Executive summary

The Standards and Trade Development Facility (STDF) is a global partnership that promotes improved food safety and animal and plant health in developing countries. STDF helps developing countries meet sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) requirements for imports and exports, based on international standards. It acts through three interlinked workstreams — Global Platform, Knowledge Work, and the Grant Mechanism — to catalyse change by convening, innovating, and learning for effective SPS practices. STDF is supported by donor contributions from Australia, Canada, European Union, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the United States.

This report explores what it would mean for the STDF to engage with scaling more intentionally (i.e. to mainstream scaling). It addresses: what the partnership is already doing that supports uptake and influence, where gaps or missed opportunities exist, and what strategic and operational adjustments could increase its ability to operate more effectively at scale.

How scaling works across the workstreams

The STDF already is doing a lot of scaling work, reflecting its focus on catalysing, even if it has not historically been framed as “scaling”. The STDF’s 2025-2030 Strategy now gives it a strong, explicit scaling mandate. Through this report and other ongoing efforts, STDF is now identifying how it will operationalize scaling for improved results and reach.

Grant Mechanism: Demand-driven projects and project preparation grants already contain processes supportive of scaling, including co-financing requirements and multi-stakeholder alignment. Scalability is discussed during grant review processes, but there is not a common understanding of what this means in practice. Explicit scaling pathways and post-grant handoffs could improve scaling outcomes.

Knowledge Work: Tools and guidance are designed for adaptation and adoption across developing countries and targeted dissemination activities occur. However, knowledge products or guidance on how to scale could improve scaling outcomes.

Global Platform: The STDF’s convening power creates the space for networking and partnership to scale, but it does not consistently use its influence to facilitate strategic handoff for scale. Systematic follow-up on identified synergies and handoff opportunities could improve scaling outcomes.

Enablers and characteristics of mainstreaming scaling

The Scaling Community of Practice’s Mainstreaming Tracker Tool was used to organize the analysis on how scaling has been mainstreamed within the STDF.

Vision, goals, and strategy: The STDF’s vision, goals, and strategy are aligned with scaling goals. Since 2015 (and with increased focus since 2020), the STDF positioned itself as a catalyst of change and safe trade facilitation. Further clarity about the extent to which it focuses on generating knowledge for others to act on through improved practices vs. directly implementing projects that improve outcomes could improve scaling outcomes.

Definition of and common language for scaling: There is no common definition of scaling within the STDF. However, terms like sustainability and spillovers are well understood, widely used, and capture

many concepts related to scaling. A common understanding of scaling could make consistent prioritization of scaling easier and improve scaling outcomes. The STDF may wish to consider the following definition of scaling: facilitating the adoption, expansion, and sustainability of successful SPS solutions so that they meaningfully reduce unsafe trade beyond the STDF Secretariat’s direct support.

Culture, incentives, and measures of success: The STDF’s prioritization of collaborative support and trust-building are likely to lay a strong foundation for partnership-based scaling. However, there is a widespread view that, because scaling relies heavily on external stakeholders, scaling is outside the control of the STDF Working Group and Secretariat. Furthermore, many believe that, if everything cannot be scaled, it should not be prioritized. However, these arguments do not necessarily mean that scaling should not be prioritized at all, only that it should be rationally prioritized. Incentives for staff, grantees, and Working Group members to support scaling, supported by defined measures of success, could provide clarity about how scaling can be rationally prioritized, induce a cultural shift, and improve scaling outcomes.

Partnership and intermediary function: Because the STDF is a catalytic partnership, the partnership and intermediary function is the STDF’s strongest asset in supporting scaling. Much of the STDF’s work, particularly its Global Platform, create the space for networking and intermediation, which support scaling and handoff. However, there is a widespread assumption among some within the partnership that successful projects will scale themselves. The STDF could actively use its influence and connections to facilitate and manage transition processes to improve scaling outcomes.

Instruments, policies, and processes: While several previous STDF strategies addressed STDF’s “catalysing” role, scaling has not been a historical goal of the STDF and the STDF has not developed dedicated policies or processes to support scaling. However, this does not mean that its policies and processes do not support scaling. STDF Knowledge Work can support scaling by being intentionally designed for easy adaptation and adoption across low-resource contexts. Its Global Platform supports the dissemination of good practices, which can enable vertical scaling. The demand driven nature of STDF Grant Mechanism is often viewed as a barrier to selection for scaling; however, scalability could be used as an assessment criteria and the STDF could engage in late-stage co-design for scaling to improve scaling outcomes.

Dedicated resources for scaling: The STDF is starting to dedicate resources for scaling; largely in the context of innovation and scaling activities. This case study also represents a key investment in scaling for the STDF. Nonetheless, scaling will likely need to be resourced and specifically integrated into the annual STDF workplan (approved by the Working Group), as well as workplans of the STDF Secretariat, including project managers, to improve scaling outcomes.

Analytical frameworks, tools, and knowledge: Although the STDF’s Knowledge Work is designed for scaling, the STDF does not have specific frameworks and tools to facilitate scaling. It could create guides for grantees or project managers on designing for scale or scalability assessments to improve scaling outcomes (Appendix 2).

Integration into monitoring, evaluation, and learning: The STDF already has many indicators for scaling in its MEL framework. Its systematic data collection from grantees gives it the opportunity to conduct cross-project analysis to determine the types of projects that get scaled. Collecting data over much longer timeframes (10+ years) could provide the necessary information to fully capture the scaling journey of its projects and allow for evidence-based decision-making about the types of grants that will scale to improve scaling outcomes.

Constraints, challenges, and opportunities

The STDF’s efforts to mainstream scaling may be constrained by its ad hoc approach to scaling, lack of a common language, dependency on internal and external stakeholders, small Secretariat, limited resources, decentralized governance structure, and lack of current capacity to assess scaling and scalability. These constraints do not mean that the STDF cannot prioritize scaling, only that it will need to mitigate these constraints or develop strategies that function within them. In doing so, the STDF will need to manage its institutional capacity and incentives, interactions with its Working Group for scaling and handoff, MEL, and engagement with the external environment

A number specific change opportunities were identified for the STDF as outlined below. These include both incremental and transformative opportunities for the short, medium and longer term. More details are provided in a Table at the end of the executive summary.

Define “scaling” and use the definition end-to-end. Adopt an internally owned definition that distinguishes scaling from sustainability and set expectations for horizontal, vertical, and deepening scaling. Embed the definition across concept notes, review criteria, closeout, and MEL to facilitate discussions about STDF’s priorities.

Resource the partnership and intermediation function. Make brokering, alignment, and handoff a deliberate STDF role. Specify process, assign responsibility, and formalize partner pathways for post-grant uptake.

Turn the Working Group into a systematic handoff engine. Ask members to assess alignment with their programmes at approval and to lead specific post-grant actions on a volunteer basis based on mutual benefit. Track handoffs (who, what, by when) and use closeout sessions to name and empower a “scale sponsor.”

Move partner engagement earlier. Start donor and implementer engagement during implementation, not at closeout. Pilot a light, time-bound bridge (6–12 months) to support a post-grant champion for a small number of high-potential projects.

Grant application process and implementation for “fit to scale.” Add screening criteria based on supply-chain relevance, donor fit, beneficiary credibility, and communications, which were perceived to drive scalability of projects within the STDF. However, do not adopt rigid expectations that all grants meet these criteria; set attainable targets. Engage in late-stage co-design to increase the scalability of promising projects. Use project preparation grants and mid-term reviews to de-risk scale-pathways.

Update MEL to track uptake, not just outputs. Define a small set of comparable scale indicators (e.g., adoption/replication, institutional embedding, follow-on finance) and configure monitoring processes to aggregate them. Develop a simple post-grant repository to record uptake, financing, and policy effects.

Align culture and incentives. Make scaling someone’s job. Clarify Secretariat, Working Group, and grantee roles. Integrate dedicated action for handoffs into project manager workplans and set realistic expectations for scaling. Reward learning and credible handoffs, not just completion.

Summary of identified change opportunities

| Opportunity | Work stream | Stakeholder | Timeframe | Ease of implementation | Impact on mainstreaming |

| Incremental change opportunities | |||||

| Continue knowledge management efforts to improve accessibility and address challenges stakeholders face in finding existing Knowledge Work outputs. | Knowledge Work | Secretariat | Short-term | Easy | Minor |

| Implementing partners leverage their own networks to facilitate the transition to scale. | Grant Mechanism | Implementing partners | Short-term | Easy | Minor to Moderate |

| Develop STDF’s own definition of scaling and specify the extent of its ambition and expectations for internal and external stakeholders. | Crosscutting | Secretariat, with input from Working Group | Short-term | Easy | Moderate |

| Use consistent terminology for projects/pilots and apply the four characteristics of scalable projects to prioritize funding. | Grant Mechanism | Secretariat, Working Group | Short-term | Easy | Moderate |

| Integrate transformational scaling indicators into the new Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) framework. | Crosscutting | Secretariat, with input from Working Group | Short-term | Moderate | Moderate |

| Working Group members proactively identify and advocate for projects their organization would be interested in scaling; ensure systematic follow-up on identified synergies by the Secretariat. | Grant Mechanism, Global Platform | Working Group, Secretariat | Medium-term | Moderate | Moderate |

| Grantees use some of their budget for continuous donor engagement throughout the project lifecycle. | Grant Mechanism | Grantees, with support from Secretariat and Working Group | Medium-term | Moderate | Moderate |

| Invest in developing scaling guidance for both grantees and staff, including tools to design projects for scale and resources for staff capacity building in scaling strategy. | Crosscutting | Secretariat | Medium-term | Moderate | Moderate |

| Leverage existing data for cross-project comparisons and follow projects over longer timeframes to identify characteristics of projects that tend to scale. | Grant Mechanism | Secretariat | Medium-term | Moderate | Moderate |

| Explore impact evaluation approaches assess STDF’s impact at scale. | Grant Mechanism | Secretariat | Medium-term | Moderate | Moderate |

| Specify which types of grants and activities should be designed for scale and clearly articulate reasons for pursuing activities unlikely to scale. | Crosscutting | Secretariat, Working Group | Medium-term | Moderate | Moderate |

| Transformational change opportunities | |||||

| Set realistic targets for the percentage of project grants and Knowledge Work outputs designed to scale, and the percentage that ultimately achieve scale. | Grant Mechanism, Knowledge Work | Working Group | Medium-term | Easy | Significant |

| Invest in staff training and time to support scaling. | Crosscutting | Secretariat | Medium-term | Moderate | Significant |

| Consider dedicated funding for the transition to scale. | Grant Mechanism | Working Group | Medium-term | Difficult | Significant |

| Formalize the intermediary role by creating partnerships with implementing organizations for matchmaking, hiring external consultants, or identifying dedicated STDF staff. This requires dedicated funding. | Crosscutting | Secretariat, with input from Working Group | Long-term | Difficult | Significant |

| Adopt a formal expectation that Working Group members consider integrating successful pilots into their programmes, particularly for projects they advocated for. | Grant Mechanism | Working Group | Long-term | Difficult | Significant |

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE

Scaling definitions

Horizontal scaling: Scaling to new locations, places, populations, and institutions. Often referred to as replication; however, horizontal scaling can also be adaptive.

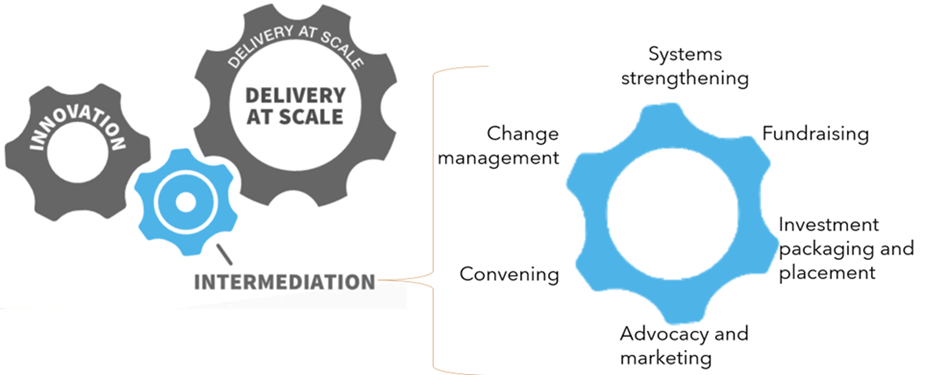

Intermediary: An entity that bridges the gap between innovation and large-scale adoption, facilitating connections between innovators, implementers, funders, and national systems.

Mainstreaming scaling: The deliberate and systematic integration of a focus on achieving sustainable impact at scale across all facets of an organization’s operations and work streams.

Scale: Sustainable impact that addresses a significant share of the global, regional, or national problem.

Scaling: A process of achieving sustainable impact that meaningfully addresses a significant share of the global, regional, or national problem.

Scaling Deep: Changing underlying values, behaviours, relationships, to ensure meaningful, lasting impact.

Sustainability: The ability of an activity to continue to improve outcomes after the grant period ends.

Transition to scale: After approaches have been proven successful in limited contexts, they need to undergo a targeted refinement and investment process to prepare for broader uptake. This often involves establishing additional partnerships, securing more funding, and modifying approaches to be more versatile.

Vertical scaling: Embedding in and changing large scale (often national) systems, e.g. policy reform, changes to the policy enabling environment, or market systems. Vertical scaling can also refer to institutionalization.

Acronyms

| CABI | Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International |

| CODEX | Codex Alimentarius Commission |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| AU-IAPSC | African Union Inter-African Phytosanitary Council |

| IPPC | International Plant Protection Convention |

| KEPHIS | Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Services |

| LDCs | Least developed countries |

| LMICs | Lower middle-income countries |

| MEL | Monitoring, evaluation, and learning |

| SPS | Sanitary and phytosanitary |

| SCoP | Scaling Community of Practice |

| SADC | Southern African Development Community |

| STDF | Standards and Trade Development Facility |

| UMICs | Upper middle-income countries |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WOAH | World Organisation for Animal Health |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

Introduction

Across the development sector, there is a growing consensus that one-off, small, well-executed projects are not sufficient to meet the needs of international development. Solving complex global, regional, or national problems requires development actors to think and operate at scale. The challenge is not simply how to innovate, but how to enable effective solutions to spread, embed, and endure. In this context, scaling has shifted from a technical consideration to a strategic imperative.

The Scaling Community of Practice (SCoP) facilitates knowledge exchange among practitioners for scaling, develops standards and knowledge products for scaling, and supports organizations adopting a scaling mindset. It champions the concept of mainstreaming scaling — embedding the capacity and commitment to scale into institutional operations. Rather than treating scaling as the responsibility of individual grantees or isolated champions, mainstreaming is the deliberate and systematic focus on achieving sustainable impact at scale across all facets of an organization’s operations and work streams. This report is part of a broader series of SCoP-supported case studies that examine how different groups mainstream scaling in practice.

One of the most consistent findings across the SCoP’s work is that scaling rarely happens by accident.1 When successful innovations scale, it is often because an institution deliberately created enabling conditions through its project or grant design criteria, its approach to partnerships, its use of data, or the expectations it sets for staff and grantees. However, many organizations that aspire to achieve impact at scale have not yet translated that aspiration into internal systems. As a result, scaling approaches often remain informal, inconsistent, and dependent on individual initiative rather than institutional intent.

Given the recent publication of the Standards and Trade Development Facility (STDF)’s Strategy 2025 -2030,2 which repeatedly references scaling, the STDF case study offers a timely and instructive perspective on scaling. With a mandate to support safe trade facilitation through improved and sustained sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) of public and private sector stakeholders and a long-standing role in piloting and disseminating promising approaches, the STDF already operates at scale in many ways. It achieves outsized results for its budget, partially because of its focus on influence and catalysing change as opposed to being the change.3 Before the publication of the new strategy, the STDF did so without explicitly framing its contribution as scaling or building mechanisms to systematically enable scaling. However, the STDF is now considering how to better approach and operationalize scaling for greater results and impacts.

This report explores what it would mean for the STDF to engage with scaling more intentionally: what the partnership is already doing that supports uptake and influence, where gaps or missed opportunities exist, and what strategic and operational adjustments could increase its ability to operate more effectively at scale. The goal is not to critique past choices, many of which reflect deliberate priorities in a different strategic context, nor to increase staff size or resources, but to offer insight into opportunities that could respond to scaling as a specific objective. Because the STDF has not historically framed its work around scaling, identified gaps should not be viewed as shortcomings, but as entry points for scaling impact. The analysis is meant to support learning and inform decision-making if the STDF chooses to deepen its engagement with scaling. In doing so, it contributes to a broader conversation about how catalytic groups with limited resources can support long-term, scalable impact.

Background on the STDF

The STDF is a global partnership that promotes improved food safety and animal and plant health in developing countries. This helps developing countries meet sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) requirements for imports and exports, based on international standards. Meeting these standards is necessary for participation in international agricultural trade.

The partnership was founded by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), World Bank, World Health Organization (WHO), World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), and the World Trade Organization (WTO).2 It also includes representatives from the Secretariats of the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CODEX) and the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC), as well as donor representatives, selected developing country experts, and other international, regional, and private sector organizations involved in SPS capacity development.

The STDF is composed of three main groups: the Policy Committee, the Working Group, and the Secretariat.2 The Policy Committee is the governing and oversight body. It approved the recently updated 2025-2030 Strategy, which repeatedly references scaling. Through the Policy Committee, high-level representatives of STDF’s founding partners, donors, and developing country experts decide on STDF policy and strategy. The Working Group is composed of technical representatives of the STDF’s founding partners, donors, developing country experts, and the Secretariats of the CODEX and IPPC, as well as other organizations. The Working Group approves the STDF’s workplan, decides which knowledge work and grants to pursue, oversees and contributes to ongoing STDF work on knowledge topics, and guides the allocation of resources. It also serves as a platform for knowledge exchange and learning among members. Finally, the Secretariat is housed within the WTO and delivers the STDF workplan. While the Policy Committee and Working Group are composed of people from other organizations (and the WTO) supporting the STDF as a small part of their workplans, the Secretariat has nine fulltime staff and one or two temporary employees, such as interns and young professionals.

The STDF has three integrated workstreams: the Global Platform, Knowledge Work, and Grant Mechanism.3 Workstreams are not distinct or siloed and most activities function across the workstreams. In its most limited sense, the Global Platform is the STDF’s Working Group and Practitioner Groups. However, it is often conceptualized as the full network that enables and facilitates the dissemination of STDF good practices to influence the work of other stakeholders. In this context, it includes all networking, dissemination, and influencing work conducted by the STDF. The STDF manages various sector, thematic, and regional learning groups and networks. The Global Platform promotes a coherent approach to collaboration on safe trade and SPS capacity development.

Through the STDF’s Knowledge Work, the STDF creates tools, resources, and guidance to support SPS capacity development and safe trade facilitation. These include information to support public-private partnerships, SPS capacity development prioritization, digital tools, and good regulatory practices. The STDF prioritizes Knowledge Work related to gender and the environment. Knowledge Work emphasizes dissemination through the Global Platform.

Finally, the STDF has a Grant Mechanism to bring together public, private, and other actors at the global, regional, and national levels to pilot innovative and collaborative approaches, leverage expertise, and deliver results for SPS capacity building and safe trade facilitation. Grants are demand driven; calls for specific types of applications are not conducted. The Secretariat reviews grants on a rolling basis and brings them for review by the Working Group twice a year. The STDF supports an average of six project grants per year with up to USD 1 million and six project preparation grants with up to USD 50,000 per grant. Project grants are generally three years, but project preparation grants are limited to about one year. Recipients of project grants must provide matching monetary or in-kind contributions on a sliding

scale based on the development status of their country. They are also encouraged to mobilize additional external funding.

As a partnership and networking group, the STDF also formally acknowledges other members as part of its structure.3 These include other United Nations agencies, inter-governmental organizations, regional organizations, and the private sector. Through its Global Platform function, the STDF’s various learning groups and networks inform the STDF’s strategic and programming decisions.

History of scaling

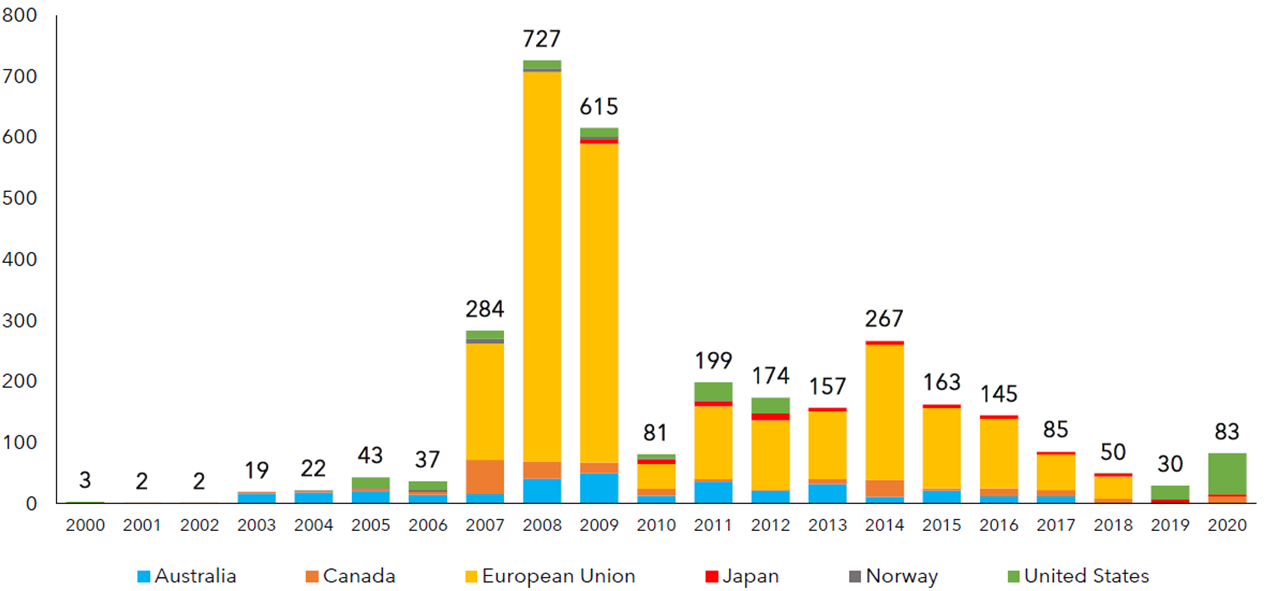

At its core, the STDF is a scaling partnership: it aims to “catalyse change” to facilitate safe trade to regional and global markets, that aligns to the international standards for food safety (Codex), animal health (WOAH), and plant health (IPPC) SPS standards recognized in the WTO SPS Agreement. Despite not taking a systematic approach to scaling in the past, the STDF has been a de facto scaling champion. For the most part, it does not try to fund or implement transformative change itself. The partnership has correctly concluded that its limited budget prevents it from being able to fundamentally change global trade structures on its own. Based on reporting to the WTO SPS Committee, the STDF’s annual budget over the last 20 years has been relatively insignificant compared to funding provided bilaterally for SPS technical assistance.

Figure 1: Bilateral SPS technical assistance (in USD millions)

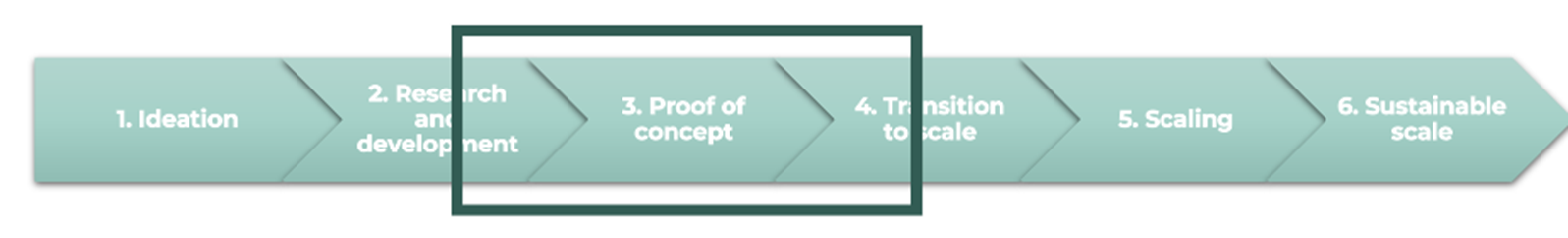

In light of this, the STDF focuses on providing tools and supporting capacity building for developing countries to change their own trade dynamics. The STDF has positioned itself to work in the central portion of the scaling pathway (Figure 1). This pathway outlines how innovations generally start as ideas, which must undergo extensive research and development before being proven to work at a small scale. These proven technologies then undergo a transition process with targeted refinement and investment to make them appropriate for scaling before they can operate at a sustainable scale.

The STDF generally supports country governments, and to a lesser extent private sector actors, with proof-of-concept pilots and knowledge pieces. However, some of the STDF’s Grants and Knowledge Work include a limited amount of research and development, and it passively supports the transition to scale through its Global Platform. Targeted support for handoff to the next funder and capacity building for scaling are limited.

Figure 2: STDF’s position on the pathway to scale.

The term “scaling” has been somewhat familiar to the STDF Secretariat and Working Group members for years as part of the general dialogue in international development. However, it is unclear how long the STDF itself has been thinking about scaling. Some interview participants claimed that the partnership has always thought about scaling and others believed scaling was a new topic. This confusion is likely rooted in the lack of a common understanding of scaling and the STDF’s longstanding focus on sustainability, catalysing change, and spillover effects on other organizations. All these concepts include components of scaling. Some interview participants seemed to consider the STDF’s focus on these to reflect a focus on scaling, while others did not.

“In many ways, the STDF is a huge juggernaut of scaling, with the partnership work in the different workstreams”

Interviewer: “Where is this discussion of scaling coming from?”

Respondent: “No idea”

While the STDF has often facilitated scaling outcomes, references to scaling in partnership documents have historically been limited. Before the new Strategy, scaling appeared occasionally in annual reports and in the Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) framework, but was not a priority. Nonetheless, scaling activities emerged organically due to other organizational priorities. Much of the STDF’s work focuses on vertical scaling, embedding new approaches into national or international system, as opposed to horizontal scaling, replicating new approaches in different areas; although, it supports both.

The 2024 external evaluation5 marked a turning point. It concluded that the STDF achieves results and influence beyond what would typically be expected for its modest budget and that scaling was a key enabler of this outsized impact. Donors and Working Group members viewed this finding as a key point of leverage for the next strategy.

“Key enablers include the network and the role of the developing country experts especially; the ability to pilot and successfully scale up innovative approaches; the capacity to broadcast and promote uptake of knowledge products; and the established programme management capacity to support and oversee the delivery of a sizeable portfolio of technically challenging projects across the world. The barriers to achieving the programmatic objectives relate to the scale of STDF, the demand-driven nature of project development, and the capacity of STDF to deliver outreach.”5

These findings motivated the STDF’s current engagement with scaling. Scaling now appears repeatedly in the 2025-2030 strategy3 and the 2025 workplan. However, the partnership is still determining if, and how, it wants to institutionalize and operationalize its commitment to scaling. The STDF could choose to leave scaling as a general principle or move along a continuum towards a formal, mainstreamed approach that shapes its processes, measurement systems, and institutional culture. This case study will serve as one input into that decision.

Methods

This case study relied predominantly on publicly available documents provided by the STDF Secretariat outlining their current and historical approaches, policies, practices, and projects and interviews with a selected set of key stakeholders. The STDF provided 32 documents to review (Appendix table A1). These documents broadly related to STDF grant processes, STDF published results and evaluations, STDF Knowledge Work, and STDF strategy and operational approaches. Between June 23rd and August 12th 2025, 14 interviews were conducted. Several interviews included multiple participants, resulting in a total of 22 people being interviewed. The researcher also attended the June 2025 Working Group meeting as an observer to understand the group’s dynamics.

Interview transcripts, interview notes, and documents prioritized for detailed document review were coded in qualitative software (Appendix 1). During coding, notes were also kept in an online document shared with the STDF Secretariat and senior experts within the SCoP. They gave feedback on interim findings, suggested additional areas of inquiry, offered clarifications, and provided interpretive insights. Notes and the coded dataset were then reviewed and synthesized narratively for this report. Responses were anonymized to encourage sharing of differing perspectives.

The remainder of the report presents how scaling works across the STDF’s workstreams and analyses the STDF’s approach to mainstreaming scaling based on the SCoP’s Mainstreaming Tracker Tool.6 After the main analysis, a section is dedicated to the consideration of constraints, challenges, and opportunities for the STDF. This includes a set of concrete change opportunities for the STDF, should the Working Group decide to mainstream scaling. Change opportunities are purposefully split into incremental change opportunities and transformational change opportunities to differentiate between those that could be taken without significantly changing the partnership and more fundamental change opportunities which might be more difficult to achieve but have broader effects. The report closes with lessons that could be applied to the broader community of international development actors.

Scaling across STDF’s workstreams

All three of the STDF’s workstreams include operational elements that support scaling, as well as those that limit scaling. These operational elements affect the STDF’s potential opportunities to mainstream scaling.

The Grant Mechanism funds demand-driven projects that reflect national interests. However, the depth of this demand and country ownership is variable. To increase ownership and ensure support, all grants require mandatory co-financing from the grant recipient. Although the grant application process does not include a specific question on scaling, it includes questions that are directly related to scaling. These include questions about:

- How the project addresses regional challenges.

- The involvement of other stakeholders in the development of the grant, with specific probes related to government involvement and the need for all relevant ministries to provide support.

- The availability of funding from other sources, including whether funding from other sources was sought

- Complementarity with other projects both within and outside the STDF.

Project preparation grants are designed to support scaling and align with emerging best practices in the scaling field. These grants can be used to support project feasibility studies, the development of high-quality proposals for STDF funding or other funding sources, or the systematic prioritization of SPS capacities. Almost half of STDF’s project preparation grants went on to become STDF project grants and about one third went on to be funded by other donors. This suggests success in the early part of the scaling pathway, transition from ideation, research, and development to proof of concept.

STDF project grants aim to strengthen capacity to meet international standards (CODEX, IPPC, WOAH) and facilitate safe trade. Grants are meant to develop, implement, and learn from innovative, scalable pilots to deliver safe trade solutions at the global level. According to the STDF’s Operational Rules, projects are rated highly for funding if they focus on identifying, developing, and disseminating good practices through multi-country, collaborative, and interdisciplinary approaches.7 The use of outputs of STDF Knowledge Work in the design or implementation of projects is encouraged. This suggests coherence and the scaling of the Knowledge Work. The perceived long-term sustainability of projects is considered in their review for funding. Despite consistent terminology around piloting projects, there are differing perspectives within the STDF as to whether or not project grants are primarily intended to test innovative solutions or to respond to immediate SPS needs. While not mutually exclusive, these two goals can come into conflict because testing innovative solutions often requires additional inputs and is associated with higher risk than tried-and-true methods to respond to immediate needs. Generally, STDF engagement ends at the end of grants; however, grantees are asked to report on sustainability plans in their progress and final reports. Two projects a year are reviewed two-years after their closure to determine medium-term impacts.

“We are doing this piloting,….. then what after we’re done? Whose gonna take care of that platform? How’s that gonna work”

The STDF’s Knowledge Work combines activity funding with external expertise to determine what works well (and less well) for safe trade facilitation and disseminates these lessons through Practitioner Groups, events with partners, and other avenues to influence change. Much of the STDFs Knowledge Work focuses on increasing the reach and uptake of existing guidance and materials as well as cross-cutting topics like public-private partnership, good regulatory practices, evidence-based approaches, digitalization and e-certification, gender, and environment mainstreaming. The STDF supports a limited amount of basic science research, focusing more on developing knowledge products that can be easily adapted and adopted by other organizations and governments, leading to broad, systemic change. In this way, STDF prioritizes the development of transformative capacity and helping other organizations scale, as opposed to directly implementing projects at a large scale.

The Global Platform is a key pathway for the dissemination and scaling of Knowledge Work and successful grants. It aims to convene and connect stakeholders to build dialogue, drive synergies and create a collaborative eco-system for safe trade facilitation. The STDF’s position as an honest, third-party information broker is perceived to facilitate governments and other organizations adopting, adapting, and scaling lessons from other STDF workstreams.5 Bilateral conversations and leadership are thought to influence other stakeholders in the field. In this way, the STDF functions as an intermediary, providing the enabling environment that is necessary for other organizations to scale projects, but not directly funding or implementing scaling itself.

As part of the Global Platform, the Working Group has a wide range of tasks, one of which is to meet twice a year to oversee STDF work. This includes approving new grants, selecting completed projects for external ex-post evaluations, considering findings and lessons of completed evaluations, and guiding knowledge work. During their review process for new applications, Working Group members often find linkages with their own work, the work of their organization, or the work of their grantees. Many Working Group members offer to facilitate introductions, which can be very useful for scaling when they occur. However, according to interviews, follow-up between Working Group members and the Secretariat is inconsistent. There has been some suggestion that Working Group members could be a key pathway to scale by funding successful STDF projects that align with their organizational priorities. This has been done in a few cases, but Working Group members do not systematically approach project closeout presentations with an eye towards finding promising projects to scale.

The STDF’s project closeout process links to and interacts with STDF’s Knowledge Work and Global Platform. As part of grant completion, projects are expected to submit an end-of-project report, submit to an independent end of project assessment, and host a project completion workshop. The end-of-project reports can include (often implicit) references to scaling in their sections on Sustainability and Follow-up (see quote for an example). Similarly, the Sustainability and Other Unexpected Results sections of the end-of-projects assessments sometimes reference scaling directly or indirectly. Because end-of-project reports and assessments are written at project closeout, the Sustainability sections of project assessments often consider opportunities for scale, rather than reporting on scaling that has occurred.

“FAO is implementing another project that will not only support the domestication process in Zimbabwe but also promote the use of biopesticides. This, therefore, means that the SADC project has set in motion more work that will be sustained in the future.” 8

Scaling of STDF projects

STDF projects report contributing to 30 pieces of SPS legislation, regulations, policies, strategies, structures, and processes since 2020.5,

The size of STDF grant funds does not seem to be directly related to scaling.5, Rather, the ability to communicate results effectively and position projects within networks are determinants of scaling.5 Stakeholders interviewed for this work identified four additional factors they thought made projects more likely to scale:

- Activities need to be innovative and successful to scale. However, projects that are too innovative might take a long time to establish additional buy-in and be difficult to scale.

- Activities should be relevant to local supply chains, support existing exports, and solve local problems. Activities that try to develop new supply chains or exports might experience additional challenges to scale.

- Activities should align with donor priorities, either supporting value chains that have been prioritized by donor’s development support strategies or addressing specific SPS concerns of donors.

- Beneficiaries need to be effective and advocate for themselves to build on achievements after the initial grant period.

In the remainder of this section, we discuss three STDF activities that reached scaled to varying degrees: ePhyto, P-IMA, and the Centre for Phytosanitary Excellence.

| TESTIMONIALS OF STDF SCALED PROJECTS

The Good SPS Practices Guide that was developed in 2020 is becoming a national and international reference for the Penja Pepper Sector. Overall, this project remains a model and an example for the emergence and professionalization of the Penja pepper sector. Penja Pepper Geographical Indication Group (IGPP), 2020 Annual Report The pilot is an important milestone for a fully traceable livestock value chain. The Ministry of Food Agriculture and Light industry is committed to scale up the pilot nationwide to support the government’s strategic objectives to develop export markets for meat. Jambalsterem Tumur-Uya, Agriculture and Light Industry, Mongolia, 2022 Annual Report Recognizing the important of GRPs [good regulatory practices] to cut trade costs for small businesses and drive intra-regional trade, 16 COMESA Member States endorsed a decision in December 2023 to implement GRPs in the COMESA region. This work builds on measures so that smale-scall traders can benefit more from cross-border agri-food trade. Mukayi Musarurwa, Technical Barriers to Trade Expert COMESA, 2023 Annual Report When you work with institutions like the STDF, it becomes a project that can be scaled and accelerated, which is essential in a world where diseases are spreading. Richard Duncan, CEO of the Niue Honey Company, 2023 Annual Report. |

ePhyto

The ePhyto Solution is likely the most successful and clear-cut example of scaling resulting from an STDF project. Developed to modernize the global trade of plants and plant products, ePhyto replaces traditional paper-based phytosanitary certificates with an electronic system. Paper-based phytosanitary certificates are prone to inefficiencies, delays, and fraud. Electronic certification is faster, safer, and more accessible. ePhyto is intentionally inclusive, built to accommodate the technical and financial constraints of developing countries, making it universally accessible. The ePhyto Solution has three integrated components:

- A central hub allows the secure exchange of electronic phytosanitary certificates between National Plant Protection Organizations. It supports both country-specific certificates and generic phytosanitary certificates.

- The generic ePhyto national system enables countries without their own digital infrastructure to produce, send, and receive electronic certificates.

- Its harmonized data structure ensures interoperability between national and generic systems.

The STDF provided the foundational support for ePhyto, investing USD 1.1 million from 2016 to 2020. The project, implemented by IPPC, was guided by a wide-ranging partnership of 31 organizations, coordinated through a Project Steering Group, Advisory Committee, and Industry Advisory Group. Use of the central hub for the exchange of ePhyto certificates expanded rapidly.9 The generic ePhyto national system was originally piloted in Sri Lanka, Samoa, and Ghana. At the time of writing, 96 countries were connected to the ePhyto Hub with 30 countries using the generic ePhyto national system. An additional 48 countries were testing connections with the Hub and 29 countries testing the generic ePhyto national system.

The impact is substantial.10, Although the generic ePhyto national system was designed for countries with limited technical and financial capacity, some high-income countries have seen its benefit and are also using the generic system. The central hub decreased the need for bilateral trade agreements for the exchange of phytosanitary certificates, greatly reducing time, costs, and fraud.10 Traders report lower costs and fewer delays, with fewer shipments held up due to documentary non-compliance. The IPPC Strategic Framework 2020-2030 includes eight development agenda items to achieve its objectives, one of which is the harmonization of electronic data exchange by digitizing the production and exchange of phytosanitary certificates through the IPPC ePhyto Solution.12

“The IPPC Secretariat joined forces with various institutions and countries to take a leading role on electronic certification so trade of plants and plant products is safer, faster and cheaper. We could get this outstanding result in implementing ePhyto Solution thanks to the trust and support of the STDF.” 13

Implications for scaling: The global adoption of the ePhyto Solution – and future plans including development of a collaborative ePhyto initiative for Africa – suggests both horizontal and vertical scaling. It is now being adapted and expanded to pilot the use of e-veterinary certification in Latin America and the Caribbean through an ongoing STDF project led by IICA with partners.14

P-IMA

Developed through STDF’s Knowledge Work, and piloted and applied through STDF supported projects and project preparation grants, the P-IMA (Prioritizing SPS Investments for Market Access) framework is a structured, evidence-based tool that helps countries make informed decisions about where to invest limited resources in SPS capacity. Using a seven-step process grounded in multi-criteria decision analysis, P-IMA brings together public and private stakeholders to transparently identify and rank SPS investment options based on potential trade, socio-economic, and other impacts. Designed for adaptability across contexts, the framework does not assess SPS capacity itself but builds on existing data to guide strategic planning. The P-IMA approach has been replicated across regions and institutions, with applications ranging from national food safety authorities to regional economic communities. Its participatory design has proven adaptable to different governance and institutional contexts, facilitating uptake.

From 2015 to 2023, the STDF funded the application of P-IMA through one regional project grant and eight project preparation grants, with a total financial contribution of USD 591,379.15 By 2023, P-IMA had been applied 20 times, with nine of these instances being organizations applying the P-IMA of their own initiative (i.e. not through STDF support),15 sometimes with funding from other donors.

P-IMA’s core strength in scaling lies in its ability to promote ownership and alignment. It is an inclusive, evidence-based decision-making tool that fosters trust in the prioritization process and helps show the business case of respective investments linked to policy goals. Country stakeholders and international funders both view the prioritized SPS activities identified through P-IMA process as credible. Partially as a result, over half of the SPS capacity-building options identified through P-IMA were taken forward for funding into national action plans, legislation, or investment strategies, and over USD 2.8 million has been mobilized to support these investments. While the STDF sometimes funds some of the prioritized SPS investment options, interviewed participants reported that P-IMA results are regularly taken to other funders who view the application of P-IMA as credible evidence that investing in prioritized SPS capacities will lead to beneficial outcomes.

“It gives a platform for the stakeholders to discuss,… so that they are part of the decision, there’s ownership and there’s rationalization [in the] … use of resources”

“The Philippines’ B-SAFE development project, under the USDA-FFPr program, is adapting the STDF’s Prioritizing SPS Investments for Market Access (P-IMA) framework to realize its objectives of improving SPS capacity to boost agricultural productivity and trade of agrifoods…. Our participation in the P-IMA practitioner group session enables us to learn best practices from countries such as Belize, Vietnam, and Mozambique that have employed the P-IMA framework successfully.” 16

Using the P-IMA process requires technical capacity (including an economist, as well as SPS experts and a facilitator) and the ability to use the P-IMA software. Despite training SPS officials on P-IMA through STDF projects and project preparation grants, the number of experts with the expertise to apply P-IMA remains very limited, reducing opportunities for application. Limited technical expertise, costs in applying P-IMA, and limited ownership of the tool itself have resulted in P-IMA not being re-applied as needs evolve.

Implications for scaling: The tool has been applied in many contexts, suggesting significant horizontal scaling. The outputs of the tool (i.e. the prioritized SPS capacity investment options) are frequently embedded into the national strategies, action plans, donor proposals, and legislation of host countries, suggesting vertical scaling. However, the lack of re-application of the P-IMA suggests that there is still opportunity to scale deeply within the countries where it has been used by supporting institutionalization.

Centre of Phytosanitary Excellence

The Regional Centre of Phytosanitary Excellence was launched through an STDF project grant from 2008 to 2010.17 The grant was for USD 714,375 (total project value including in-kind contribution was USD 801,735). Although the Centre of Phytosanitary Excellence was initially implemented by Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI) and FAO, it was jointly managed by the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Services (KEPHIS) and the University of Nairobi, each of which assigned two staff members to support the Centre. An advisory board was developed to represent national and international organizations. During the grant period, the Centre offered four short, in-service courses and three university courses. The Centre also developed a Pest Risk Analysis tool to facilitate the regional sharing of pest information.18

Since the close of the STDF grant, the Centre of Phytosanitary Excellence has continued to grow and evolve. It now functions as a public-private partnership hosted by KEPHIS. It hosted four academic Phytosanitary Conferences and publishes the African Phytosanitary Journal. The Centre provides 16 trainings lasting nine hours to 10 days and offers specialty consultancy services. These activities suggest that the Centre of Phytosanitary Excellence continues to influence and support the development and adoption of good phytosanitary practices across the region. However, compelling quantitative or qualitative information on how the Centre has led to real-world, regional improvements in safe trade is unclear.

During the transition at the close of the STDF grant, the Centre of Phytosanitary Excellence engaged in a strategic evolution to be sustainable. Because KEPHIS had the institutional capacity, it became the host of the Centre, reducing ownership of other organizations originally involved in its governance, leading to decreased engagement and scaling opportunities. Another challenge was that the assumption that a training centre could successfully charge fees and become self-sustaining proved to be, at least partially, incorrect and COPE struggled with funding. Challenges running the training centre prompted the Centre to expand into hosting academic conferences and journal publication as alternate, funded activities. There is demand in these areas, and the Centre is continuing to influence the field through this work. KEPHIS’s responsiveness to the changes in demand and ability to keep the Centre functioning for the last 15 years demonstrate ingenuity in light of these challenges.

“In terms of scale up, you know…. It was not factored into the project. It was assumed that it would happen anyway because … there was demand for such a capacity building project “

Implications for scaling: The trajectory of the Centre of Phytosanitary Excellence highlights the critical role of planning for handoff and scaling, raising issues around governance, sustainability, and mission alignment. Questions emerged about optimum governance and business models and mission drift. The Centre’s experience prompts reflection on whether it is scaling its impact on safe trade in the region or simply sustaining them. The proposed project preparation grant to evaluate the Centre of Phytosanitary Excellence may be able to respond to these questions.19 Such an evaluation could increase the Centre’s ability to advocate for funding and provide the STDF with valuable information on the sustainability and scaling of the Centre.

Mainstreaming scaling

Although the STDF recently added scaling to its new Strategy, it has not yet determined how to operationalize the focus on scaling or the effects this will have on its work. The STDF is using this case study as an opportunity to reflect on its current positioning within the field and future opportunities to inform their decision to mainstream scaling. Therefore, any analysis of how scaling has been mainstreamed within the STDF must examine how scaling has been addressed incidentally, indirectly, and implicitly rather than through deliberate strategy. This does not reflect a gap in programming quality, but a conscious prioritization of other areas – groups are entitled to set their own priorities and scaling has not been STDF’s historically. While the STDF has not been systematically supporting scaling, it has been de facto supporting scaling through these other priorities and mechanisms of change.

“I don’t think there’s been deliberate attempts to do scaling. Perhaps, maybe, it’s in different forms”

Despite the new Strategy, there remain mixed views within the STDF Working Group and Secretariat regarding to what extent and how scaling should be mainstreamed. Interview participants generally fell into three categories:

- A large group of participants thought that the STDF already was supporting scaling and welcomed the opportunity to mainstream this through integration into the strategy, MEL, culture, incentives, etc. They thought that the formal operationalization of the STDF’s de facto scaling goal could increase the STDF’s effectiveness at catalysing change.

- Another large group of participants agreed that the STDF already was supporting scaling, but cautioned against formalizing the STDF’s approach to scaling. They thought the organic nature of the STDF’s current approach to scaling was a key to its success; formalizing it could make it too rigid, increase resource requirements, and distract from the mission.

“If the project is really interesting, it would sell itself, so it would be scalable anyways.”

- A small number of participants thought that the STDF’s role was not to support scaling. These people generally thought that the STDF should implement projects that directly support SPS capacity development and keep its scope limited.

We organize our discussion of the STDF’s approach to scaling around 12 enabling and operational elements that can be used to track Mainstreaming Scaling:6

- Vision, goals, and strategy

- Definition of and a common language for scaling

- Culture, incentives, and measures of success

- Partnerships and intermediary function

- Instruments, policies, and processes

- Dedicated resources

- Dedicated financial resources for scaling

- Internal resources for costs to operationalizing scaling

- Analytical frameworks, tools, and knowledge

- Integration into monitoring, evaluation, and learning

- Leadership

- Decentralization and localization

- Optimal scale; equity and inclusion

- Mechanisms for tracking mainstreaming goals

Vision, goals, and strategy

| HOW DO VISION, GOALS, AND STRATEGY RELATE TO SCALING?

Vision, goals, and strategy shape how it defines success—and whether scaling is treated as a priority or an incidental outcome. When scaling is embedded at the strategic level, it guides how programs are designed, how partnerships are pursued, and how success is measured. |

Fundamentally, the STDF’s vision, goal, and strategy align with scaling, making it a de facto scaling organization, even if it has not historically used this terminology. The previous strategy positioned the STDF as a catalyst for change and replication. The STDF did not position itself as a delivery mechanism for large-scale implementation. Instead, it defined its role as convening, innovating, learning, and catalysing safe trade practices that others—donors, governments, and international organizations—can adopt, adapt, and expand. This approach reflects the STDF’s limited funding and strategic focus on influence over execution, with an emphasis on embedding successful innovations into national systems and regional frameworks. Although the STDF provides some funding, it focused on “catalytic SPS improvements at national, regional, and global levels, driven by STDF partnership” (STDF Outcome 2). The STDF also supported “increased uptake of SPS good practices and knowledge products at the national, regional, and global levels” (STDF Outcome 1). Though scaling terminology was not used in these outcomes, the STDF’s emphasis on influence, uptake, and enabling environments reflects a clear logic of scaling by design. The intention of the STDF was to pilot innovative solutions that, if proven successful, could be replicated and scaled by others, not the STDF itself.

“What you can do from [US]$1 million, which is the largest amount you can get from a PG [project grant], is a pilot. It’s not transforming anything”

As of 2025, the STDF’s goal is “increased and sustained SPS capacity of public and private sector stakeholders in developing countries” with a vision of contributing to “sustainable economic growth, poverty reduction, food security, and resilience to climate change.” 2 This reflects a clear orientation toward vertical scaling—the transformation of national systems and institutional practices to address large-scale, global challenges. The STDF’s 2025-2030 Strategy mentions scale and scaling 31 times.3, Descriptions of both the Knowledge Work and Grant Mechanism highlight the importance of scaling innovations and successful models. Scale is also repeatedly mentioned in the description of the mechanisms of change that the STDF intends to leverage. It intends to:

- “Create an ecosystem that catalyses value creation, innovation, joint action and scaling, including through South-South dialogue and cooperation.”

- “Test and develop concepts for scalable innovations that improve SPS compliance and reduce interceptions for greater market access, and cut trade costs for both the public and private sector, and that can be rolled out more widely.”

- “Make the business case for scalable SPS innovations.”

- “STDF catalyses change and helps to scale SPS improvements in developing countries worldwide. STDF workstreams identify and disseminate scalable SPS innovations to policymakers and practitioners (including WTO SPS Committee delegates) and private sector stakeholders, and develop knowledge on how to scale SPS innovations at the level of the Working Group, Practitioner Groups and within projects and PPGs.”

- “Leverage increased financing to scale SPS capacity development (including investments from the private sector and other innovative financing sources).”

However, there are different views within the STDF about whether it pilots innovative solutions or aims to immediately improve outcomes. While not inherently at odds with one another, innovative solutions are often more expensive and higher risk than tried-and-true approaches in the short term. Implementing established approaches is often better at improving immediate outcomes while introducing new approaches tends to have greater opportunity for transformative change.

Summary and implications

Current actions to support scaling: The STDF’s vision, goal, and strategy are aligned with scaling goals, particularly vertical scaling.

Misconceptions and barriers to scaling: Although scaling is now in the STDF’s strategy, many STDF Working Group members still seem to be debating the merits of prioritizing scaling within the STDF. Some expect grants to generate knowledge that others can later scale, while others expect the STDF to directly deliver SPS outcomes. While many grants may be able to do both, strategic clarity on how the STDF will balance these two goals could improve alignment between funding decisions and STDF goals. Generating new knowledge often requires testing innovations that may not work, which results in a risk that projects will not directly deliver on SPS outcomes.

Incremental change opportunities: It may be helpful for the STDF to explicitly state where it intends to function on the transition to scale pathway (Figure 1). While everything functions on a continuum, clarity on the extent to which the STDF prioritizes piloting innovative solutions vs. achieving immediate SPS outcomes could support consistency in the strategy and action. Pilots could be positioned with the intention to catalyse widespread adoption of successful approaches. The four characteristics of projects likely to scale outlined in the section Scaling of STDF Projects could be used to identify promising pilots, which could be prioritized for funding. The STDF could also consider a formal recognition of the extent to which it aims to focus on horizontal scaling, vertical scaling, or scaling deep. This would allow it to consistently select activities that align with these objectives, again acknowledging that these are not strictly binary options. The STDF may wish to further specify the extent of its ambition and expectations from internal and external stakeholders with regards to scaling.

Transformational change opportunities: In addition to supporting pilots and developing new innovations, the STDF may wish to consider supporting the scaling of existing innovations and the transition to scale. This may position the STDF as an intermediary which mitigates the abandonment of promising innovations.

Definition of and a common language for scaling

| WHY IS A DEFINITION OF AND COMMON LANGUAGE FOR SCALING USEFUL?

The absence of an agreed upon understanding of scaling leads to fragmentation—staff, partners, and decision-makers may each interpret scaling differently, leading to inconsistent priorities and diluted efforts. Without a clear definition, scaling becomes difficult to integrate into strategic planning, program design, or performance assessment. Establishing a common language enables staff to recognize scaling opportunities, articulate realistic goals, and coordinate efforts across functions. It creates a baseline for tracking progress and assessing whether the group is contributing to lasting, widespread impact. |

There is no definition or common language for scaling within the STDF. Instead, as one participant noted, there is a “cloud of scaling.” Many interview participants, even some who did not support a formal focus on scaling, agreed that having a definition of scaling might facilitate communication, goalsetting, and strategic alignment. However, this view was not universal, with several people preferring that the topic remain “organic” and undefined.

The lack of a definition of and common language for scaling resulted in an impression that sustainability and spillovers are synonyms for scaling among many interview participants. The lack of a common understanding of the distinction between these terms has likely contributed to confusion about why the STDF should prioritize scaling when it already considers sustainability and spillovers.

“Scaling sustainability again to me, I really kind of use it as a synonym in a way.”

“I’m just going to call it sustainability, but I also mean scalability”

“The idea of the spillovers was probably with a view also to scaling up and other people adopting this type of thinking”

The ambiguous terminology around scaling has direct implications for the STDF’s core functions, such as the Working Groups grant approval processes. During the most recent review, many members mentioned that they supported applications because the projects were scalable. However, in the absence of a common understanding of what scalability means, these comments were difficult to interpret. While clearly of interest to the Working Group, scalability could not be used effectively by the group as a factor when deciding which projects to fund because there was not a consistent understanding of what a scalable project was.

Summary and implications

Current actions to support scaling: The STDF is already considering sustainability and spillovers, both of which are directly related to scaling. Scalability is discussed in the grant approval process.

Misconceptions and barriers to scaling: A lack of a common definition of scaling makes it hard for the STDF to communicate consistently and clearly about scaling. This is particularly apparent in divergent views about how to allocate the STDF’s limited grant funding, where clear terminology might help reach consensus.

Incremental change opportunities: The STDF could develop its own definition of scaling. A possible definition is provided in the section on Opportunities; however, this should be fully customized and owned by the STDF.

Culture, incentives, and measures of success

| CAN CULTURE, INCENTIVES, AND MEASURES OF SUCCESS AFFECT SCALING?

A culture that values and rewards efforts to enable uptake beyond project boundaries, paired with performance metrics tied to sustained impact rather than short-term outputs, makes scaling more likely to be pursued intentionally. When staff are incentivized to think beyond the immediate success of a grant, and when norms reinforce collaboration, knowledge sharing, and long-term influence, scaling becomes embedded in routine decision-making rather than treated as an optional add-on. These cultural and incentive structures create the internal alignment necessary for scaling to be acted on consistently, not just endorsed in principle (see Grand Challenges Canada as an example). |

STDF’s culture emphasizes collaborative support and trust-building. These values underpin its reputation as a credible and impartial convener, align with its role as a catalytic platform for SPS innovation, and could provide a strong foundation for scaling. Currently, however, norms within the STDF reinforce bounded responsibility around individual grants as opposed to shared responsibility for catalytic global change. Institutionally, scaling is considered outside the influence of the STDF by some interviewees, and something STDF and its staff cannot be accountable for. Some project managers do not consider it their responsibility to support the transition to scale, but the grantee’s job.

There is also limited performance monitoring related to scaling. While closeout reports are required, longer-term follow-up is informal, and uptake is not tracked. Without incentives or systems that prioritize long-term influence, project teams focus on delivering within the grant period. This reflects a view of success shaped by bounded project cycles, not systemic change.

Many interview participants advocated against prioritizing scaling because they thought this would create an expectation that everything must scale. There was a widespread view that, if everything cannot scale, the STDF should not focus on scaling at all. It is true that not every project is meant to scale, and many deliver valuable impact within their limited scopes. However, this does not mean that scaling cannot be prioritized as a general principle. It may be inappropriate, impractical, or unlikely for certain interventions to scale, and discrete projects filling specific gaps have their place. The STDF will need to decide the extent to prioritize scaling without undermining STDF’s capacity building mandate or distorting the balance of its portfolio.

“To confirm or guarantee that our projects are scalable, I think that’s a mistake because there’s so much stuff out there that it’s completely out of anyone’s control that it’s a formula to lose.”

Summary and implications

Current actions to support scaling: A culture that emphasizes collaborative support and trust-building is likely to lay a strong foundation for partnership-based scaling.

Misconceptions and barriers to scaling: Scaling is often considered outside the control of the STDF. While the STDF does not have complete control over what gets scaled, it can use its influence to exert some control over which projects are scaled. In addition, there is an impression that deciding to prioritize scaling would mean that everything must scale. However, these arguments do not necessarily mean that scaling should not be prioritized at all, only that it should be rationally prioritized.

Incremental change opportunities: The STDF could specify what types of grants and activities should be designed for scale and clearly articulate reasons to pursue activities that are unlikely to scale. The STDF could set specific targets for the percent of its portfolio with “scaling potential” or include scalability as one dimension among many it considers in deciding which activities to pursue.

Transformational change opportunities: The STDF could then set realistic targets for the percent of project grants and Knowledge Work outputs that should be designed to scale and the percent that should ultimately scale (see section on Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning).

Partnership and intermediary function

| WHAT IS THE PARTNERSHIP AND INTERMEDIARY FUNCTION?

In scaling theory, an intermediary is an entity that bridges the gap between innovation and large-scale adoption, facilitating connections between innovators, implementers, funders, and national systems. It builds capacity, aligns stakeholders, provides technical support, and supports adaptive management. The partnership function, meanwhile, refers to the role of convening, networking, and leveraging relationships to channel resources and ensure sustainable uptake. Both can facilitate engagements between grantees and donors to secure funding for scaling.

|

With limited resources and a mandate to catalyse, not implement, change the STDF’s most powerful lever for scaling is its role as an intermediary. Rather than scaling solutions directly, the STDF aims to create the conditions for others to do so: convening partners, brokering relationships, and amplifying what works. Although it has not explicitly adopted a scaling lens, the STDF’s Global Platform functions as a passive intermediary; it creates the enabling conditions for networking and partnership that could facilitate scaling, but does not actively support activity design and handoff for scale.

The STDF’s credibility as a neutral, honest broker is seen by internal stakeholders and external evaluators5 as a core enabler of this catalytic role. Its ability to convene diverse actors and align interests through the Global Platform has repeatedly opened doors for the uptake and adaptation of STDF-supported innovations. In practice, these engagements often take the form of sideline conversations, informal introductions, or participation in project closeout events. Interview participants cited several specific examples of concepts and approaches that the STDF championed, and their organizations adopted. However, these efforts are currently heavily dependent on individual initiative rather than institutional process.

“We emulated because… there was so much to be learned from it. And so that was a sort of organic scaling-up where we just sort of parasitized … what they were doing because it was good”

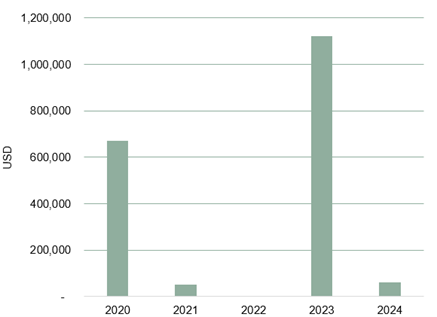

The design of STDF’s Grant Mechanism already supports its catalytic and intermediary function. Project preparation grants are often used to develop high-quality proposals to attract funding from other donors. Project grants are structured to promote broad ownership and support, requiring applicants to engage relevant ministries, secure endorsements from regional bodies, establish multi-stakeholder steering committees, and contribute in-kind or financial support. However, leverage of external funding is inconsistent and highly variable (Figure 2).

Figure 2: External funding leveraged

|

Project managers note that facilitation of introductions to support transition to scale requires significant time-resources and that securing follow-on funding tends to be slow and uncertain. Handoffs depend on precise alignment between the innovation and the strategic priorities of potential funders, something that is difficult to engineer without dedicated resources and strategy. The STDF’s high reliance on international implementing partners allows it to leverage the networks of these implementing partners rather than needing to conduct all intermediary and relationship building work itself. However, this may reduce opportunities for local partners. Grantees, for their part, question how they can pursue scale or follow-up activities without transition support (see section on Dedicated Resources for Scaling).

“Sometimes we [grantees] have projects where the project ends and we wash our hands and that’s the end of the story. I think partnerships also ensure that that doesn’t happen.”

The STDF Working Group has the potential to support handoff and project scaling and has done so in several cases. Its composition—bringing together donors, international organizations, and regional bodies—positions it well to function as an intermediary; however, its engagement with projects is generally limited to proposal review and selected updates. Individual members sometimes independently support the continuation or expansion of STDF-funded work, but there is no formal process linking Working Group members with projects that align to their organizations’ interests to facilitate handoffs. Many of the Working Group members represent extraordinarily large organizations, and sometimes parts of their organizations seem to scale (or be interested in scaling) STDF projects independently of the Working Group members. As a result, the potential of the Working Group to function as an intermediary platform has remained unrealized in practice.

The gaps identified in coordination, follow-up, and systematic handoff should not be seen as failures, but as natural outcomes of an approach that has prioritized other objectives. These are not signs of underperformance, but indicators of untapped potential. If STDF were to adopt scaling as a strategic focus, the existing structures of the Grant Mechanism, Working Group, and Global Platform offer a strong base and clear opportunities for deeper and more intentional partnership and intermediary work to support scaling.

| SCALING THROUGH INTERMEDIATION AND PARTNERSHIP20, 21, 22

A project example: An STDF project developed a locally adapted Code of Practice for the peppercorn value chain in Viet Nam, Lao PDR, and Cambodia. The project was generally successful and improved the safety of the peppercorn supply chain in all three countries. Representatives from GIZ and the EU Delegation in Cambodia were invited to the project closeout meeting and they committed to scaling the Code of Practice into the Euro 10 million EU-German CAPSAFE project focused on sustainable farming practices and market opportunities for smallholder farmers in two value chains (including peppercorn) in Cambodia. This is expected to increase the reach of the guidelines and the adoption of best practices developed by the STDF project. Quotes from Annual Reports: “The STDF’s work is contributing fully to the new FAO strategy to support the transformation to more efficient, inclusive, resilient and sustainable agri-food systems.” Maria Helena Semedo, Deputy Director-General, FAO, 2021 Annual Report “The STDF, through PPGs [project preparation grants] and knowledge products, serves as an incubator for innovative ideas that we can use to strengthen, scale and apply in our programmes.” Betsy Baysinger, Division Director, Foreign Agriculture Service, USDA, 2023 Annual Report |

Summary and implication

Current actions to support scaling: The STDF’s partnership work, particularly its Global Platform, create the space for networking and intermediation, which supports vertical scaling and handoff.

Misconceptions and barriers to scaling: While the STDF creates the space for grantees to engage with funders, the STDF Secretariat and Working Group do not always actively use their influence to facilitate handoff. Grantees and implementers are often expected to proactively seek follow-up opportunities. There is an assumption among some in the STDF that successful projects will scale themselves, without needing intermediation and the active support of stakeholders. In our experience, this is often impractical and results in promising innovations being abandoned.

Incremental change opportunities: The STDF may wish to develop a flexible framework specifying the intermediary functions it would like to pursue, allowing for different approaches depending on grant contexts. It could specify that implementing partners are expected to have their own networks to facilitate the transition to scale or that grantees should include funding for networking in their application budgets.