to assess and the smaller funders (innovation and challenge funds, smaller foundations, and international NGOs) were likely too small and too diverse for an effective review.

Building on these findings, this concept note further explores the rationale for the proposed research, lays out a 2-3 year program of work to explore and promote the idea of mainstreaming of scaling among development funders, and closes with a specific proposal for the first stage (and first year) of the study.

Why worry about funders’ approach to scaling?

While funders do not directly implement development programs, projects or policy changes, they often influence program goals, results and deliverables, approve the designs and workplans, and require specific M&E and reporting indicators and systems from the organizations or projects that they fund. Therefore, funders carry a special responsibility to ensure that their funding practices support rather than impede scaling by the recipients of their funds.[5]

Unfortunately, most donors do not explicitly focus on funding sustainable scaling. In fact, many traditional funder practices have tended to inadvertently undermine scaling efforts:[6]

- Funders typically support time-bound projects, which for most donors (excepting the MDBs and a few large bilateral donors and foundations) tend to be small (and getting smaller), which are one-off, limited in time (2-4 years), and focused on delivering impacts for the project beneficiaries during the project’s duration, but not beyond.

- Funders have not focused enough on aligning with national priorities and ownership and on supporting and building local capacity for scaling, i.e., the capacity of national actors to analyze their development challenges, develop suitable responses, and prepare, implement and evaluate projects for sustainable impact at scale.

- The “aid architecture” is heavily fragmented, with many funders operating in the same development space (geography, sector, thematic area, etc.) in any particular country, with poor coordination, limited partnerships, different and even conflicting approaches, etc.[7]

- Funders focus on supporting “innovation”, reinforced in recent years by the popularity of innovation labs, challenge funds, accelerators, and hackathons, but fail to pursue effectively the scaling of promising innovations.[8]

- Project monitoring and ex-post evaluations focus on timely delivery against project plans, on the proper disbursement of funds, and on the achievement of narrow results targets, not on whether the project is putting in place the conditions for sustainability and scaling of project impact beyond project end.[9]

These practices are particularly unfortunate, since funders could and should in fact serve as important champions, facilitators, intermediaries and providers of incentives for the scaling process by implementing agencies and actors, but rarely do so.[10] Therefore, it will be important for funder agencies to support scaling in a more systematic and effective manner than they done hitherto.

Approach to assess mainstreaming of scaling in funder organizations

As noted in the introduction, the purpose of an assessment of the current mainstreaming practice is to inform the members of the CoP and the wider development community of the current state of support for scaling in a broad range of development funding agencies, draw lessons for future efforts to mainstream the scaling agenda in the development funding community, help participating funder organizations to adapt their operational practices, and provide the basis for a promotion of good mainstreaming practices by the CoP. The audience will be (i) the CoP members, (ii) the boards, managers and staff of funding agencies, and (iii) the recipients of donor financing, who are affected by the way funders approach the scaling agenda.

Rather than focusing the research on a narrow set of funder organizations, as recommended by the author of the initial scoping study summarized above, the proposal for the first phase of work is deliberately broad in coverage so as to develop a comprehensive understanding of issues, challenges and opportunities for mainstreaming. Depending on the results, the focus may be narrowed in subsequent phases.

The assessment of scaling practices and lessons will be carried out at four levels. The first level is to look at specific funder agencies and their practices. The second level explores funder engagement in support or hinderance of scaling as seen by recipients. The third level explores what can be done at a system-wide level by the funder community (or subset thereof) to monitor and incentivize the mainstreaming of scaling. A fourth level of the study will develop a mainstreaming scan tool for measuring and tracking the degree to which the scaling agenda has been mainstreamed into funders’ operational practices. At a fifth level the results of the study will be widely disseminated on an ongoing basis so as to promote a more effective support of scaling by the funder community. The study will consist of five components, one each corresponding to these five levels of analysis.

Program of work

Component 1. Agency level: scaling reviews for individual development funders

Two approaches will be used to collect information and garner insight into the scaling activities of individual development funding agencies: (a) “inside-out”, i.e., assisting agencies in doing their own scaling reviews; and (b) “outside-in,” i.e., collecting evidence on the scaling performance of agencies from the outside. Both approaches will be pursued, but to varying degrees.

Component 1.a. Inside-out analysis

A principal element of the study will be to identify funding agencies that are interested in exploring their own scaling practices and pursuing a mainstreaming agenda. The study will work with these agencies to help them define a suitable mainstreaming approach tailored to the specific characteristics and needs of the agency. For smaller agencies, this will likely involve an agency-wide assessment. For large agencies for which a comprehensive review may be difficult to carry out or for which it may be more difficult to obtain senior management buy-in, an approach focusing on selected organizational units or programs may be more appropriate. For example, for the World Bank it might be appropriate to review the experience of social inclusion programs,[11] or support for the scaling of social enterprises, or of programs in fragile states.[12] For USAID, the scaling approach pursued under the auspices of the Feed the Future Program would be a good candidate.

Main questions to be addressed for each participating funder

For the selected funders (see list of potential candidates below), this part of the review will ideally seek to obtain answers to the following questions:

Is scaling a central part of the organization’s mission statement and have the visible support of the organization’s leadership?

Does the funder have a systematic approach to the support of scaling that is appropriate for the organization and its mission, with special attention to current organizational practices in six areas:

- organizational strategy;

- operational business models and financing instruments;

- internal policies, guidelines, and management processes;

- approach to partnerships, coordination and networking;

- staff and management incentives; and

- monitoring and evaluation of funded projects/programs?

How does the organization define scaling and does it include a consideration of the devolution of resources and responsibility to recipients?

Does the funder’s project model incorporate a systematic focus on sustainable scaling beyond project end and on the devolution of resources and responsibilities to recipients?

If the organization is aiming at mainstreaming, what is it doing to:

- strengthen enabling factors (leadership from the top, champions, support from the authorizing environment such as Boards and replenishments;

- strengthening the organizational practices identifies under ii. above);

- reducing barriers (including bureaucratic inertia, staff overload, and multiplicity of initiatives);

- assuring appropriate budget, staffing and training support); and

- monitoring and evaluating progress with the mainstreaming process?

The limited experience to date with efforts by funders to mainstream scaling into the funding and operational approaches indicates that the process is not linear nor is there only one way to do it. The study will therefore endeavor to identify different mainstreaming pathways and dynamics, assess common and unique challenges encountered, and compare and contrast solutions that may serve as the basis for best practices. For example, one typical dynamic appears to be that periods of progress with mainstreaming are followed by periods of reversal. The review will aim to assess whether this is correct and, if so, what are the factors explaining this pattern and what can be done to help prevent reversals.

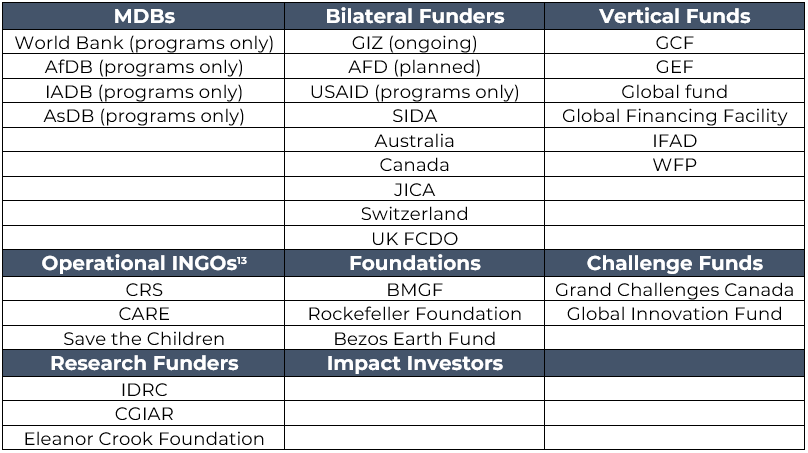

Potential funding agencies to be involved in this study

Below is a preliminary list of funder agencies that in principle could be approached for possible inclusion in this review, grouped by type of agency. Actual selection will depend on a number of factors, including (a) resources and time available; (b) willingness of the agencies to cooperate in the evidence gathering process; and (c) focus of the review – some categories of donors are more relevant than others for various purposes.

[1] Many INGOs are both funders or implementers. To the extent they fund other implementing entities, they can be treated as funders, but to the extent their local offices deliver development services (e.g., training and extension services to farmers) directly, hey are implementers, not funders.

As noted above, the exploratory background review recommended that the mainstreaming study initially focus on vertical funds and bilateral donors. This would ensure some minimum of comparability across funders. The approach recommended here is more comprehensive and opportunistic, working with funders willing to engage in the study on the terms envisaged. While this may limit comparability across funders, it will demonstrate how mainstreaming applies for different types of funders and hopefully produce useful lessons of interest and utility for a wider range of funders.

One type of funder will not be included in the first phase of the study is impact investors. As pointed out in the background review, although impact investors represent an important potential source of funding for scaling innovative development and climate interventions, they represent a very different class of funders than the other categories of funders to be covered under this study. Their approach could be usefully explored in later phases.

Recognizing differences across funders

Funders differ in the way they can support scaling. Some will want and need to focus on supporting government-led scaling, while others focus on private sector led scaling, and yet others on hybrid pathways. Smaller funders can expect to support the testing of innovations, the early stages of scaling, and/or scaling with more limited scope or geographic impact, while also recognizing that systemic enabling factors or constraints will often be beyond their recipients’ scope of influence or restricted to localized efforts. Larger funders may appropriately focus on supporting scaling at a national or even international scale and on catalyzing systemic changes that will achieve transformational impact at national scale through support for national policy reform and capacity building. The study will endeavor to reflect these differences among funders and differentiate lessons accordingly. One of the interesting questions to be explores is to what extent different types of funders can partner across the scaling pathway in supporting a “transmission belt” of scaling, where smaller funders support the early stages and more localized dimensions of a scaling pathway, while the larger funders support scaling at a later stage with a national scale goal.

Modalities of engagement with participating funding agencies

A principal objective of this “inside-out” exercise will be learning by the agency for its own purposes, and participating agencies would be expected to contribute their own resources (staff and management time) to carry out much of the work involved in reviewing approaches and practices, with the CoP mainstreaming expert team providing advice and comparative insight from other agencies and supporting the production of agency-specific reports. However, the results of this work by and for each agency would be expected to be shared with the study team and incorporated into analytical reports of the mainstreaming experience for the CoP and donor community as a whole.

Component 1.b. Outside-in analysis

As noted, Kohl’s review concluded that an inside-out approach is likely more productive. Nonetheless, there is evidence readily available on outside-in evaluations of funder scaling practices, which the study will access and whose insights it will add to the overall evidence. This includes, first, available independent evaluations of scaling for GIZ, IDRC, IFAD, GEF and GCF. Other such evaluations will be researched, including for the Global Fund, for GAVI, CREWS, and for other vertical funds, for which evaluations are available.

Second, even though traditional project evaluations generally do not provide much insight into scaling, sector-wide evaluations of MDB programs (e.g., for health, education, etc.) can be usefully scoured for evidence that scaling was supported or not, and if so, in what way and with what success. This was demonstrated by Linn (2011, op.cit.) and, building on this experience, more recent sector evaluations can be consulted.

A third source of outside-in analysis can be a survey of the CoP membership. An experimental survey was conducted by Kohl (2022, op.cit.) for his exploratory assessment. Learning from that experience, an amended survey instrument will be developed, and with more intensive outreach to the membership it should be possible to collect information from a larger sample of respondents.

The study does not expect to carry out external scaling evaluations of or for individual agencies.

Component 2. Recipient level: the recipient perspective of how donor processes affect scaling

The recipient perspective on whether and how donor processes and approaches affect recipients’ potential scaling activity is an important complement to the donors’ perspectives. While there is a lot of impressionistic insight that indicates that recipients feel funder support for scaling is lacking and that common donor practices discourage scaling by recipients, we are aware of no systematic substantiation of this perception.[14] Gathering more comprehensive and systematic information on recipient experience will an essential pillar of this study.

The range of recipients that should be considered is, in principle, very wide. It includes governments and their implementing agencies at national and local level, private firms, as well as social enterprises, NGOs and research organizations.

The easiest way to obtain insight into recipients’ perspectives on donor activities is to survey recipient members of the CoP. This could either be a free-standing survey or be a stratified component of a more general survey. Depending on the response, one might obtain significant results for the entire group of recipients, but probably not for all the various subgroups of recipients mentioned above.

To gain more in-depth information, other research tools could be used, most likely pursuing different recipient groups separately. For research institutions and researchers, the findings of the IDRC-inspired scalingXchange and its Southern members’ call to donors for action is available and could perhaps be expanded, with support from IDRC, CIMMYT and ECD, who might be able to assist in surveying their recipients.[15] For social enterprises, IMAGO could be asked to run survey of its members and clients. The Millions Lives Collective is another platform for recipients which might be willing to organize a survey of members. For NGOs, it would be valuable to collaborate with Southern NGO associations and consortia to organize a survey, perhaps with the assistance of northern NGOs, such as the Heinrich Böll Foundation, which has good contacts with Southern NGOs. For governments and private firms, a case-study approach would be the most effective way of gathering information, but this would require significant resources. Finally, in working with specific donor partners, we would propose to investigate the feasibility of organizing surveys of recipients’ and implementing partners’ perspectives on the donors’ support (or lack thereof) for sustainable scaling.

Component 3. Systemic level: development effectiveness assessments and evaluations

Currently, there are various system-wide efforts to assess the development effectiveness of official donor agencies.[16] They include the peer reviews of bilateral agencies’ programs under the auspices of the OECD-DAC,[17] the review of multilateral finance agencies’ performance under MOPAN,[18] and the reviews of QODA, which rate the development effectiveness of selected multilateral and bilateral official development agencies, carried out by the Center for Global Development (CGD).[19] In addition, some bilateral donors carry out occasional reviews of the effectiveness of selected multilateral agencies[20]. In principle, these effectiveness assessments of official development funding agencies represent excellent opportunities to obtain system-wide comparable information on whether or not official funding agencies support scaling through their financing activities. However, from preliminary reviews it appears that the assessment criteria and approaches used in these studies do not generally include a systematic focus on sustainable scaling.

In addition to these agency-wide assessments, there are evaluations of individual officially-funded projects and programs carried out by the agencies’ evaluation offices (generally independent units reporting the agencies’ board rather than to management). 25 of these evaluation offices cooperate under the umbrella of the Global Evaluation Initiative (GEI).[21] So far, it appears that standard evaluation criteria and approaches employed by the evaluation units do not focus sufficiently, if at all, on scaling. Working with this group could potentially drive the inclusion of scaling into the broader development effectiveness evaluation approaches throughout the multilateral and bilateral development finance system.

Currently, the CoP has good contacts with OECD-DAC and will be aiming to help (a) develop scaling principles for DAC donors, (b) review and adapt the DAC peer review approach to include a scaling focus, and (c) work with the OECD-DAC Network on Development Evaluation to explore how best to adapt or complement the DAC project evaluation criteria to reflect scaling. Beyond this, resources permitting, contacts can be established with the MOPAN and QUODA teams, as well as with the Global Evaluation Initiative, with a view to get them to explore how best to incorporate scaling considerations into the assessment criteria and approaches. They might also be willing to carry out e-mail surveys of their members/clients on key aspects of their members’/clients’ scaling practices.

In this work, use will be made of the development of the “mainstreaming tracker” which is to be developed as part of the overall mainstreaming study (see Component 4 below). In all cases, the intention is to work with the teams in charge of the development effectiveness assessments, rather than carry out purely external reviews and critiques of the agencies’ approaches.

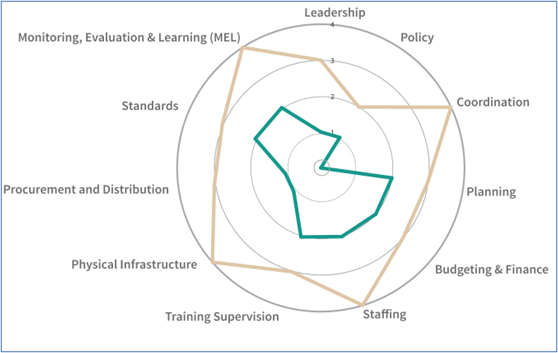

Component 4. Tools for tracking mainstreaming

To complement and underpin the work in the previous components, the review will aim to develop a standard set of practical criteria and metrics that can be used to assess the degree of mainstreaming of support for scaling in funder organizations and provide guidance on where additional action is needed. The initial set of criteria would be the ones presented above under Component 1.a above. With exploratory application in the process of the study, these initial criteria could be validated or revised. This will form the basis for developing a “mainstreaming scan” tool similar to the “institutionalization tracker” that was developed by MSI (see Figure 2 below) and the scaling assessment tool developed by Begovic, Linn and Vrbenski (2017) at Brookings for UNDP. The extent of effort made by the funder organization to devolve resources and resource management authority to the recipient partners would be added to the criteria. The criteria could also be used to inform the criteria for the systemic assessments of donor effectiveness considered in Component 3 above.

Figure 2. MSI Institutionalization Tracker

Source: MSI, Scaling up: From vision to large-scale change –

Source: MSI, Scaling up: From vision to large-scale change –

Tools for Practitioners Second Edition, Second edition, 2021

Component 5: Outreach and promotion of mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations

The study team and, to the extent possible, its funder partners will engage in outreach for the promotion of mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations by organizing webinars, participating in conferences, publishing blogs and posting on social media.

Outputs, impacts, and sequencing of the study

Outputs

The study will result in multiple types of outputs:

1. Published documents

Each component of the above study agenda will result in working papers and blogs that summarize the findings, lessons and implications of the analysis. These working papers and blogs will be vetted, edited and posted on the CoP website.

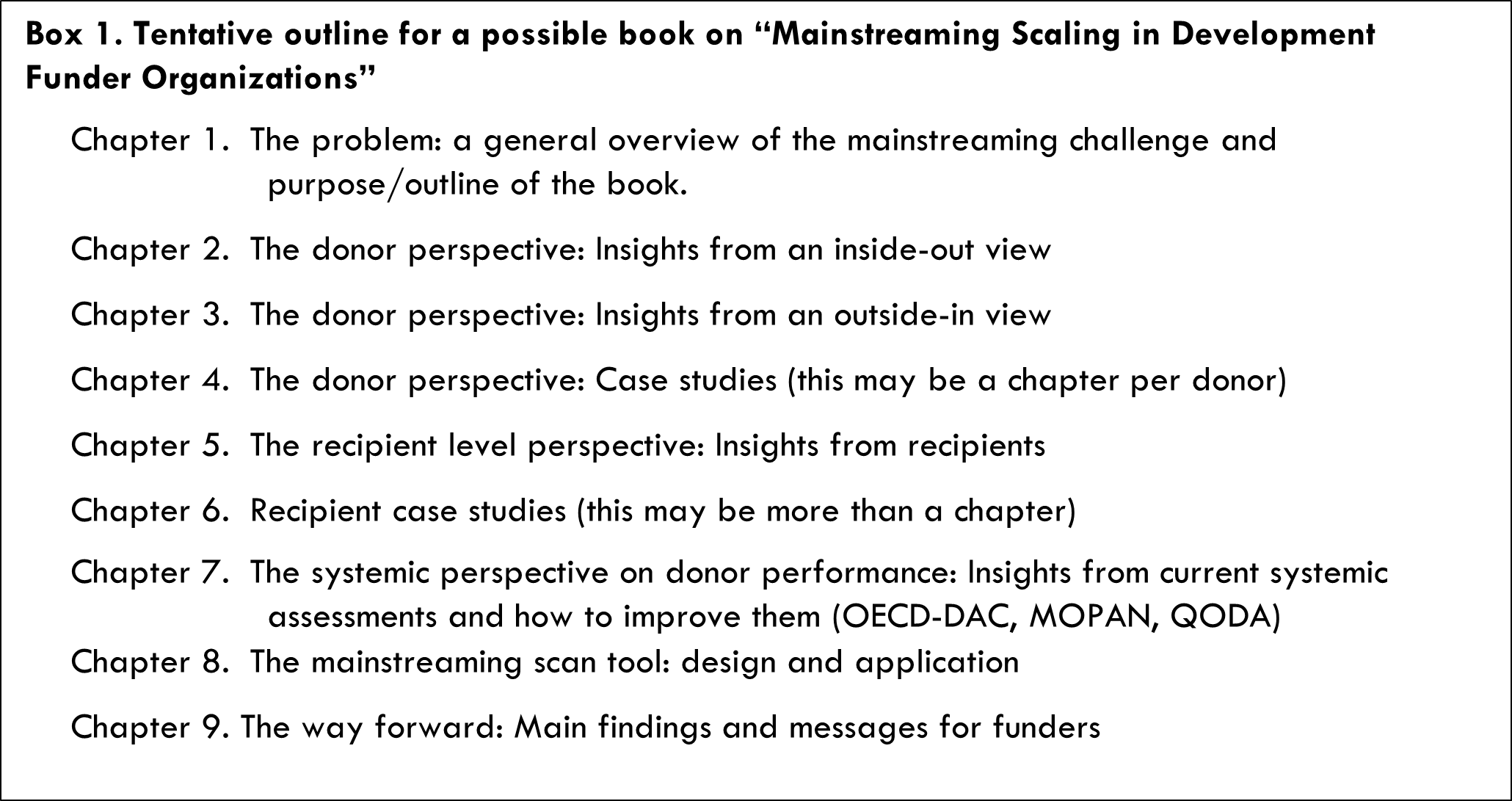

If the eventual collection of working papers and blogs warrants a book publication, it would have a table of contents such as that shown in the box 1 below.

2. Webinars

As work progresses on the various components, webinars will be organized for the CoP to share preliminary results and insights for discussion and feedback. This is a critical component of the proposed work, since it will ensure maximum visibility for the study and engagement by CoP members, as well as offer a continuous feedback loop for the substantive work as it progresses.

3. Outreach and promotion of mainstreaming

Where the proposed work involves work in partnership with specific funders (and other relevant organizations, such as DAC, IDIA, MOPAN, etc.), presentations of the findings of the work for management and staff will be organized to ensure that the results of analysis feed back into the mainstreaming efforts of the organizations. In addition, outreach to the broader development and climate communities will be undertaken to support the mainstreaming of scaling.

Impacts

The expected impacts of the study include the following:

Components 1 and 4: 4-6 partner funding agencies have a better understanding of the need to mainstream scaling and are undertaking steps to mainstream scaling and monitoring progress, including by the use of the mainstreaming scaling scan developed by the study.

Component 2: Recipients in the Global South report increased support by funders for scaling and improved funding processes that support, rather than hinder scaling.

Component 3: Scaling criteria are included in systemic assessments of official development funder agencies and evaluation criteria (OECD-DAC peer reviews and evaluation criteria and OECD DAC has approved a set of scaling principles on behalf of its bilateral official funder members; MOPAN; QODA; etc.).

Component 5: There is increased awareness of the need for support for scaling and enhanced capacity for such support in the wider funder community.

The first phase of this work will not aim to assess the impact on ultimate beneficiaries of funder activity. This will be left for subsequent phases of the study.

Sequencing of the first phase of the study

Given financing and staff constraints, Phase 1 of the study will be sequenced in two stages:

Stage 1: initial exploratory research under the four components , expanding contacts with donors and raising additional resources for next stages

Stage 2: expanding and deepening of steps across the four components and compiling overall results, followed by active dissemination and promotion

Stage 1 is expected to take a year, Stage 2 another year-and-a-half.

Stage 1 will be carried out in partnership with Agence Française de Développement.

Concluding comment on the research approach of the study

The approach in this study is comprehensive in its coverage of issues, levels and approaches, and opportunistic in the selection of the funder organizations it will partner with. One consequence of this framing is sacrificing some of the depth that would have been the case for a study that was more focused on a small number of issues, levels and approaches and that worked with a more limited set of funders. The justification for the proposed approach is the exploratory nature of this study, where the payoff for any one of the specific components is uncertain, and the expectation is that a better understanding of the overall mainstreaming problem will result in a wider array of relevant lessons and greater impact on changing funder practices.

[1] Following Kohl and Linn (2021) we define scaling as a “a systematic process leading to sustainable impact affecting a large and increasing proportion of the relevant need.” This implies that funder organizations define what contribution they can expect to make not only in absolute terms but relative to portion of the need they expect to address. Note also that sustainability is incorporated in the definition of scaling as essential component (i.e., “sustainable outcomes) recognizing that scaling without sustainability means that impacts may be at scale, but transitory.

[2] Examples include IFAD, GIZ, AfDB, World Bank, AFD, OECD-DAC, members of IDIA, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Eleanor Crook Foundation, Save the Children, CRS – to name just a few.

[3] This concept note uses the terms “external development funders” and “donors” interchangeably.

[4] For an example of such “magical thinking” at the World Bank, see Linn (2019)

[5] Hartmann and Linn (2008). See also the video of a panel discussion during a Skoll-organized event on “Elephant in the Room: Funder/Government Power Dynamics” for some of the issues and challenges in the relationship between funders and recipients governments in the process of scaling.

[6] Linn (2011), Chapter 9

[7] Ibid; World Bank (2022)

[8] Kohl (2022), op.cit., notes that innovation and challenge funds are increasingly held to account for impact at scale without having the resources to support scaling effectively.

[9] See for example the OECD-DAC evaluation criteria.

[10] Linn (2011), op. cit.; Kohl (2022), op. cit. The Million Lives Collective, which is supported by the International Development Innovation Alliance (IDIA), an alliance of development funders, champions initiatives that reach scale. However, there appears to be no systematic link between the Collective and the funding by IDIA members to support further scaling.

[11] See https://www.peiglobal.org/state-of-economic-inclusion-report-2021 and the WB engagement on scaling social protection programs under the Partnership for Economic Inclusion (https://www.peiglobal.org).

[12] These two examples could be explored with the assistance of the co-chairs from the CoP’s social enterprise and fragile states working group).

[13] Many INGOs are both funders or implementers. To the extent they fund other implementing entities, they can be treated as funders, but to the extent their local offices deliver development services (e.g., training and extension services to farmers) directly, hey are implementers, not funders.

[14] IDRC’s scalingXchange has worked with IDRC grantees to collect their perspective on scaling support from donors; this has resulted in a call to action addressed to donors by the grantees.

[15] https://www.scalingxchange.org

[16] There are also some, albeit limited efforts to assess the effectiveness of charitable organizations, including CharityWatch (https://www.charitywatch.org), American Institute of Philanthropy, Charity Navigator and the Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance

[17] https://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/

[18] Multilateral Organization Performance Assessment Network https://www.mopanonline.org

[19] Quality of Official Development Assistance https://www.cgdev.org/blog/quoda-2021-aid-effectiveness-isnt-dead-yet

[20] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/raising-the-standard-the-multilateral-development-review-2016