Preface: A Short Guide for This Document

This report is an interim synthesis of findings from a two-year research initiative undertaken by the Scaling Community of Practice. It reports on preliminary results of the analysis after the first year for the purpose of stimulating discussion and feedback as part of the ongoing research. The initiative is expected to be completed by mid-2025.

The world faces great development and climate challenges which require actions that achieve sustained impact commensurate with the global scale of the problems. The pursuit of international development and climate interventions with sustained impact at scale in turn requires a shift from prioritizing innovations and the immediate outcomes of projects and programs to increasing the capacity to deliver long-term sustainable impact that addresses a significant portion of the global problem.

Section I of this paper argues that development and climate funder organizations play a key role in supporting the pursuit of sustainable impact at scale, but that in the past they have in general not focused adequately on the scaling agenda. However, recognizing that they need to increase their overall effectiveness and address the scale of global problems today, funders are now increasingly focusing on impact at scale. This report assesses how selected funders have mainstreamed scaling into their operational practice and what lessons can be learned from their experience. Mainstreaming scaling means systematically integrating scaling into organizational objectives, strategies, business models, operations, resource allocation, managerial and staff mindsets and incentives with a focus on impact and results, not disbursements and short-term outcomes achieved.

Based on twelve case studies, we assess in Section II the role of funders in supporting scaling and overall progress on mainstreaming scaling. Case studies were purposively selected to examine a wide range of funder organizations known to be conducting some mainstreaming to facilitate the development of lessons learned and recommendations. Following an “action research” approach, funder staff wrote or supported the writing of case studies. We find that individual funders support different stages in the pathway from innovation to sustained operation at scale and in principle could seamlessly support the scaling process. In practice, gaps in the support for scaling initiatives regularly occur for lack of coordination and hand-off from one funder to the next and the fact that large project funders who could integrate scaling into their projects often do not. We find that there has been progress with mainstreaming scaling, especially among smaller funders and those focused on innovation. Larger funders, and especially the bilateral and multilateral official funder organizations, still tend to be stuck in the one-off project mode and do not effectively cooperate with smaller and innovation funders to scale the latter’s successful initiatives.

Section III identifies the main enabling conditions that support mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations. We find that sustained efforts by senior leadership are the most important driver of success in mainstreaming scaling. Leaders who achieve the greatest progress in mainstreaming scaling spearhead a process of long-term systematic

organizational change in pursuit of mainstreaming. This includes establishing shared organization-wide concepts and definitions of scaling and an understanding of the organization’s role within the overall development community. To maximize the chances of success, mainstreaming requires sustained and cohesive action across the entire organization, including a clear statement of the long-term vision of sustainable impact at scale, and integration of a scaling approach into organizational mission statements, strategies, partnerships, incentives, operational policies and guidance documents. It requires organizational and staff incentives to be aligned with a well-resourced scaling agenda.

Section IV argues that mainstreaming also has to embody the principles of good scaling. This, starts with a focus on not just “transactional scaling” (i.e., more money for larger one-off projects and programs), but on “transformational scaling” (i.e., full attention to long-term scaling goals and potential pathways to achieve these goals that are aligned with local priorities and ownership and leverage local knowledge and solutions). The scaling approach also has to consider equity and inclusion, changes in policies and institutions (also referred to as “systems change”), localization, partnerships, and intermediaries to support funding continuity over the scaling pathway. Good scaling relies on monitoring and evaluation not only of impact but also of the enabling conditions needed to achieve sustainable impact at scale. Sections V and VI conclude the paper by drawing summary lessons respectively for individual funders and for the funder community at large. Readers who wish to take a shortcut to the main takeaways from this report are encouraged to review these last two chapters.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE

Acknowledgements

The Scaling Community of Practice and the authors are indebted to the many colleagues from the funder partner organizations that participated in this Initiative with case studies and in commenting on the findings. They also wish to express their special thanks to the Agence Française de Développement and to Eric Beugnot for the financial support extended to make this Initiative possible. They also thank Charlotte Lane for her editorial support in finalizing this paper. The authors bear sole responsibility for the contents of the paper.

I. Introduction: Background, Motivation and Scope of This Report

A. The Background of This Report

The pursuit of sustainable development and climate impact at scale – or scaling, for short – has been receiving growing attention in the international development community over the last few years. The exponential growth of the Scaling Community of Practice (SCoP) membership from some 40 participants at its founding in 2015 to about 4,000 in 2024 is one indicator of this interest. There are many others, including statements by leaders of major development finance institutions, such as the World Bank’s President in his speech at the International Monetary Fund (IMF)/World Bank Annual Meeting in October 2023, and the inclusion of achieving impact at scale now found in many mission statements of international and national development agencies.

This is largely due to recognition that approaches to development and development finance are not having the needed impact relative to the size of the problems, as evidenced by the fact that the world is off track to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. In addition, there is general acknowledgement that despite their tremendous promise, investments in innovation have not realized their potential. While donors, national governments and the private sector could and should allocate more financial resources to meet the development challenge, that is an unrealistic solution given the size of the financing gap and the fact that the history of development finance tells us that money alone will not do the trick. Therefore, scaling development impact for given resources – improving long-term impact-cost ratios – is increasingly being turned to as the solution. In this understanding, scaling is not simply doing more, though it is often used that way. It involves achieving economies of scale, scope, continuity and cooperation so that greater impact can be achieved with whatever financing can be mobilized. For funders it means, ideally, that scaling by domestic actors continues after funder efforts end and reaches more people and places as needed to address development challenges.

Despite the growing buzz around scaling, and while there are of course examples of successful scaling, most development observers would agree that not enough is being done by the principal development actors – governments, private investors, civil society, and development funders – to pursue scaling systematically. To the extent that scaling does occur, it is mostly ad hoc and opportunistic, and not the result of a deliberate organization-wide strategy. What is needed for scaling to really have an impact is for development actors to mainstream scaling, i.e., to systematically integrate scaling into their strategies, business models, operations, and managerial and staff mindsets and incentives. While funders are not the only relevant actors, many implementing organizations and local actors report feeling constrained from systematically pursuing scaling approaches because of the way funders operate.

In this context in early 2023, the SCoP launched the “Mainstreaming Initiative.” The Mainstreaming Initiative is a two-year “action-research” effort to study mainstreaming scaling in international development funder organizations. It followed a year-long preparation process, which included the preparation of a background paper and intensive discussion among the SCoP’s members. The purpose of this initiative is to (i) assess progress to date, (ii) develop lessons learned, and (iii) disseminate those lessons to encourage and inform further mainstreaming by interested organizations. To facilitate learning, the initiative focuses on funders that are interested in partnering with the SCoP and known to have made some progress in mainstreaming scaling. This interim synthesis paper reports on the results of the first year of the Mainstreaming Initiative.

B. Focus on Funders and Their Challenges in Scaling

Why the focus on funders? Funders generally do not directly implement development programs, projects or policy changes. However, they have an outsized influence on program goals, strategies, results and deliverables; approve the designs and workplans of the organizations and projects that they fund; and often require specific implementation, procurement and monitoring and evaluation practices. Many funders also provide training, technical assistance and capacity building for program delivery as well as support for policy and institutional reform. Indeed, funder money, while a small share of national and sectoral budgets in most countries, often represents the lion’s share of discretionary financial resources, i.e., those available to initiate and support change. Therefore, funders carry a special responsibility to ensure that their funding practices and technical support facilitate, rather than impede, scaling by the recipients of their funds.

Aside from providing finance, funders could and should serve as important champions, facilitators, intermediaries and providers of incentives for the scaling process. Unfortunately, most funders do not explicitly focus on funding scaling let alone target sustainable impact at scale. In fact, many traditional funder practices inadvertently undermined scaling efforts:

- Funders typically support time-bound (2-4 year), one-off projects. They focus on delivering impacts for project beneficiaries during the project’s duration, but not beyond project closeout.

- Funder staff are rewarded for presenting ambitious, innovative and complex projects to their management and boards. Staff receive less recognition, if any, for supporting the design and implementation of projects that ensure sustainability and scalability by others beyond project end. Similarly, scaling follow-up to previous projects is often less valued by management than starting new ones.

- Funders have not done enough to align with national priorities and ownership. Often, they do not align with and address country-specific public or private sector constraints on financial resources and institutional capacity that stand in the way of long-term, sustainable scaling.

- The “aid architecture” is heavily fragmented. Funders operating in the same development space (geography, sector, thematic area, etc.) often have poor coordination, siloed reporting systems, duplicative efforts, etc. While partnerships are almost always necessary for successful scaling, international development funders have not overcome systemic obstacles to successful collaboration despite decades of efforts.

- Supporting “innovation” has become popular in the past fifteen years, as demonstrated by the proliferation of innovation labs, challenge funds, incubators, accelerators and hackathons. In too many cases, such approaches have not been accompanied by efforts of systems change, i.e., to address the shortcomings of local systems and enabling environments that perpetuate development problems. Innovation funding generally has neither created institutions that can take innovations to scale (“intermediaries”) nor allocated the necessary funding to scale promising innovations. Instead, innovation funders presume that scaling will either happen spontaneously or is the responsibility of unspecified “other” institutions. As a result of this “magical thinking,” scaling often does not happen and the enormous potential of innovations goes unrealized.

- Project monitoring and evaluations focus on delivery against project plans, timely disbursement of funds, narrow results targets and impact. Monitoring and evaluation processes usually fail to collect data to support future scaling efforts. They typically do not focus on selecting among competing approaches; minimizing complexity and unit cost; identifying the role of context, social issues and the political economy across relevant stakeholders; or assessing the enabling environment. In addition, monitoring and evaluation processes rarely examine whether projects put in place conditions for sustainability and scaling impact beyond project end.

Of course, it is not enough for funders to focus on scale and scaling – they also need to do so in ways that scale for transformative and sustainable impact, or what might be called “good scaling.” Therefore, we believe that it is particularly important for funder agencies to support scaling in a more systematic and more effective manner than they have done hitherto. Many funder agencies now demonstrate a commitment to impact at scale in their strategies and communications. Given this stated priority, we believe it is particularly important for funder agencies to make intentional changes to the way they operate that enable them to support scaling effectively and systematically and achieve the sustainable impact at scale they aspire to.

C. The Case Studies of Funder Mainstreaming Experience

The Mainstreaming Initiative organized case studies of international development funder organizations that explored five main questions: (i) why certain organizations have pursued mainstreaming; (ii) what specific forms mainstreaming is taking internally and in what areas progress has been made (or not); (iii) what challenges commonly arise and how they are addressed; (iv) whether funders have mainstreamed good scaling practices; and (v) what lessons can be derived for organizations either contemplating mainstreaming and looking for direction and support, or wishing to progress beyond their existing efforts. What the case studies generally did not look at was whether progress on mainstreaming led to increased scaling, greater impact at scale, or both, as this would have required detailed evaluations of the scaling performance of organizations for which the initiative did not have sufficient resources. Moreover, since many funder organizations have either not progressed very far with the mainstreaming agenda, or mainstreaming is relatively recent, an evaluation of its impact would have been, at best, of limited value. However, where information was available on the impact of mainstreaming scaling, the case studies incorporate this information.

Underpinning the case studies are the definitions, principles and lessons that have emerged from research on good practice in scaling, as found in the Principles and Lessons of Scaling compiled by the Scaling Community of Practice. Box 1 (next page) briefly summarizes the most relevant of them.

In the spirit of a highly collaborative “action research” undertaking, the case studies were either prepared by experts from within the funder organizations with support from the Scaling Community of Practice or written by Community of Practice members with cooperation from the organizations. The case studies were guided by a broad set of questions identified in the Concept Note for the Mainstreaming Initiative (see Annex) and adapted in each case to the specific conditions of the funder organization under review. Funding for the case studies was provided by the Scaling Community of Practice (including an earmarked grant by Agence Française de Développement), by financing and in-kind contributions from the organizations, and by pro bono contributions of the authors.

In 2023, we were able to conduct twelve case studies of mainstreaming for a broad variety of actors in international development. The mix of organizations covered is diverse (see Table 1 on page 7). It includes: (i) large bilateral and multilateral funders that mostly finance (and sometimes implement) development projects across a broad range of sectoral and thematic areas; (ii) vertical funds that focus more narrowly on specific sectors or subsectors; (iii) research and innovation funders and research organizations; (iv) large international NGOs that mostly implement donor projects; and (v) small foundations either that provide grants for innovations or that fund both innovation and scaling. For more information about each funder organization, see the case studies posted on the SCoP website.

A second phase started at the beginning of 2024 with an additional 10 or more case studies to be prepared by mid-2025. The second phase of the Mainstreaming Initiative is expected to have a special focus on the role and practices of foundations and vertical funds (i.e., single purpose/sector funds) and on the health sector. It will draw more extensively on the experience of recipients in developing countries, develop an analytical tool to track and support mainstreaming in funder organizations, and complete a parallel effort to assess whether and how scaling has been incorporated into the evaluation practices of the independent evaluation offices of official development funders. The continued research on funder practices will be complemented by active outreach efforts in the form of webinars under the auspices of the Mainstreaming Working Group of the Scaling Community of Practice and by outreach to individual funder organizations or groups of funders to disseminate and discuss the findings to date of the Mainstreaming Initiative. Ultimately, our goal is to inform and influence the operational approaches and practices of funder organizations so that sustainable scaling becomes their default approach and is an integral part of their missions, policies, implementation support, management and staff incentives and monitoring and evaluation practices.

Table 1: Case studies completed and ongoing under the Mainstreaming Initiative(All case studies are posted here: https://scalingcommunityofpractice.com/resources/case-studies/) |

||

| Organization | Type of the funder organization | Case Study Status |

| Phase 1, 2023 | ||

|

Large bilateral official funder of institutional and systems strengthening; broad sectoral/thematic coverage | Posted |

|

Large international NGO; broad sectoral/thematic coverage | Posted |

|

Large multilateral development bank for Latin America; broad sectoral/thematic coverage | Posted |

|

Vertically integrated research/implementation of fortified food | Posted |

|

Small multilateral official funder; focused on vertically integrated research/implementation of fortified food | Posted |

|

Medium-sized multilateral official funder; focused on agricultural development, especially for small family farmers | Posted |

|

Small foundation focused on innovation and scaling of agricultural and rural development innovations | Posted |

|

Department of a large bilateral official funder; focused on innovation and scaling in agriculture and food systems | Posted |

|

Small bilateral official funder of innovation and scaling of health sector solutions | Posted |

|

Small multilateral official funder of innovation and scaling private for private enterprises; affiliated with IDB | Posted |

|

A multilateral international agricultural research organization | Posted |

|

Large international NGO; broad sectoral/thematic coverage | Posted |

|

Review of funder practices in the education sector | Posted |

| Phase 2, ongoing | ||

|

Large multilateral development bank for Africa; broad sectoral/thematic coverage | June

2024 |

|

Small multilateral funder of maternal and child health and nutrition interventions and system strengthening; affiliated with the World Bank | June

2024 |

|

Small Foundation; focused on funding nutrition research and advocacy | June

2024 |

It is important to note a few caveats. First, the case studies are neither a random nor a representative sample. Rather, in most cases they were drawn from organizations that we know and that made some efforts at mainstreaming. Second, selection generally required cooperation from the organization, again affecting the sample composition. Third, the case studies do not represent formal, in-depth, independent evaluations, but learning efforts jointly by the funder organizations and the team of experts from SCoP with limited resources and time frame. Fourth, given the diversity and small sample size that limits the degrees of freedom for any particular type of organization, the analysis is of necessity qualitative; and the patterns identified, and conclusions and recommendations drawn need to be taken in that context. However, in the interest of bringing to bear as much evidence as possible for our conclusions, we selectively draw on experience with funder practice beyond the case studies, especially the above mentioned background paper and consultations leading up to the Mainstreaming Initiative.

The structure of this interim synthesis report is as follows: Section II explores what roles funders play in supporting scaling and the overall state of mainstreaming scaling. Section III explores how funders identify and describe the main enabling factors of mainstreaming that emerged from the case studies, from integrating scaling into mission and vision, operations and MEAL to the importance of leadership and changes in organizational culture and incentives. Section IV analyses the extent to which funders have integrated good scaling practices into their mainstreaming efforts. Section V and VI conclude with summaries of preliminary lessons respectively for individual funders organizations and for the funder community at large. Annex 1 presents the high-level questions addressed by the funder case studies. Annex 2 provides an overview of tradeoffs and tensions that funders face and need to manage as they mainstream scaling into their operational practices.

II. Funder Roles and the Progress on Mainstreaming

A. Funder Roles

As noted in Section I, there is a great diversity of funders in our sample. For the analysis of our findings, it helps to categorize them broadly by purpose and type (Table 2, next page). As regards purpose, we divide them into funders of research, funders of innovation with scaling, and funders of projects with scaling. For each type, we distinguish between small and large funders, and among large funders between bilateral and multilateral official agencies, implementing or intermediary partners, and vertical (i.e., single purpose) funds. Several funders fall into more than one category, both in terms of the purpose and their type. For example, USAID Feed the Future (FTF) supports both research and innovation with scaling. The Systematic Observations Financing Facility (SOFF) is both a small official funder and a vertical fund. Five of the funder agencies are principally engaged in supporting agriculture, rural development and food systems making possible a deeper dive into the specifics of scaling in that sector. Building on the experience of our Mainstreaming Initiative, much could be gained from future research comparing funders with similar roles and sectoral or thematic emphases.

Table 2: Funders by purpose and type |

||||

| Small | Large or within Large Organizations | |||

| Type

Purpose |

Foundations or Official Agencies |

Bilateral and Multilateral Agencies |

Implementing or Intermediary Partners | Vertical Funds1 |

| Research | ECF | CGIAR, USAID FTF | ||

| Innovation with scaling | GCC, Syngenta Foundation, HarvestPlus | IDB-Lab, USAID FTF | ||

| Projects with scaling | Syngenta Foundation,

SOFF |

GIZ, IDB, AfDB | CARE, CRS | IFAD, SOFF, GFF |

- Vertical funds are focused on a specific issue, purpose, or sectoral area.

Acronyms: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Catholic Relief Services (CRS), Systemic Observations Financing Facility (SOFF), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United States Agency for International Development’s Feed the Future (USAID FTF), Inter-American Development Bank – Lab (IDB-Lab), Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR)

Smaller funders and those with narrower mandates (especially vertical funds) appear to find it easier to mainstream scaling than larger funders or those with a broad mandate. The latter types of funders face greater internal bureaucratic obstacles, disincentives and inertia, and find it difficult to adjust their traditional one-off project funding approach that is problematic for reasons outlined above. Differences are not attributable entirely to the project model but at least equally to how they and their governing bodies define and measure success. Many smaller funders, foundations and vertical funds work through projects that incorporate longer time horizons (e.g., tacit commitments to multiple rounds of funding) and allow for learning and strategic pivots.

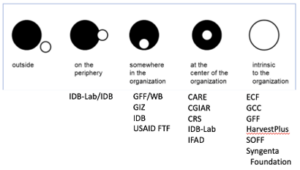

Using the six International Development Innovation Alliance (IDIA) innovation and scaling stages, we characterize funder roles according to where they operate along the innovation-scaling spectrum. As demonstrated in Figure 1, there are overlaps across the types of funders across the six IDIA stages along the innovation-scaling spectrum. So, in principle, the entire scaling pathway is covered with appropriate financing and effective hand-off from one funder to the next is possible – in principle. However, the case studies and other evidence demonstrate that, in practice, there are significant gaps in funding support along the scaling pathway since funders continue to focus on innovation or address issues through one-off projects at a limited scale. As they do not integrate scaling systematically, this limits their ability to scale their own projects, innovations that they may have developed elsewhere, or the innovations originating with other organizations. In particular, research and innovation funders (operating at stages 1-3) should be able to hand-off successful initiatives to project funders (stages 4-6) but generally have problems in finding suitable partners.

Figure 1: Stages at which funders could support scaling, within their mandates and resources

Note: This figure is only a linear approximation of the process of scaling, especially in stages 1-3. Scaling is often non-linear, iterative and simultaneous. For example, systems strengthening and capacity building can often occur concurrently with innovation, piloting or initial projects, precede them, or be characterized by alternating systems changes and design-test-learn-revise cycles. HarvestPlus operates across the entire pathway and is, therefore, not included. Acronyms: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Catholic Relief Services (CRS), Systemic Observations Financing Facility (SOFF), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United States Agency for International Development’s Feed the Future (USAID FTF), Inter-American Development Bank – Lab (IDB-Lab), Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), international non-governmental organization (INGO). |

Unfortunately, the links between research and innovation funders and project funders tend to be weak. For example, there is no systematic process of integrating agri-food innovations developed by the CGIAR with large donor agri-food projects, such as those of IFAD. The integration of innovations developed by USAID’s own Agricultural Innovation Laboratories and its Feed the Future projects does happen, but not systematically. Similarly, there are few links between GCC supported innovations and health projects funded by Global Affairs Canada. The same holds true for IDB-Lab and IDB. This limited coordination between research and innovation funders and project funders contributes to the well-known “valley-of-death” between innovation and scaling. It is encouraging that some research and innovation funders have pushed downstream along the scaling pathway by funding stage 4 (‘Transition to Scale’), helping ensure that innovations are scale-ready and supporting partnerships.

Similarly, funders generally do not focus on hand-off at project end to government, private business and/or other funders for sustainable operation at scale, i.e., stage 6. For this reason, innovations or project interventions are often not aligned with prevailing implementation modalities and capacity, budgetary resources or viable private business models. Bridging these gaps is an important challenge that funders must address if they wish to systematically support scaling.

An important consideration regarding funder roles is the extent to which funders serve as facilitators or intermediary institutions in support of systems change with policy advice, capacity building, coordination and investment mobilization. Systems change is generally a necessary complement to scaling, and support for system change can help achieve sustainable impact at large scale. The case studies contain many noteworthy examples of funder organizations that extend their roles beyond funding to support systems change. Larger (project) funders are generally better equipped to do so than smaller funders, particularly official funders like the GIZ, IFAD and GFF. These funders work directly with governments and can support investments in infrastructure, changes to the policy enabling environment and strengthening public sector capacity. Conversely, innovators and innovation funders are often restricted by their mandates and resources from supporting systems strengthening. As a result, scaling by smaller funder initiatives is rarely accompanied by systems change, creating significant constraints. In principle, hand-off to larger project funders offers important opportunities for the latter to support scaling with systems change. But, in practice, support for systemic reforms by large funders is rarely coordinated with or explicitly linked to innovations supported by smaller funders or even to projects financed by the same large funder.

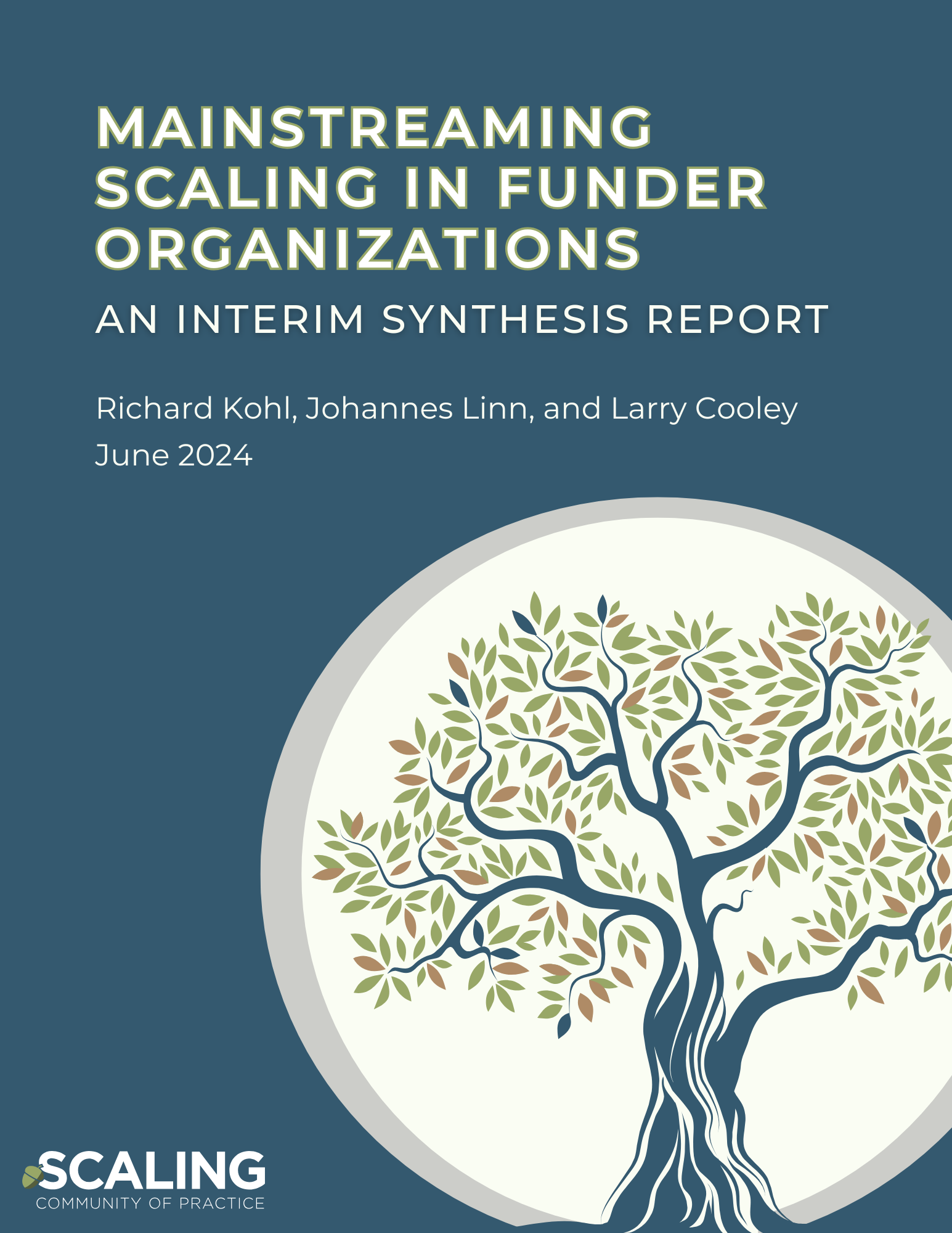

B. The State of Mainstreaming Scaling

The case studies allow insight into the current state of mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations. We use a simple framework for describing the state of mainstreaming within funder organizations as shown in Table 3 and Figure 2 (next page). The framework employs five categories of progress in mainstreaming: (i) scaling is outside the organization; (ii) scaling is on the periphery of the organization; (iii) scaling is prominent somewhere in the organization; (iv) scaling is located at the center of the organization as a key corporate goal, but not implemented throughout; and (v) scaling is intrinsic to the organization. However, we need to stress that the placement of funders in Figure 2 is only indicative and a snapshot at a particular time. For example, according to our case study, IDB falls into category (iii) (somewhere in the organization), but since IDB has recently approved a new corporate strategy which places scale at the center of IDB’s corporate mission, it could well move into category (iv). Furthermore, while in general it would be desirable for funders to move from top to bottom in Table 3 (next page), or from left to right in Figure 2 (next page), not all funder organizations should necessarily aim for the “intrinsic” outcome in their mainstreaming efforts. For example, for organizations that fund emergency humanitarian assistance, it may be appropriate for mainstreaming to fall “somewhere” or “at the center.”

Overall, the case studies are consistent with the hypothesis that funders are paying more attention to scaling. All the funders in the case studies have at least some scaling within their organization (Figure 2). Moreover, the case studies confirm that many funders are making efforts to move from left to right across the mainstreaming spectrum. Let us take a brief look at individual funder cases from right to left in Figure 2:

- Six funders (ECF, GCC, GFF, HarvestPlus, SOFF and Syngenta Foundation) stand out as having decided that intrinsic scaling is appropriate to their organization. These funders made significant efforts and progress over the last 5-10 years in mainstreaming scaling throughout their organizations with strong leadership from the top. They have systematically oriented their funding (and delivery) practices to support that decision.

- Five funders (IFAD, CARE, CRS, CGIAR and IDB-Lab) have placed scaling centrally in their organizational vision, mission and goals with strong leadership from the top. It is not clear in some of these cases if there is an organizational consensus to move further on mainstreaming (making it “intrinsic”) or whether they have decided that “centrally” is what is appropriate for their organization. However, all these organizations are still in the process of rolling out scaling throughout their organizations and with continued efforts some of them at least can be expected to move into the last column eventually.

- Three funders (GIZ, IDB and USAID FTF) are shown in the middle column, indicating that scaling is pursued somewhere (and possibly in multiple locations) in the organization, but is neither at the core of the funder’s mission and vision nor systematically mainstreamed into the overall funding practices of the organizations. As noted earlier, IDB may move to the right as its new corporate strategy focuses on impact at scale.

- Figure 2 also identifies two funder pairs. The GFF/World Bank (WB) pair is placed in the middle column, since the GFF is a trust fund housed at the World Bank, and GFF and the World Bank collaborate and cofinance in support of impact at scale. The IDB-Lab/IDB pair is in the second column from the left, since the IDB-Lab case study notes that there are few effective links with IDB programs. Therefore, the pair is considered to have mainstreaming “on the periphery” while IDB-Lab itself has mainstreaming “at the center of the organization.”

| Table 3: Criteria for categorizing funders by state of mainstreaming | ||||

| Incorporated into corporate-level vision, goals | Toolkits and Frameworks developed | Integrated into Strategy, Operations and Procedures | Adoption or Utilization Level | |

|

Not | Not | Not | Not |

|

May be mentioned | Not for the organization | Not | Ad hoc |

|

May be mentioned | Developed or relatively advanced for parts of the organizations | Not systematically yet, or still being operationalized | Ad hoc, low levels, not required |

|

Central to the organizations’ core goals | Developed or well advanced | Relatively advanced | Started, still a small percentage |

|

Central | Developed | Largely integrated | Throughout most of the organization |

Figure 2: Funders placement on the mainstreaming spectrum

Notes: Figure 2 adapts a graphical device developed by Sabine Junginger (Sabine Junginger, 2009 Https://Www.Researchgate.Net/Publication/266281802_PARTS_AND_WHOLES_PLACES_OF_DESIGN_THINKING_IN_ORGANIZATIONAL_LIFE) The figure includes ECF and GFF based on preliminary work with these two funder organizations. We include two funder pairs. The GFF/World Bank (WB) pair, since the GFF is a trust fund housed at the World Bank. The IDB-Lab/IDB, since the IDB-Lab is housed within the larger IDB. Global Affairs Canada, the main Canadian foreign assistance organization, was not included among our case studies. We therefore cannot assess where, on its own, it would be placed in the figure. Acronyms: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Catholic Relief Services (CRS), Systemic Observations Financing Facility (SOFF), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United States Agency for International Development’s Feed the Future (USAID FTF), Inter-American Development Bank – Lab (IDB-Lab), Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). |

Four additional findings emerge from the overall mainstreaming experience of our case studies:

- It appears that smaller funders and those with narrower mandates (especially vertical funds) find it easier to mainstream scaling than larger funders or those with a broad mandate. The latter seem to face greater internal bureaucratic obstacles, disincentives and inertia, and to find it difficult to adjust their traditional one-off project funding approach that is problematic for reasons outlined above.

- Differences between small and large funders are not attributable entirely to the project model. Many smaller funders, foundations and vertical funds work through projects that incorporate longer time horizons (e.g., tacit commitments to multiple rounds of funding) and allow for learning and strategic pivots. SFSA is a good example of this type of small foundation.

- Some research and innovation funders have pushed downstream along the scaling pathway into funding stage 4 (‘Transition to Scale’), helping ensure that innovations are scale-ready, and supporting partnerships. Nonetheless, as noted in Section II A., they have so far had limited success in linking up their innovations with the resources and capacities of larger project funders, governments and the private sector to help recipients overcome the “valley of death.” Nonetheless, some innovations supported by those funders (like GCC) that have been developed by social enterprises do go to scale; those that require uptake by the private or public sector have had less success.

- Mainstreaming scaling takes time. IFAD has been working on this agenda for twenty years and it remains a work in progress. For other funders (GIZ, CRS, CARE, Harvest-Plus, etc.), it has been 10 or more years of progressive efforts to mainstream scaling. The CGIAR began serious mainstreaming efforts around 2020 and expects this to continue until the end of the decade.

In the next section of this report, we unpack how funders have pursued the mainstreaming goal, followed in Section IV by an assessment of how and how far good scaling practices were incorporated into the mainstreaming process by the funders included among our case studies.

III. Enabling Factors of Mainstreaming Scaling

We know from prior experience that a number of enabling factors can support the mainstreaming of scaling in funder organizations. These include leadership; integrating scale into organizational mission and vision; operational instruments, policies and practices; organizational, technical and budget resources; analytical tools, learning and knowledge; evaluations; and planning and sequencing the interlocking incentives in support of a scaling mindset and practice. In this section we examine for each of these factors how our prior assumptions are borne out by the experience of the case studies in terms of whether and how the case studies confirm the priors for each type of enabling factor.

A. Leadership to Drive Scaling

Across the case studies, the most important enabling factor for mainstreaming is leadership from top management. This is consistent with the prior understanding that leadership needs to be relentless champions for scaling. The SCoP Scaling Principles emphasized the centrality of leadership for scaling itself. The case studies confirm that leadership is as important for mainstreaming scaling. Organizational leaders must create a clear vision, understanding and expectation of role of scale and scaling for the funder organization, including how they are defined and measured. Leaders need to drive integration into operational policies and procedures, and realign organizational structures, resources, culture and incentives around their vision. Creating common definitions and language is a critical, but insufficiently acknowledged, role for leadership. This common lexicon is especially important if mainstreaming includes a transition from a transactional to transformational approach to scaling.

Leadership was a factor for the relatively successful mainstreaming record of ECF, Syngenta Foundation, HarvestPlus, and others. Recently, the promotion of an explicit scaling agenda by the presidents of the IDB and the World Bank started a process under which impact at scale is getting more systematic attention. One of GCC’s co-Executive Directors is an active proponent of scaling both internally and in the innovation community. As a result of the new Executive Director who took over in 2017, the Syngenta Foundation successfully put scaling at the center of its corporate ambition. For CARE, the initiative came from senior management and included creating a Vice President for Impact and Innovation generally and a Director of an Impact at Scale. In the cases of IFAD and GIZ, changing priorities of and attention from top leadership largely explains the ups and downs in attention to mainstreaming. IFAD is an example of the potential for discontinuity in the focus on mainstreaming scaling when leaders change.

Leadership needs to ensure that middle management and staff have incentives to implement mainstreaming objectives, as demonstrated by the experience of IFAD and other funders. This requires a clear articulation of operational goals, accountability and rewards for achieving targets as well as resources that enable managers and frontline teams to deliver (see Section III D: Organizational, Technical, and Budget Resources).

Support and, in some cases, pressure from the governing bodies of the funder organizations (boards, ministries, etc.) can also drive mainstreaming (e.g., for Syngenta Foundation, CARE, CRS and GFF). The push to mainstream scaling in the CGIAR system was largely a response to donor pressure for greater impact at scale and accountability for that impact. In the case of IFAD, the fact that management had committed to a mainstreaming agenda and specific operational performance metrics under various resource replenishment negotiations facilitated some degree of continuity in the institutional focus on scaling achieved across leadership cycles.

Bottom-up stakeholder or partner pressure in recipient countries is not generally cited in the case studies as a driver for mainstreaming. GFF is to some extent an exception. Senior government representatives from recipient countries play an active role in the GFF governance structure and have pushed for alignment of funder support with national priorities for long-term universal health objectives. More generally, though, not many recipient country governments have had leadership roles in developing systematic approaches to defining and pursuing longer-term scaling pathways as part of their development strategy implementation. The development paradigm of the People’s Republic of China is an exception, as are selected development programs of Ethiopia (agriculture), India (health in particular), Indonesia, Vietnam and Mexico. In these cases, governments did push their external funder partners to support scaling programs, but did not aim to change funders’ operational practice more generally in the direction of mainstreaming scaling.

Bottom-up pressure or demonstration of success from within the funder organization can help. But it rarely provides the leadership needed for corporate-wide mainstreaming. In the CGIAR case, the creation by staff and middle management of a scaling framework and tools helped advance scaling mainstreaming rapidly once senior management prioritized scaling in response to pressure from funders.

B. Integrating Scale into Corporate Mission, Vision and Goals

An obvious first step in mainstreaming scaling is to incorporate scaling and explicit scale goals into funders’ corporate vision and mission statements. An increasing number of funder organizations have done so (Box 4, on next page). This is a relatively simple, but crucial, step to take as it provides the foundation for other essential steps.

Beyond announcing their intention to pursue impact at scale as part of their vision and mission statements (often linked to support of the SDGs), a few funders also announced concrete and measurable medium or long-term goals for impact at scale. HarvestPlus, for example, has the goal of reaching one billion consumers with nutrient-enriched food by 2030. IFAD, in 2012, announced its goal to reach 90 million farmers and take 80 million people out of poverty. SOFF set an explicit, quantitative target to close the weather and climate observations gap in Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries over a ten-year period. In addition to its poverty goals, the CGIAR has concrete goals for improvements in food security (e.g., yields) and nutrition (e.g., micronutrient consumption) and natural resources (e.g., deforestation and agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. CRS has six strategic platforms as part of its 2030 Strategic Vision, and each has quantitative targets.

However, many funders do not set quantitative long-term impact goals. Instead, they pursue specific short- to medium-term goals as part of their results management frameworks, often stated in terms of absolute numbers or changes relative to a baseline. From a scaling perspective, it is more appropriate to express goals relative to a long-term target or in terms of the fraction of a needs gap to be filled.

Closely related to setting scale targets and announcing scaling as a corporate goal is the need to define what is meant by scaling for the funder organization. In developing the concepts and definitions of scale and scaling, funders should focus on transformational scaling and

Box 4: Examples of scaling mission statements

- CRS: “Catalyze Humanitarian and Development Outcomes at Scale” and “The synergy and opportunity that is created from direct services, to systems change, to catalyzing outcomes at scale.”

- CARE Vision 2030: “CARE contributes to lasting impact at scale in poverty eradication and social justice, in support of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).”

- CGIAR Strategy and Results Framework 2016-2030: “350 million more farm households [in addition to 100 million reached by 2022] have adopted improved varieties, breeds or trees, and/or improved management practice; 100 million people, of which 50% are women, assisted to exit poverty.”

- GCC: “Grand Challenges Canada is dedicated to supporting Bold Ideas with Big Impact®.”

- HarvestPlus: “By 2030, our strategic objective is to help partners worldwide sustainably reach 1 billion people by embedding biofortified crops and foods in food systems.”

- Syngenta Foundation: “To strengthen smallholder farming and food systems, we catalyze market development and delivery of innovations, while building capacity across the public and private sectors.”

- IFAD: “Scaling is mission critical.”

- SOFF: “SOFF will ensure that SIDS and LDCs have the capacity and financing to deliver on their GBON commitments.”

not just on transactional scaling. Transformational scaling is about achieving long-term goals whereas transactional scaling focuses on more money, on larger projects and on growing an organization financially (Box 5 next page). Transformational scaling prioritizes continued scaling and impact by domestic actors and resources after project end to achieve a well-defined long-term goal. So far, only a few funders – CRS, HarvestPlus, IFAD, Syngenta Foundation, and arguably GCC and GFF – have focused explicitly on transformational scaling. IFAD, for example, carefully considered and announced its definition of scaling:

“Scaling up takes place when: (i) bi- and multilateral partners, the private sector and communities adopt and disseminate the solution tested by IFAD; (ii) other stakeholders invest resources to bring the solution at scale; and (iii) the government applies a policy framework to generalize the solution tested by IFAD (from practice to policy).”

The corporate definition of scale and scaling must be widely disseminated and understood among staff, recipients and partners for it to be impactful. IFAD incorporated its approved definition of scaling into operational and evaluation policy to avoid conflicting interpretations of mainstreaming scaling in different units of the organization.

Finally, the design of the mainstreaming effort needs to have a clear vision, definition and implementation pathway for the mainstreaming efforts themselves. This extends beyond how organizations wish to achieve ultimate impact, to include intermediate concrete markers for progress with the mainstreaming effort and the pathway of introducing organizational change. These markers can then serve as benchmarks for assessing progress in monitoring and evaluating the mainstreaming process during implementation (see Section 5 G: Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning.).

C. Funders’ Operational Instruments, Policies and Practices for Scaling

Funders’ financial instruments as well as their funding policies and processes need to be tailored to support their recipients in advancing along the scaling pathway. Foundations and innovation funders, such as GCC and Syngenta Foundation, have flexibility in deploying grants in the early stages of the scaling pathway, and then pivoting to loans, guarantees and equity investments in the later stages. GCC, for example, supports a series of Transition to Scale grants, social enterprise coaching, communities of practice and intermediary organizations that foster linkages to public sector actors. The larger multilateral and bilateral development agencies tend to be more constrained in their use of financing instruments, relying mostly on either standard loans or grants. Results-based funding instruments can also support scaling effectively since they allow greater flexibility for implementing entities to apply the tools of adaptive management in the scaling process. GFF and SOFF employ results-based funding; however results-based funding, programmatic or performance-based approaches only really support sustainable impact at scale if they are used to achieve transformational scaling.

Funders’ operational policies and procedures include criteria for the preparation, design, selection and approval of projects; supervision of implementation, procurement and contracting; quality assurance, adaptive management and risk management (see Section III F: Results Metrics, Monitoring, and Evaluation). Operational policies and procedures should include explicit reference to the conditions necessary for scaling, as demonstrated by some of the case studies (e.g., IFAD, GCC, and the Syngenta Foundation). Small organizations, like GCC, Syngenta Foundation, and HarvestPlus, made considerable progress in mainstreaming through persistent, ongoing leadership with varying degrees of integration into formal processes and procedures. The CGIAR is embarking on what will hopefully be widespread internal adoption of its Innovation Package and Scaling Readiness framework and tools. However, without strong leadership and adequate organizational, technical and budget support for frontline teams in the funder organizations, changes in policies and processes will likely have limited impact in driving changes in frontline operational practice towards scaling, risk taking and adaptive management.

Logic and experience suggest the importance of job descriptions, performance evaluations, professional development, training requirements, salaries and promotions (i.e., Human Resource policies and practice) in the successful execution of any corporate policy. To support scaling, these need to include criteria reflecting a funder organization’s determination to support scaling. We have found little evidence in the case studies that funders intent on scaling reflect this in their corporate Human Resources policies.

D. Organizational, Technical and Budget Resources for Scaling

Dedicated organizational, technical and budget resources are required to ensure effective and sustained mainstreaming. Some of the case study funder organizations (e.g., CARE, CGIAR, CRS, GIZ and USAID FTF) have dedicated technical, organizational and budgetary resources to support and sustain the mainstreaming process. However, where they exist, scaling support units are quite small: USAID’s FTF and CARE’s scaling support units are composed of a few people and GIZ has one person playing that role. In contrast, the CGIAR has a central support unit, trained several hundred staff to act as local resource people and introduced a small scaling fund to support innovation teams working to achieve Scaling Readiness. IFAD had a scaling capacity in its Central Technical Support unit for a few years, but later disbanded it.

A central unit can facilitate mainstreaming and support operational units to integrate scaling, but it is not sufficient. In all cases where scaling has become intrinsic to the organization (including ECF, GCC, GFF, HarvestPlus, SOFF and the Syngenta Foundation), it is an “all-of organization” effort and sufficient resources are allocated to front line staff to pursue a scaling approach. However, in practice this does not happen. Therefore, while front-line staff and project teams generally recognize the benefits of a systematic scaling approach when it is presented to them as a way to improve the effectiveness of their projects, they resist when confronted with a scaling mandate that is not adequately funded. In practice, many staff, especially in the larger official funder organizations (e.g., GIZ, IFAD and CGIAR), see themselves as already bearing a heavy burden in meeting cumulative “unfunded mandates” in the design, implementation and evaluation of projects. These mandates include a multitude of policy and fiduciary requirements (gender and social inclusion, environment and climate change, community outreach, private sector engagement, anti-corruption, etc.) that have been added to staff workloads, often without additional administrative or budget resources. As a result, middle managers and frontline staff often resist, when confronted with an unfunded mandate to incorporate a scaling perspective in their work, tend to ignore or honor it only in a pro forma manner.

Generally, smaller funders (e.g., Syngenta Foundation, HarvestPlus, ECF and GFF) find it easier to incorporate scaling into staff’s operational practices and incentives and the overall organizational culture than larger ones. With a short chain of command, leadership may more directly influence staff behavior and better understand staff’s constraints. Rather than mainstreaming scaling throughout the institution, large funders find it easier to focus on scaling in selected programs, as seen through the World Bank’s GFF and its new Global Challenge Program. The GFF provides targeted resources to complement the financing of World Bank loans for maternal and child health. The GFF’s resources allow scaling to be systematically supported in these loans through technical assistance for country-driven strategy formulation, institution building, policy reform and resource mobilization in support of a longer-term scaling pathway. Given the challenges that larger funders face in mainstreaming, a strategy that uses a phased approach, starting with narrow objectives (“scaling somewhere in the organization”, Figure 2) may be the most effective approach, as long as the objective is transformational scaling. Over the long haul, efforts can spread the mainstreaming agenda throughout the organization. The CGIAR is a good example of this; mainstreaming is being rolled out starting with early adopters who are self-motivated to adopt it. Combined with coaching, financial support and incentives, the CGIAR strategy is to create a critical mass of adopters that will then spread via example throughout the system.

E. Decentralization

Funder organizations in our case studies recognize that local context and ownership are critical for effective scaling (see also Section IV D: Country Ownership and Localization). This, in turn, requires that funder staff understand local context, needs and preference of local stakeholders. While usually not driven by scaling considerations, some organizations have set up local offices in recipient countries and relocated staff to recipient countries (“decentralized”) or recruited locally for these offices. Decentralization has both positive and negative effects for mainstreaming scaling. It facilitates mainstreaming through a better understanding of local context, political economy and priorities, enabling funder organizations to establish long-term relations with key local stakeholders. It also allows staff to identify and take advantage of often transient windows of opportunities. On the other hand, greater independence of country offices can make organization-wide adoption and implementation of a scaling approach more challenging. Country staff can feel threatened by efforts to apply and refine ”their” flagship programs through a scalability lens.

Organizations without local offices have found other solutions. One innovation funder, GCC, shifted the emphasis away from universities and research centers located in the Global North to those in the Global South, and from researchers to social entrepreneurs who have a better understanding of local markets and public systems. In general, though, our research to date suggests that smaller funders find it more difficult to decentralize their operations.

F. Analytical Tools, Learning and Knowledge for Scaling

Front-line staff need analytical tools, training and knowledge management support for the systematic pursuit of scaling as part of project design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. Some of the case study funders (e.g., IDB-Lab, CRS, CGIAR, GFF and USAID FTF) developed specific conceptual frameworks combined with tools to integrate scaling into intervention designs, assess scalability and monitor progress or used existing tools such as the Management Systems International (MSI) Scalability Assessment tool. Some also put in place training modules for scaling as part of their standard staff training (e.g., IFAD, CGIAR and CRS) or grantees’ training facilities (e.g., USAID FTF). So far, none of the case study funders included consultants and local counterpart teams in their scaling training. Since these actors often play a key role in supporting funders’ frontline teams, conducting ecosystem assessments and design, training them in scaling can be critical to successful mainstreaming.

Some funders developed systematic knowledge management activities and products that help staff pursue scaling. For example, IFAD prepared reports on the scaling experience and approaches in various specific areas of agriculture and rural development for its staff and published them on its website. GIZ developed a scaling framework and guidance document and is developing guidance for scaling digital innovations. Nonetheless, even in cases where internal tools and guidance have been developed, there usually remains a substantial gap between those knowledge products and tools and their widespread application and utilization. This gap reinforces the need for leadership, changes in organizational culture and incentives, and commitment of dedicated resources.

G. Monitoring and Evaluation as Drivers of Mainstreaming Scaling

In order to understand whether mainstreaming scaling is actually happening and whether it is having the desired effect in terms of achieving sustained impact at scale a systematic process of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of the mainstreaming process is required. The insights gained from such M&E would help drive mainstreaming scaling by providing evidence for accountability and learning by the leadership, governing bodies, staff, and stakeholders. However, the case studies suggest that this potential driver has not played much of role in the past nor is it being currently leveraged since the funder organizations under review have not systematically monitored or evaluated their mainstreaming process, even as they monitor and evaluate the implementation of the projects the finance. The closest we found to assessing the mainstreaming process was in GIZ and IFAD, which carried out ex-post evaluations or assessments of their scaling performance. The results of these have been informative, but they have not been major drivers of internal reforms to integrate scaling. Other case study funders do not appear to have carried out comparable evaluations.

However, even where ex-post evaluations are carried out, they generally do not consider the 10-15 year time horizon needed to determine whether the support for scaling achieved its long-term scaling goals. Only longer-term retrospective evaluations will be able to assess scaling impact. None of the funder organizations considered have conducted such an evaluation, as far as we can determine from the case studies. Such evaluations might best be conducted as cooperative efforts across multiple funder organizations since partnerships and hand-off from one to another funder are such a critical determinant of successful scaling.

H. Planning and Sequencing Mainstreaming

Each of the enabling factors or drivers presented in this section creates incentives for managers and staff to focus on scaling. For small organizations (e.g., ECF, GCC and Syngenta Foundation), concerted drives by senior leadership may be sufficient for scaling to become intrinsic to the organization. However, the enabling factors discussed above have so far not been sufficient to support the effective implementation of a mainstreaming effort in large organizations.

General commitment by senior management to pursue a mainstreaming agenda and aspirational references to scale and scaling are not sufficient in driving organizational culture change in large institutions without incentives for middle management and front-line staff. Policies and processes (including Human Resources policies and accountability), organizational and budgetary support, technical help and learning opportunities must complement clear mission statements and corporate strategies with scaling at their core. These can be amplified by strong messaging from the top leadership and backed by the governing bodies. Monitoring metrics and evaluation of mainstreaming performance and scaling impact can be additional incentives and accountability instruments for managers and teams.

In practice that means that for the larger, complex funder organization, a systematic, multi-year effort to establish the enabling conditions and incentives is required for successful mainstreaming and organizational culture and mindset change. This, in turn, requires explicit prioritization and sequencing of multiple steps towards the mainstreaming of scaling. For funders early in the mainstreaming process, the initial priority is to assure an explicit focus in mission statements strategies and workplans, clear and appropriate definitions of scale and scaling, and strong signals from top leadership. This should be accompanied by developing scaling frameworks, operational policies and processes in support of scaling; simple results metrics for monitoring and tracking progress; and training and resource people to support their utilization. For funders that are further along, the priority will likely be to (i) integrate scaling into operations, procedures, monitoring and evaluation; (ii) provide significant dedicated financial and human resources especially for front-line teams; (iii) ensure and incentivize implementation by front-line teams; and (iv) track longer-term experience with scaling to revise, refine and update their approach. The IFAD case study demonstrated how prioritization and sequencing can work well in practice, but also some of the potential pitfalls faced in implementing a long-term organizational change process in support of mainstreaming scaling. (Box 6, next page)

IV. Incorporating Good Scaling Practices into Mainstreaming

So far, we have focused on the current state of mainstreaming and on its principal enabling factors. We now consider the extent to which funders incorporate proven scaling practices into their operational approaches. Mainstreaming scaling will not be effective without mainstreaming good scaling approaches as we noted in Section I.

Perhaps the critical aspect of good scaling practice, which we already introduced in Section III as an enabling factor for mainstreaming because it is foundational for a mainstreaming effort, is the need to focus on transformative rather than merely transactional scaling. The other aspects of good scaling in effect help ensure that the scaling approach is transformational.

A. Scaling from the Beginning (“Start with the End in Mind”)

The scaling literature stresses the importance of pursuing scaling from the beginning, rather than at the end of an innovation process or project. Here the story is encouraging. The case studies suggest that many funders focus on scaling early in the innovation or project preparation process (e.g., CARE, CGIAR, CRS, GCC, IFAD, Syngenta Foundation and HarvestPlus). However, for larger funders, getting project teams, managers and quality assurance units to focus adequate attention on the scaling agenda during project preparation remains a challenge. There are simply too many other corporate priorities that they must address with limited time and resources.

B. Scalability Assessment

Scalability assessment have multiple functions: (i) to help determine whether an innovation or project is suitable for scaling; (ii) to assess what may have to be adjusted in the design of the intervention in the face of systemic constraints; and (iii) to identify accompanying system changes needed to address constraints or to put in place appropriate enabling conditions for scaling to succeed.

Some of the funders we studied recognize the need for an explicit scalability assessment and have developed and used tools to conduct such an assessment (e.g., CGIAR, GCC, IDB-Lab, CRS and CARE). CGIAR’s tool is the most advanced and complex in this regard. It requires identifying all complementary innovations relative to a core innovation, the “Innovation Package,” and conducting context, stakeholder and political economy analyses. These analyses are used to determine bottlenecks to scaling and develop actions to address those bottlenecks. GCC includes scaling potential among its general grant making criteria, and scaling is at the core of its funding instruments that target transition to scale. Some funders pay special attention to the financing constraints to sustainable scaling (e.g., GFF), while others focus more on policy and institutional strengthening (e.g., GIZ and GCC). IFAD’s scalability assessment involves a systematic consideration of enabling conditions (or “drivers and spaces”). USAID’s FTF developed a detailed guidance document on scaling, the Agricultural Scalability Assessment Tool. It is now testing a tool – “Innovation to Impact” (or i2i) – that applies criteria used by private agri-business to decide whether to invest in innovations as they move through the stages of research, development and testing, i.e., establishing what are called stage gates to decide whether to advance to the next stage of innovation and scaling.

C. Integrating Systems Change with Scaling Support

As noted above, systems change often is critical complement to scaling and scalability assessments focus on systemic constraints and the need to address them. At small scales, development funders and their projects, or implementing partners, grantees and social enterprises have sufficient resources to address obstacles to successful implementation, results and impact. However, scaling to the size of the problem, especially if that scale is national and regional, inevitably encounters systemic obstacles that can severely constrain or prevent scaling. National public policy, legal and regulatory environments are obvious examples, along with the implementation capacity of potential public or private sector Doers, and with the availability of fiscal space if the public sector is the Payer. Because the resources involved at large scale are so much greater, scaling inevitably becomes a political economy question and the interests of many stakeholders are implicated and must be addressed. The same can be true with social norms and beliefs. Addressing some or all of these issues can be essential to successful scaling, which means that they need to be included in mainstreaming. System change may also affect the demand for an innovation (positively or negatively) and this affect the scope for scaling, e.g., when tax or subsidy policies change and affect demand for a public or private service.

Most large official funders support systems change. GIZ, for example, both helps build capacity and change the public sector enabling environment. However, very few larger organizations in our sample coordinate their investments in systems change with the needs of scaling, GFF and IFAD excepted. Integrating systems change is particularly a challenge for smaller funders and those working on innovation, as their mandate is to focus on the innovation, and not the system. Nonetheless, GCC and the CGIAR have taken steps to integrate systems change, as far as possible with their limited resources. The CGIAR strengthens national agricultural research and extension services and provides policy advice. GCC launched pilot efforts to help health officials identify and prioritize scaling needs.

The relationship between scaling and systems change once again reinforces the need for effective partnerships for scaling, in this case with organizations that invest in systems strengthening. Among small funders, Syngenta Foundation has arguably done the most in developing systems change partnership, as demonstrated by their SEEDS2B program (Box 7). However, this example also demonstrates the challenges for funders even when there are willing partners ready to support scaling with systems change.

D. Equity and Inclusion

Most of the funders specifically include equity and inclusion objectives in their efforts to pursue scaling, whether it is small-holders farmers in general (e.g., Syngenta) or in remote areas (e.g., IFAD), farmers overall (e.g., CGIAR), or women and children (e.g., GFF), or other equity and inclusion targets. CARE puts gender and gender equity at the center of its work. One of CRS’s scaling principles is to: “Engage with systems actors, both traditionally underrepresented and existing decision-makers, to prioritize equitable scaling.” However, the explicit consideration of the potential tension between scale and equity and inclusion received less attention in our sample. Also not explicitly considered is the fact that scaling typically results in losers as well as winners, and in a variety of unintended consequences. Thus, there are often implicit and unacknowledged tradeoffs between equity and scale (see Section V: Challenges, Tradeoffs and Tensions).

E. Country Ownership and Localization

The pursuit and achievement of sustainable impact at scale requires country ownership of the goals and interventions supported by funders. More broadly, what is now often referred to as “localization” provides an important underpinning for effective and sustainable scaling. This includes broad stakeholder engagement; creation of demand for innovative solutions; market development; support for and use of local capacity and systems; and preparing for effective hand-off at project or program end to national organizations. By way of example, GFF supported the development of inclusive country platforms for maternal and child health programs. These platforms bring together an array of national stakeholders, including concerned government ministries and representatives from the private sector and civil society, to jointly develop a sector strategy, implementation modalities, results tracking approach and MEAL activities.

A growing number of our agricultural cases showed a shift from supply to demand-driven scaling, which requires engagement and ownership by local input producers, farmers, processors and consumers. Syngenta Foundation, in its SEEDS2B work with local farmers, seed companies and other parts of the seed value chain, creates target product profiles based on local market research. HarvestPlus works with stakeholders across all stages of the innovation-to-scale pathway for biofortified foods, including researchers, seed producers, farmers, food processors and distributors, and ultimately retailers and consumers.

While many funders preach the benefits of national ownership and localization, many face challenges in implementing their good intentions. Challenges are especially severe for larger official funders because their leaderships, parliaments and ultimately the taxpayers find it difficult to give up control over their individual priorities.

Staff and managers in some funder organizations also noted that national ownership, while necessary for long-term sustainable scaling, is no guarantee for success. National priorities may shift unpredictably with election cycles, government overhauls and economic and social crises, disrupting the best-laid scaling plans. These shifts put a premium on funders’ abilities to maintain support in a manner that respects national priorities but also allows the core elements of a scaling strategy to remain in place. Moreover, multi-stakeholder engagement requires an ongoing country presence and long-term relationships that are difficult to create or maintain when work on the ground is project-by-project and supported from abroad with intermittent expert visits. CRS mitigates these risks by engaging with multiple stakeholders on the ground, especially market and civil society actors, so that support remains even when governments and their policies change.

Finally, as noted in Section III above, many funders, especially the larger ones, have pursued decentralization of their operational staff to national or regional offices, closer to the clients. This in principle should help with generating local ownership, building partnerships on the ground, and monitoring progress in and constraints to scaling innovations and projects. As such it should support localization and also scaling. However, experience shows, including from the case studies, that decentralization alone does not necessarily mean stronger localization or better scaling. Much depends on whether the many other enabling factors and good scaling practices are effectively established through the funder organization and effectively driven into front line decision making. As noted in Section III, decentralization can actually make it more difficult to achieve some aspects of scaling due to greater institutional distance between headquarter and country office.

F. Partnerships with Other Funders

Aside from the need to support domestic stakeholder platforms for the joint and sustained pursuit of a scaling strategy, international funders also need to coordinate and cooperate with one another in the often highly fragmented development assistance architecture.

The funders in our case studies universally recognize the need for partnerships as a key element for achieving impact at scale. HarvestPlus puts partnerships at the center of its work and approach. As such, HarvestPlus invested substantial resources in its internal capacity to create and manage partnerships. USAID’s FTF created an Office for Market and Partnerships to facilitate partnerships with other funders. However, in the case of FTF, the office has few staff and an extremely limited budget. The CGIAR recognized the need for greater partnership internal capacity and developed a strategy for this. But, the strategy has not yet been implemented. IFAD defined scaling as working with other partners to increase impact.

However, many funder partnerships are one-off creations by implementing partners for particular projects and hence commitment to achieving transformational, rather than transactional partnerships remains limited. Transformational partnerships allow effective cooperation and potential hand-off from one partner to another, and ultimately to organizations able to deliver and fund goods and services on a sustainable basis at scale. In contrast, transactional partnerships simply represent cooperation or cofinancing for a larger one-off project without a longer-term strategy for sustainable scale. In other words, most funders find it relatively easy to organize partnerships with other funders to expand the size of a particular intervention or project and the resource dedicated to it through cofinancing or parallel financing. It is much more challenging to identify partners to hand-off to (i.e., longitudinal partnerships) and to involve these partners early on in project preparation and implementation with a view to their longer-term engagement beyond project end. Of course, ultimately the most important – and most frequently neglected – hand-off comes when external funders exit and local government and/or private funders and operators have to step in to sustain the scaling process or operation at scale.