Abstract

Development funders have an important role to play in supporting the pursuit of sustainable impact by the implementers of development programs, but this requires that they systematically integrate the objective of scaling, i.e., achieving sustainable impact at scale into their mission and their operational practices. Evaluation and evaluation guidelines are potentially important instruments for mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations. This paper provides an indicative framework for how evaluation guidelines could address scaling. It then reviews the OECD-DAC EvalNet evaluation guidelines, the OECD-DAC Peer Review methodology and the MOPAN assessment methodology, as well as publicly available evaluation guidelines for 18 large bilateral and multilateral official funder agencies, to determine to what extent and how they incorporate an explicit focus on scaling.

For the OECD-DAC and MOPAN guidelines the paper finds that, while scaling is not entirely absent, the guidelines do not treat scaling effectively, let alone provide helpful guidance to evaluators on how to assess their agency’s approach to scaling and how to evaluate their performance on scaling for specific projects or programs or overall. Since many of the evaluation guidelines of the individual funder agencies are based on the OECD-DAC EvalNet guidelines, this represents a missed opportunity to influence and support the evaluation units of official funder organizations and, indirectly, to strengthen the incentives for funder agencies to mainstream scaling,

The paper finds that for ten funder agencies evaluation policies or guidelines do not address scaling; for another four, there is some, but only very limited coverage; while for a final four agencies scaling is a central part of the evaluation policies or guidelines, with varying degrees of guidance provided. This last set of cases demonstrates that the inclusion of scaling in evaluation guidelines is possible without a fundamental departure from existing evaluation approaches.

The paper then reviews 17 evaluations and assessments for four agencies: four OECD-DAC peer reviews, three MOPAN assessments, six IFAD program and project evaluations and four World Bank country program and project assessments. As would be expected, the IFAD evaluations have the most extensive consideration of scaling, while World Bank and OECD-DAC peer reviews pay very little, if any, attention to scaling. MOPAN assessments somewhat surprisingly do consider scaling to some extent, even though the MOPAN methodology provides little guidance on scaling to assessment teams.

The paper concludes with a summary of findings and recommendations for how scaling could be more systematically and effectively addressed in evaluations.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE

Introduction

The Scaling Community of Practice is undertaking an “action research” initiative on the mainstreaming of scaling in development funder organizations. The initiative aims to collect information and lessons on how funder organizations have or have not supported scaling of development innovations and interventions, and to promote more effective and systematic mainstreaming of scaling in funder organizations. The initiative comprises various components, including most prominently a compilation of case studies on how selected international development funders have mainstreamed scaling into their funding approaches. Another important component of the initiative reviews the evaluation guidelines and practices of selected official development funders to determine to what extent and how they include scaling considerations. This paper reports on the findings of this review.

The underlying presumption for this work is that (a) a more systematic focus on scaling by funders is necessary to achieve development goals; (b) this focus will only occur if and when there are institutional and individual incentives for scaling within development finance institutions; (c) evaluations can be an incentive and learning opportunity for funder organizations to improve their development effectiveness and in particular their focus on supporting sustainable impact at scale; and (d) including scaling in evaluations would also allow for learning as to how to better mainstream scaling in funder organizations and how to effectively support scaling with development finance.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 sets the stage by explaining why evaluations of scaling matter and how to address scaling in evaluations. Section 3 reviews the evaluation guidelines and methodologies developed by the OECD-DAC Network on Development Evaluation (EvalNet), by the OECD-DAC Peer Review unit, and by the Multilateral Organizations Performance Assessment Network (MOPAN) in terms of their consideration of scaling. Section 4 assesses the evaluation guidelines of 18 official international development funding organizations from a scaling perspective. Section 5 reports on how scaling was reflected in 17 specific evaluations and assessments of four official development agencies. Section 6 concludes with a summary of findings and recommendations. Annex contain references to and excerpts from evaluation documents.

Setting the stage: Why evaluations of scaling matter and how to consider scaling in evaluations

This section addresses a number of questions to help clarify the coverage and rationale of this paper and offers an approach to how scaling could be considered in evaluations.

What types of evaluations are covered in this paper?

There are broadly two types of evaluations:

- Impact evaluations that assess the impact of specific innovations or interventions, often applying some form of the randomized control trial (RCT) method; these are most frequently carried out by specialized research institutions (such as J-PAL or 3ie) and increasingly commissioned by funder organizations in connection with the projects they finance; the principal purpose of these evaluations is to learn what is the impact of an innovation or intervention.

- Project and program evaluations of official multilateral and bilateral funders, often carried out by independent evaluation units reporting to the governing boards; these evaluations are generally conducted after project completion, but in some cases also as interim evaluations during project implementation or as evaluations of overall sectoral or organizational programs; they serve the dual purpose of accountability and learning; and they generally employ a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods, increasingly also drawing on the results of RCTs.

This paper focuses on assessing the extent to which scaling is considered in the latter of these two types of evaluations for selected larger multilateral and bilateral funder organizations and refers to them as “evaluations.”

Why focus on evaluations?

As noted, evaluations serve the dual purpose of accountability and learning. As such, they have both incentive and learning effects. Incentive effects can result from the fact that evaluations are used by governing bodies to track the effectiveness of the financing of their organizations and to assess and guide management in the execution of their tasks. In addition, evaluations can contribute to the understanding of funder staff and management and of recipient organizations in the design and implementation of projects and programs. The extent to which evaluations serve the incentive versus the learning function depends on many factors, including the quality and timeliness of the evaluations and the extent to which they are taken seriously by the governing bodies and the managements. It is also well known that there is a tension between the accountability and learning functions of evaluations, since a focus on the former may impede the latter, as management tends to focus on defending its track record against any perceived criticism, rather than focusing on the lessons that can be learned from evaluations.

This paper is based on the presumption that evaluations are one of the tools for mainstreaming scaling into funder organizations: if evaluations include scaling as one of the key aspects of development effectiveness, they will have both incentive and knowledge effects on the funder organizations and support a more proactive focus on scaling. By contrast, an absence of a focus on scaling in evaluations signals to the organization and its managers and staff that scaling is not a relevant consideration for them.

It could be argued that since standard evaluation policy demands that evaluators evaluate projects against the objectives set at the time of project design, evaluators cannot consider scaling if the funder’s operational mandate and policies do not require a focus on scalability and scaling in project design and implementation. However, if development effectiveness requires a pursuit of sustainable impact at scale, as it surely does, then evaluations – and evaluation guidelines – should investigate whether or not funder-supported programs and projects effectively support a longer-term scaling strategy. Moreover, to the extent that development finance institutions increasingly include scaling among their organizational objectives, evaluation methodology needs to take account of this.

Why focus on scaling?

Scaling can be defined as follows: “A systematic process leading to sustainable impact affecting a large and increasing proportion of the relevant need.” In this paper we include under the term of “scaling” the analysis of scalability (i.e., whether and under what conditions scaling is advisable and possible), the actual scaling process or pathway from idea and pilot – or from one project to subsequent ones – to impact at scale, and ultimately to sustainable operation at scale.

Scaling has in the past not featured as one of the main criteria for evaluations. A group of World Bank experts in 2020 carried out a review of common evaluation approaches and methods for an audience of independent evaluation office staff of official funder organizations. Not once does that review touch on scaling or replication as a topic of actual or potential concern for evaluation. And, as our present paper demonstrates, the evaluation guidelines of many official funders still do not include an explicit focus on scaling, let alone guidance on how to assess scaling. So why worry about scaling?

Over the last fifteen years, the scaling agenda has gained prominence as a tool to achieve sustainable development (and, more recently, climate) impact at scale in recognition of the fact that a predominant focus on funding innovation and the prevalent practice of funding one-off projects (“pilots to nowhere”) will not achieve ambitious development (and climate) goals. Instead, funders should support scaling pathways in which innovation and individual projects play an important role, but where the critical challenge is to identify a longer-term vision of desired impact at scale, and to assess (a) which intervention is best suited to achieve the long-term goal, (b) who the principal actors are that will promote the scaling process, and (c) what the enabling conditions are that have to be put in place to assure that sustainable scaling happens. Including scaling as a key consideration in funder support for development programs and projects is now increasingly recognized as a priority and therefore it should also be an important consideration for evaluations.

Why look at evaluation guidelines?

Evaluation guidelines (and methodologies), as their name indicates, are designed to guide the evaluators in the execution of the evaluations of specific projects and programs. An absence of scaling criteria and guidance in evaluation guidelines in practice means that more often than not evaluators will not consider the scaling dimension in their evaluations. Even where evaluation guidelines refer to scaling, a lack of more detailed guidance on what scaling means and how it can be assessed will likely mean that the evaluation of scaling aspects will be at best superficial and likely not be as sound and helpful as could be the case. Therefore, evaluation guidelines should not only include a reference to scaling as a criterion, but also provide guidance on how the criterion is to be applied.

What should evaluation guidance on scaling look like?

At a minimum, scaling should be an explicit criterion in evaluation guidelines together with a clear definition of scaling. It could be combined with a sustainability criterion, since – as the above definition of scaling indicates – impact at scale has to be sustainable to be of lasting value.

In the recent work on mainstreaming scaling by funder organization, an important distinction is drawn between “transactional” and “transformational” scaling. Transactional scaling focuses on “more” – more money, more one-off effort and impact, replication of interventions with no or only limited concern about sustainability and the need for adaptation to ecosystem conditions). Transformational scaling focuses on the pursuit of longer-term scaling pathways beyond project end and on the creation of the enabling systemic conditions for sustained and scalable outcomes, adapted to local conditions. Evaluation guidelines should reflect criteria that focus on transformational scaling, not only transactional scaling.

However, a mere inclusion of scaling among the evaluation criteria will not suffice, as noted above. Additional guidance to evaluators will be needed. A fully articulated evaluation guidance for scaling will depend on the organization for which it is designed. Here only some key elements are highlighted in Box 1 in the form of questions that evaluators should address. A more detailed set of guidelines could build on the “Scaling Principles and Lessons” of the Scaling Community of Practice, adapted as may be appropriate to the specific characteristics of a given funder organization.

Box 1. High-level evaluation guidance questionsDo program or project design and implementation

|

Which types of funder organizations are included in this review?

This review of evaluation guidelines covers only selected large official multilateral and bilateral development agencies for which the most recent evaluation guideline (or policy) documents could be readily accessed. In addition, as noted in the introduction, the evaluation guidelines developed by DAC EvalNet, by the OECD-DAC Peer Review unit, and by MOPAN were reviewed and are summarized and assessed below.

What is not covered in this review?

The paper does not consider how impact evaluations (and especially RCTs) have been and can be used to support scaling; and the paper does not deal with monitoring practices during project or program implementation. Furthermore, the review of how specific evaluations of selected funders and their projects have addressed the scaling dimension is at best indicative given the limited number of evaluations and assessments that we reviewed. A more comprehensive review of project and program evaluations will be required to reach definite conclusions on current evaluation practices.

Assessment of evaluation guidelines and methodologies by OECD-DAC and MOPAN

In this section, we review the evaluation guidelines and methodologies of OECD-DAC and MOPAN by checking whether the concepts of scaling, scalability, impact at scale, replicability and replication appear in the text, either among the evaluation criteria or as subsidiary considerations. We start with the DAC EvalNet guidelines, due to their overarching importance in shaping the guidelines of many individual evaluation agencies. We then consider the DAC peer review guidelines and the MOPAN assessment methodology.

DAC EvalNet Guidelines

According to a recent expert analysis of the DAC’s history and role, “the DAC EvalNet is the nearest body there is to be the international reference point in [the evaluation] field… The normative work by the network – evaluation quality standards, principles, evaluation criteria – has had a very strong impact on evaluation policies and systems and on the conduct of evaluation, also beyond DAC members. The criteria are used to inform the questions to be addressed in evaluations of development programmes and projects by NGOs, developing countries, DAC members and multilateral agencies and banks.”

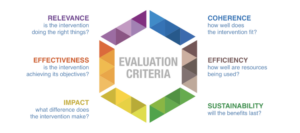

EvalNet identifies six criteria in its most recent (2021) evaluation guidelines, as shown in Figure 1. In none of these six criteria, their definition and their summary explanations does the scaling concept appear. However, scaling does feature in a subsidiary, optional or indirect role in the explanation of “Impact” and “Sustainability” criteria.

Figure 1: OECD-DAC EvalNet evaluation guidelines

Source https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/daccriteriaforevaluatingdevelopmentassistance.htm |

For the “Impact” criterion, the question “Is the intervention leading to other changes, including ‘scalable’ or ‘replicable’ results?” is included among a list of other questions that the criterion “might cover” (p. 65). However, there is no indication that this is a core issue to be addressed and no guidance is given on what the terms ‘scalable’ and ‘replicable’ imply or how they should be assessed. The definition of the impact criterion also refers to “potentially transformative effects of the intervention” and asks the question “Is the intervention transformative – does it create enduring changes in norms – including gender norms – and systems, whether intended or not?” (p. 65) This focus on transformative effects is welcome as it addresses the transformational aspect of scaling that we stressed in Section 2 above, but again there is no guidance on how evaluators should assess the transformational aspects of scaling in a project. Finally, under the heading of “unintended side effects” there is also a reference to “whether there is scope for innovation or scaling or replication of the [unintended] positive impact on other interventions.” (p. 65)

For the “Sustainability” criterion, the text notes that: “The lessons [from sustainability analysis] may highlight potential scalability of the sustainability measures of the intervention within the current context or the potential replicability in other contexts.” (p. 72) While this statement does not actually require evaluators to consider scalability or provide guidance on scalability analysis, it does imply correctly that sustainability and scalability analysis are closely related, since sustainability analysis “[i]ncludes an examination of the financial, economic, social, environmental and institutional capacities of the systems needed to sustain net benefits over time.” (p. 71) These are precisely the enabling conditions that need to be analyzed for transformational scalability analysis, albeit from a scaling perspective, not merely from a sustainability perspective. For example, the existing financing arrangements at the end of a project might allow sustaining its impact over time, but might not be sufficient or appropriately configured to allow scaling.

Under the sustainability discussion, there is also a reference to exit planning. “Evaluations should assess whether an appropriate exit strategy has been developed and applied, which would ensure the continuation of positive effects including, but not limited to, financial and capacity considerations. If the evaluation is taking place ex post, the evaluator can also examine whether the planned exit strategy was properly implemented to ensure the continuation of positive effects as intended, whilst allowing for changes in contextual conditions as in the examples below.” (p. 72) This is an important consideration for an evaluation of scaling also, but again, the specific requirements for effective exit planning for sustainability may differ from those for scaling. Moreover, exit planning, while helpful, is not enough as a device to support scaling. As the scaling literature stresses, scaling has to be considered from the beginning of a project or program and planning for what happens at and beyond the end of a project has to be part of the design and implementation of the project and not relegated to the preparation of an exit strategy towards the end of a project.

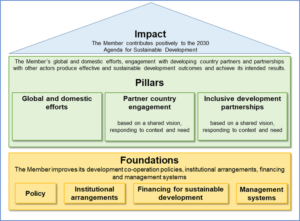

DAC Peer Review Guidelines

The DAC Peer Review is set up by mutual agreement of DAC members (i.e., bilateral official funders). “Through a combination of accountability and learning, DAC peer reviews seek to promote individual and collective behaviour change of DAC members in order to achieve improvement in their development co-operation policies, systems, financing and practices.” The intermittent peer reviews follow a methodology developed and agreed by DAC members and are supported by an organizational unit in the OECD-DAC Secretariat. The methodology builds on four “foundations” and three “pillars.” (Figure 2 on the next page)

Figure 2: The DAC Peer Review methodology

Source: https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC(2020)69/FINAL/En/pdf |

The DAC Peer Review guidelines have only one passing reference to scaling in the context of the Management Systems foundation under the heading of “Adaptation and innovation”, where this statement can be found: “The member has capabilities to introduce, incentivise and enable, measure the impact of, and potentially scale, innovation in its policies and programmes.” (underlining added) However, no guidance is provided to peer reviewers on how they might assess an organization’s ability to “potentially scale innovation”. There is no reference to how a bilateral funder’s operational policies and procedures of project and program finance support or hinder sustainable scaling, no consideration whether individual interventions are effectively linked to longer-term development objectives, such as the SDGs, and no comment on whether monitoring and evaluation include considerations of scaling. There are references to important components of a scaling approach, including partnerships (p. 17/18), stakeholder participation (p. 21) and financial leverage (p. 22), but these references are not explicitly linked to scaling.

MOPAN Assessments

MOPAN is a network of 21 member countries – among them the major funders of the multilateral development finance institutions – aiming “to improve the performance of the multilateral system, making it stronger, better and smarter.” The MOPAN Secretariat manages regular assessments of individual multilateral development finance organizations. These assessments “provide a snapshot of an organisation’s performance by taking into account the organisation’s history, mission, context, trajectory and journey. Assessments cover four areas of organisational effectiveness: strategic management, operational management, relationship management and performance management, and results.” The assessments serve not only a learning function, but also an accountability function, since MOPAN members use the results inter alia to help them determine the financial contributions they make to the multilateral organizations. The assessments are guided by a methodology which is regularly updated. The most recent one (MOPAN 3.1) was issued in 2020. A revision of this methodology is under preparation at the time of the writing of this paper.

The MOPAN 3.1 methodology makes no reference to scaling in the main text or in the Annex dealing with key performance indicators (KPI) and score descriptors. As with the DAC peer review, there are elements in the methodology that are potentially relevant for an assessment of the organization’s approach to scaling, including capacity analysis (p. 63), sustainability and its enabling factors (p. 64), partnerships (p. 65), and results-based management (p. 67). But, again as for the DAC peer review, there is no link between these elements and a systematic focus on scaling in the assessment methodology.

Summary assessment

In sum, while scaling is not absent from the DAC EvalNet evaluation guidelines, evaluation of scalability and scaling is treated as optional, with no requirement for a systematic, in-depth evaluation of scalability and scaling. To the extent the concepts of scalability, scaling and replication are referenced, there is no definition nor guidance on how to apply these concepts. The references to transformative impact and to the enabling factors for sustainability provide a potential entry point for further exploration of the scaling aspects in evaluation, but the EvalNet guidelines do not go beyond offering mere hints to that effect.

The DAC Peer Review and the MOPAN assessment methodologies, like the EvalNet guidelines, have very little consideration of scaling. While some elements of the methodologies are relevant for an evaluation with a scaling focus, that focus is currently lacking. In essence both official agency development review functions do not provide any relevant guidance on whether and how the multilateral and bilateral funders can support scaling through the programs and projects that they fund.

Looking ahead, the OECD-DAC Secretariat is currently preparing a scaling guidance document. It can and should serve as a basis for the preparation of guidance documents by EvalNet, DAC Peer Review and MOPAN evaluators on how to assess the scaling aspects of organizations, programs and projects that they are tasked to evaluate.

Assessment of evaluation policies, standards and guidelines of individual official funders

We searched the websites of the evaluation offices of 18 official bilateral and multilateral funder organizations listed in Table 1 for statements on evaluation policies, standards and guidelines. We reviewed those we found for any explicit consideration of scaling, impact at scale, scalability, replication and replicability. We summarize in this section our findings for the 18 organizations grouped by the extent to which scaling is a focus of their evaluation approaches.

Table 1: Funder organizations grouped by the extent of focus on scaling in evaluation guidance documents

| No mention of scaling | Some/limited mention of scaling | More extensive treatment of scaling |

| Bilateral | ||

| AFD | GIZ | |

| GIDE | USAID | |

| JICA | ||

| KfW | ||

| UK (FCDO/DFID) | ||

| Multilateral | ||

| AfDB | ADB | GCF |

| EBRD | World Bank Group | GEF |

| EIB | IFAD | |

| IADB | UNDP | |

| UNEG | ||

Funder agencies for which scaling is entirely absent in evaluation policy or guidance documents

For ten agencies – five bilateral and five multilateral – we found no mention of scaling in the documents that we reviewed. Most of the documents are labeled “evaluation policy” documents and focus predominantly on organizational process and responsibilities, rather than on evaluation criteria. Or they deal with “norms and standards” (as in the case of the UN Evaluation Group, UNEG). Three of the agencies refer to the DAC evaluation criteria (AFD, EBRD and KfW) without any mention of scaling. It is possible that each of the agencies listed in the first column have internal evaluation guidance documents that spell out evaluation criteria and approaches in greater detail, but these were not to be found in the publicly available online documentation.

Funder agencies for which there is some mention of scaling in evaluation policy or guidance documents

We found four funder agencies whose evaluation policy and guidance documents referred in passing to scaling: two bilaterals (GIZ, USAID) and two multilaterals (ADB and the World Bank Group). As detailed in Box A1 in Annex 3, the references relate to the need to consider scaling and replication, assess scalability and the conditions supporting it, and to the use of impact evaluation in informing the scaling option. However, none of these references include scaling as a key criterion for assessing development effectiveness. None define what scale or scaling is, nor do they refer to the need to consider how systematically and effectively scaling is pursued. They do not contain a serious consideration of what are the conditions for successful scaling, what a scalability analysis consists of, or how scaling is incorporated in project and program monitoring and evaluation. All the guidance documents refer to the OECD-DAC criteria.

Funder agencies for which scaling is treated more extensively in evaluation policy or guidance documents

The evaluation guidance documents for four of the 18 funder agencies treat scaling more extensively; all four are multilateral funders (GCF, GEF, IFAD and UNDP). The details for each funder are summarized in separate boxes in Annex 3 at the end of this paper. (Boxes A2-A5 in Annex 3)

The highlights are as follows:

- Scaling is a central feature in all four guidelines, and an explicit evaluation criterion in three (except UNDP); scaling is specifically performance rated in IFAD evaluations.

- Scaling is linked with paradigm shift (GCF), with catalytic impact (GEF), and with transformative change (IFAD).

- All link scaling closely with replication and sustainability.

- Evaluation guidelines for three of the four agencies provide definitions of scaling (except UNDP).

- GCF and IFAD focus on long-term scale goals (including the SDGs or climate goals) and scaling pathways towards them.

- IFAD and UNDP consider the need to explicitly plan for scaling beyond project end.

- GCF and IFAD note that enabling factors for scaling and local conditions need to be considered.

- GEF and UNDP note that innovation needs to aim for impact at scale.

The fact that four agencies have evaluation guidelines that treat scaling more extensively, if not all comprehensively, is a signal that scaling is becoming a focus in evaluation and that including it as an important criterion with some guidance for its application is indeed feasible and appropriate and not too burdensome for evaluators. At the same time, they demonstrate the need for guidance for consistent and comprehensive and effective assessment of scaling in evaluation, not only to ensure that other evaluation agencies mainstream scaling into their evaluation criteria and guidance, but also to achieve some consistency and comparability in evaluation of scaling across institutions, as is provided by the DAC EvalNet guidance for other criteria.

Review of scaling in selected evaluations by four major development finance organizations

As a final element of the assessment of how scaling is reflected in the evaluations of official funder agencies, we reviewed selected evaluations of four funder organizations: OECD-DAC peer reviews, MOPAN assessments, and evaluations of IFAD and the World Bank country program and project. In each case, we focused on whether the transformative scaling agenda was addressed and whether the peer reviews, assessments or evaluations did so in a systematic way, beyond mentioning scaling and replication in a pro forma manner.

Although we reviewed a total of 17 evaluations, the sample is small and can only give a broad impression of how scaling is treated in actual evaluations. The extent to which evaluation guidelines support or limit systematic consideration in evaluations can therefore only assessed in a preliminary manner.

OECD-DAC peer reviews

We reviewed four OECD-DAC peer reviews: Germany (2021), Switzerland (2019), the United Kingdom (2020) and the United States (2022).

As noted in Section 4, the OECD-DAC peer review guidelines only make a passing reference to scaling and provide no guidance on how scaling is to be assessed. Each of the four reviews contain sporadic references to scaling: 3 for Germany; 5 for Switzerland; 10 for the UK; and 4 for the US. Box A6 in Annex 3 presents relevant excerpts for each of these OECD-DAC reports.

The four reviews deal with scaling to a varying extent and focus on different aspects. The most extensive treatment of scaling is in the review for the UK, which notes that the UK has the capacity to achieve the desired breadth, depth and scale of impact at country level. It manages to leverage public and private resources, supports payments for results, and has had some success in bringing its innovation portfolio to scale. It also pursues impact at scale in its humanitarian and crisis response interventions. But the review also recommends “to formally build a continuum of support, ranging from early technical assistance to investment at scale.” (see Box A6).

The peer review of Switzerland gives its programs credit of being longer-term in focus, with effective partnering in the interest of impact of scale, esp. with multilateral organizations, and in pursuing impact at scale for the innovations that it supports, in particular through its global programs. However, “[e]ven though replicability and scale-up are part of the projects’ selection criteria, … replication remains a challenge.” (see Box A6)

For Germany, the peer review focuses mostly on scaling up of financing, effort and engagement by the German development finance agencies, rather than on impact. It notes that Germany pursues partnerships for greater scale and has an innovation program that also supports scaling of successful innovations. It also observes that Germany continues to have problems in moving from support for small, stand-alone projects to providing multi-year program funding for its CSO partners.

The peer review for the US provides encouragement for scaling up localization (i.e., intensifying effort to achieve localization) and recommends that the lessons from successful systemic change under programs supported by the Millennium Challenge Corporation be adopted by other agencies.

Despite these references to scale, the treatment of scaling in these four peer reviews remains sporadic, even for the case of the UK. No effort is made to assess whether and how scaling is systematically pursued by the countries’ development assistance programs and whether or not the enabling organizational factors are in place in the funder organizations to support an effective pursuit of the scaling agenda.

MOPAN assessments

We reviewed three MOPAN assessments: UNDP (2021), UNICEF (2021), and the Global Fund (2022).

As noted in Section 4, the current MOPAN peer review guidelines make no reference to scaling. However, all three MOPAN assessments include significant references to scaling: 10 references each for UNDP and UNICEF, and 13 references for the Global Fund. Box A7 in Annex 2 presents relevant excerpts about scaling for each of these MOPAN reports.

The fact that scaling is mentioned at all and that failure to support scaling sufficiently is mentioned as a critical element in all three reports, is encouraging in that it shows that MOPAN assessment teams are aware of the need for the funder agencies to focus on the scaling agenda. The reports highlight the need for effective exit management (UNDP assessment), pay significant attention to sustainability and partnerships (all three assessments; the UNICEF assessment refers even to the need for transformational partnerships), and note the importance of “cost-efficiency” and economies of scale (UNICEF assessment) – all important ingredients for successful scaling.

However, a number of significant limitations of the current approach are reflected in the three assessments:

- Most of the references to scaling are based on the independent evaluations carried out by the organizations themselves. This raises the question of whether MOPAN assessment teams on their own would have focused on the scaling aspect or not. More assessments will have to be reviewed to provide a definitive answer to this question.

- The reports cite examples of more or less successful scaling with the support of the three agencies, but in none of the reports is there a coherent, systematic assessment of the extent to which a focus on scaling has been mainstreamed into the funding practices of the organizations, in contrast to the treatment of, say, sustainability and partnerships.

- There is no assessment of the role of scale impact and scaling in the mission and goals of the organizations, nor whether scaling is an explicit factor in the funding policies and criteria, in project preparation and implementation modalities, in management and staff incentives, and in monitoring and evaluation. There is no consideration of whether or not scalability assessments are carried out by the agencies.

- To the extent the assessment reports critique the scaling performance of the three organizations there is generally no effort to explain the reasons for the shortfalls, nor recommendations what needs to be done to improve scaling performance.

IFAD evaluations

We reviewed six evaluations: one sub-regional evaluation for IFAD interventions in fragile states (2023), one project cluster evaluation for rural enterprise support (2023); three country program evaluations (Guinea-Bissau, Indonesia, Kyrgyz Republic; all 2023); and one evaluation of a rural market development project in Egypt (2023).

As noted in section 4 above, IFAD’s evaluation guidelines focus on transformative scaling, esp. through partners. However, there is considerable variation in the way the guidelines have been implemented across the six evaluations. Box A8 in Annex 2 presents relevant excerpts from these evaluations.

The most substantive in its focus on scaling – and indeed exemplary for how evaluations should address scaling – is the subregional evaluation in fragile states. It devotes three pages to considering the design, implementation and evaluation in IFAD projects in the Central-West Africa region from a scaling perspective. It concludes its assessment with these key points:

“Scaling-up results with governments have been very limited, with few good examples found in Nigeria and Niger. There is evidence of scalingup through other development partners, but IFAD’s monitoring systems rarely seem to pick these up. Supporting governments in defining and implementing strategy for scaling up is essential in the G5+1. Mixed scaling-up results achieved in the G5+1 contexts reflect weaknesses in terms of KM [Knowledge Management] and policy-engagement activities.” (p. 81)

This evaluation also has an explicit and substantive focus on sustainability.

The cluster evaluation of projects in support of rural enterprises falls into the opposite category: There is no separate discussion of scaling, only three scattered references to scaling (and another three to “scaled”). There is a discussion of the introduction and uptake of new technologies and practices and the factors limiting them; and of what is needed to support the creation and growth of rural enterprises. While these give a glimpse of scaling related issues, they do not represent a systematic evaluation of IFAD’s support for scaling rural enterprises.

All three Country Strategy and Program Evaluations (CSPEs) have a brief section (1/2 to 1 page long) dedicated to scaling, under the heading of “sustainability” or “sustainability and scaling,” usually with a more substantive focus on sustainability than on scaling. The evaluations tend to focus on selected examples of IFAD support for relatively successful scaling and note factors that have contributed to or impeded the scaling process, but do not assess whether and how the IFAD country strategy and portfolio is designed, implemented and monitored in a way that systematically focuses on supporting a scaling approach. Depending on the country, scaling involves repeater projects by IFAD, hand-off to government and/or partnerships with other external funders. The Indonesia CSPE notes the importance of knowledge management (KM) for effective support of scaling and all three stress that IFAD monitoring and evaluation approaches do not allow systematic capture of whether or not IFAD-supported innovative programs were scaled up by other partners. For Indonesia and Kyrgyz Republic, the CSPEs record replication of particular programs and approaches in other countries with IFAD support. Scaling performance is rated “satisfactory” in the case of Kyrgyz Republic, “moderately satisfactory” for Indonesia, and “rather insufficient” (translation from French) for Guinea-Bissau.

The project performance evaluation (PPE) of the Egypt rural market development project has a ¾-page section on scaling, under the heading of “Sustainability of benefits.” It credits the project with scaling up well-established farming and market practices, based in part on initiatives under earlier projects. But since the project itself is not particularly innovative nor effective, the PPE notes that the scalability issue was strictly speaking not relevant. Moreover, despite a timely effort to develop an exit strategy under the project, there was no support from the government to include relevant financing for project follow-up in the state budget, despite a request by the Ministry of Agriculture. It rated the project “moderately unsatisfactory” under the scaling metric. There is no consideration in this PPE of whether the scaling issue was addressed adequately in project design, implementation and monitoring.

In sum, IFAD’s evaluation practices reflect the fact that an assessment of scaling is explicitly mandated in its evaluation methodology. By focusing on innovation and scaling by other partners (rather than successive funding by IFAD), the focus of the evaluations is also generally on transformative scaling rather than on transactional scaling by replication. The program evaluations at regional, sector, and country levels also consider to what extent IFAD has supported the transfer of successful project and program experience from one country to other countries. The evaluations consider how system strengthening and knowledge management contribute to IFAD’s scaling efforts, but find these generally limited in scope. In particular, they note the lack of evidence on the extent to which IFAD-supported interventions have been scaled by others after project completion. Aside from these clear strengths, IFAD’s evaluations also show some limitations. The scope and depth of the scaling assessment vary widely across evaluations. Moreover, they tend to focus on specific examples of more or less successful scaling, but do not look at overall portfolios at a country level and do not consider whether scaling was systematically incorporated into the design, implementation and monitoring of country programs or projects. It is also not clear how consistently the ratings are applied under the scaling metric.

World Bank evaluations

The World Bank’s evaluation principles mention scaling only in passing as noted in Section 4. We reviewed four evaluations: three country program evaluations (for Cote d’Ivoire, Pakistan, and Ukraine; all from 2022) and one project evaluation (for two rural development projects in Uzbekistan; 2019).

Two of the country program evaluations (Cote d’Ivoire and Ukraine) make no mention of scaling or replication. The Pakistan country program evaluation notes that the World Bank supported large-scale projects and that a project supporting improvements in the business regulatory environment and capacity in Punjab was replicated in other regions of the country with Bank and IFC support. The evaluation also mentions that the Bank developed a “Strategy to Scale up Renewable Energy” and carried out analytical work on “Scaling Up Rural Sanitation and Hygiene in Pakistan.” However, there was no assessment of the quality or impact of these two initiatives, nor an analysis of whether and how the Bank supported scaling systematically and effectively in Pakistan.

The evaluation of the two rural development projects in Uzbekistan paid some attention to scaling, since one of the projects supported a rural enterprise support effort covering 88 districts in seven regions of the country, based on the experience and capacity that had been created in connection with a preceding pilot project that supported interventions in five districts, also with financing from the World Bank. The evaluation notes that the follow-on project “benefited from the capacity built under the [pilot project] implementation in terms of the experience, incorporated lessons, and existing central project implementation unit structure within [the national agency].” (p. 31/32) The evaluation also reported that the beneficiaries of the project highly valued the scaling up process and especially its highly participatory nature. This attention to the scaling aspects of one of the projects covered by this evaluation is notable, but the evaluation does not comment on whether and how the Bank supported scaling under the second project covered (a water resource management project). Moreover, the evaluation does not identify whether the (scaled-up) rural enterprise support project fully covered the needs of the country, or whether further scaling was needed; and, in the latter case, how the project supported the further scalability of the approach beyond its lifetime. The evaluation does note that sustainability of the project benefits is at risk.

In sum, World Bank evaluations generally do not address scaling in a significant way, if at all. The exception in the case of a project that specifically was designed to scale up a prior pilot project.

Conclusions and recommendations

This paper explained why evaluation and evaluation guidelines are potentially important instruments for mainstreaming scaling and provided an indicative framework for how evaluation guidelines could address scaling. It then reviewed the publicly available evaluation guidelines for OECD-DAC (the EvalNet guidelines for evaluation and the DAC Peer Review methodology), for MOPAN, and for 18 large bilateral and multilateral official funder agencies. Its analysis concluded with a review of scaling in 17 program and project evaluations for four funder organizations.

For the OECD-DAC guidelines and the MOPAN methodology, the paper finds that while there are occasional references to scaling, the guidelines do not focus effectively on this important aspect of development effectiveness, let alone provide helpful guidance to evaluators on how to assess an agency’s approach to scaling and its performance on scaling for specific projects or programs. This represents a missed opportunity since it leaves the funder organizations and their governing bodies without information on whether and how they support scaling. It also means that OECD-DAC and MOPAN fail to influence and support the evaluation units of official funder organizations and, indirectly, the efforts of the funder agencies to mainstream scaling, since many of the evaluation guidelines of the individual funder agencies are based on the OECD-DAC guidelines.

Our analysis further found that for ten funder agencies, evaluation policies or guidelines do not address scaling; for another four, there is only limited coverage; while for another four agencies, scaling is a central part of the evaluation policies or guidelines, with varying degrees of guidance provided. Overall, it appears that multilateral funders, and in particular vertical funds (funders focused on narrowly defined sectoral or thematic objectives), have been more progressive in focusing their evaluations on impact at scale, compared to bilateral funders. However, even the evaluation guidelines for the four agencies that focus more on scaling do so in highly differentiated ways, lacking comprehensiveness and detail on how to assess the scaling approaches of their agencies.

The paper then reviews 17 actual evaluations of four official funder organizations and finds a wide variety of practices. The experience is mixed: IFAD, not surprisingly given its formal guidance to evaluators, has the most detailed treatment of scaling, but even its evaluations deal with scaling in a less systematic and effective manner than would be appropriate. MOPAN assessments surprisingly frequently refer to scaling, even though the methodology makes no reference to scaling. In the case of OECD-DAC peer reviews and World Bank evaluations, scaling plays a very limited role, if any. In all cases, the evaluation practice would need to be significantly redesigned for it to focus systematically and effectively on scaling.

If evaluation guidelines do not provide guidance on how to evaluate scaling and if scaling is not a focus of evaluations in practice, then management and staff of donor agencies who design and implement projects are offered no learning opportunity and have little incentive to integrate scaling into those projects. This perpetuates the existing bias of projects towards confining their impact solely to what can be achieved within the time frame and resources of a project, rather than simultaneously creating the foundations for future scaling, catalytic change and transformational impact. In the aggregate, the lack of incentives for scaling from evaluations contributes to the inability of each donor’s portfolio to achieve greater impact, and for the sector as a whole to achieve its goals in general, and the SDGs in particular.

Assuming that OECD-DAC and MOPAN members are interested in achieving greater sustainable impact at scale, integrating scaling into their evaluation guidelines can itself be catalytic in incentivizing scaling. To achieve that goal, based on the findings of this paper, we recommend:

- The OECD-DAC EvalNet and Peer Review units, as well as MOPAN, develop guidance documents that focus on scaling in project and program evaluations, with key details on how scaling or potential for future scaling, replication and sustainability can be effectively evaluated. This should include not just questions, but also guidance on how to answer them.

- In preparing these evaluation guidance documents, the OECD-DAC and MOPAN secretariats should draw on the scaling guidance document currently under preparation by the OECD-DAC innovation team.

- The evaluation offices of individual funder agencies should review their evaluation policies and guidelines with a view to integrating scaling more systematically and effectively.

- In preparing these guidance documents, the available literature on scaling and the new OECD-DAC scaling guidance document should be consulted and special attention should be paid to the approach and experience of the four funder agencies that have integrated scaling into their evaluation guidelines (especially GCF, GEF and IFAD).

- More research needs to be done on whether and how evaluations in fact address scaling, with or without appropriate guidelines; what the incremental cost of comprehensively evaluating scaling is on top of other established criteria; and whether and how the incentives and learnings provided by evaluations can be used more directly to support mainstreaming of scaling in funder organizations.

Annex 1: Sources for the official documents of official funder organizations

- AFD (Agence Française de Développement), 2013 https://www.afd.fr/en/ressources/evaluation-afds-evaluation-policy

- GIDE (German Institute for Development Evaluation), 2018 https://www.deval.org/fileadmin/Redaktion/PDF/03_Methoden/DEval_Methods_and_Standards_2018.pdf

- JICA (Japanese International Cooperation Agency), 2014 https://www.jica.go.jp/english/our_work/evaluation/tech_and_grant/guides/c8h0vm000001rfr5-att/guideline_2

- KfW (Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau), n.d. https://www.kfw-entwicklungsbank.de/International-financing/KfW-Development-Bank/Evaluations/Evaluation-criteria/

- AfDB (African Development Bank), 2019 https://idev.afdb.org/sites/default/files/Evaluations/2020-06/Revised%20AfDB%20Evaluation%20Policy%20EN.pdf

- EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development), 2013 https://www.ebrd.com/what-we-do/evaluation-policy.html

- EIB (European Investment Bank), 2019 https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/viewer/Evaluation_Policy_Framework_IDB_Group_en.pdf

- IADB (Interamerican Development Bank), 2019: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/viewer/Evaluation_Policy_Framework_IDB_Group_en.pdf

- UNEG (United Nations Evaluation Group), 2016 http://unevaluation.org/document/detail/1914

- GIZ (Gesellschaft für international Zusammenarbeit), 2022 https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2022-en_GIZs-evaluation-system-basic-aspects.pdf; 2018: https://reporting.giz.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/03/GIZ_EVAL_EN_evaluation-policy.pdf

- USAID, 2020 https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/Evaluation_Policy_Update_OCT2020_Final.pdf

- ADB (Asian Development Bank), 2016 https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/32516/guidelines-evaluation-public-sector.pdf

- World Bank Group, 2019 https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/sites/default/files/Data/reports/WorldBankEvaluationPrinciples.pdf

- GCF (Green Climate Fund), 2023 https://ieu.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/gcf-evaluation-guidelines-web.pdf

- GEF (Global Environmental Facility), 2020 http://web.undp.org/evaluation/guideline/documents/GEF/TE_GuidanceforUNDP-supportedGEF-financedProjects.pdf

- IFAD (International Fund for Agriculture and Development), 2022. Volume 1 https://ioe.ifad.org/documents/38714182/45756354/IFAD-2022-IFAD-EVALUATION-MANUAL-COMPLETE-def.pdf/05bd1a53-26ee-c493-b1a0-2fc3050deb80; Volume 2: https://ioe.ifad.org/documents/38714182/45756354/IFAD-2022-02-PART-EVALUATION-MANUAL-COMPLETE-ENG-04_FINAL.pdf/07534c51-37ca-9b43-f870-3915f5e1f795

- UNDP (United Nations Development Program), 2021 http://web.undp.org/evaluation/guideline/documents/PDF/UNDP_Evaluation_Guidelines.pdf

Annex 2: Sources for program and project evaluations of selected official funders

OECD-DAC Peer Reviews

- United Kingdom https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-development-co-operation-peer-reviews-united-kingdom-2020_43b42243-en.html

- United States https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-development-co-operation-peer-reviews-united-states-2022_6da3a74e-en.html

MOPAN Assessments

- Global Fund https://www.mopanonline.org/assessments/globalfund2021/MOPAN_2022_GlobalFund_PartI_FinalWeb.pdf

IFAD

- Subregional evaluation of countries with fragile situations in West and Central Africa https://webapps.ifad.org/members/ec/119/docs/EC-2022-119-W-P-4.pdf

- Rural enterprise development https://ioe.ifad.org/documents/38714182/47789549/Project+cluster+evaluation+on+rural+enterprise+development/4a23dbc8-1e46-3a25-07ae-fb995a4667ba

- Guinea-Bissau https://ioe.ifad.org/documents/38714182/48400197/Guinea-Bissau+CSPE+Report/205d304a-713b-aa7d-202d-2cfdafe2a323

- Kyrgyz Republic https://ioe.ifad.org/documents/38714182/48972120/Kyrgyz+Republic+CSPE+Report/432d02c9-9792-6bf8-c12b-6fb79b5c563f

- Promotion of rural incomes through market enhancement https://ioe.ifad.org/documents/38714182/47836227/Promotion+of+Rural+Incomes+through+Market+Enhancement+Project/77cfe0b9-56e0-0a23-3ccb-94a80ba29951

World Bank

- Cote d’Ivoire https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099165001252324868/pdf/BOSIB0e6f4f0ae0e10aa04019934a6733b4.pdf

- Pakistan https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/265831497751223503/pdf/PAKISTAN-PLRNEW-05242017.pdf

- Ukraine https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/evaluations/world-bank-group-ukraine-2012-20

- Uzbekistan water and irrigation projects https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/sites/default/files/Data/reports/ppar_uzbekistanirrigation.pdf

Annex 3. Excerpts on scaling from evaluation guidance documents

Box A1: Scaling up in the evaluation policy and guidance documents of ADB, GIZ, USAID, and the World Bank Group*ADB: ADB’s Guidelines for the Evaluation of Public Sector Operations has a strong statement on the need to assess the scalability of projects: “In particular, an assessment should also include the potential for scaling-up projects with innovative features. A project’s approach to addressing an identified development constraint should be assessed relative to existing good practice standards. Innovative and transformational project design is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a highly relevant rating.” (p. 6) It further notes that “[[t]he assessment can also include a discussion of any efforts to scale up and replicate successful features of the project that were not previously evident in other projects in the country or in communities that have been made during or after project implementation.” (p. 24) The document notes that the evaluation approach is based on OECD-DAC evaluation principles. GIZ: GIZ’s Evaluation Policy document refers twice to scaling: first, by noting that evaluations can help “to analyse the conditions required for … scaling up” (p.5) and, second, by observing that ”[p]rojects often have to deal with ‘wicked problems’ for which there is no effective, long-term, scalable solution. They therefore need to find creative and flexible solutions for adapting to the context and to the problem in hand.” (p.12). GIZ’s Evaluation System document notes that projects are selected for in-depth evaluation if, inter alia, they offer “the potential … for widescale replication.” (p. 12) The same document also highlights that RCTs can provide the basis for decisions “as to whether scaling up would be effective, and if so in what form.” (p. 15) This document also mentions that GIZ evaluations apply OECD-DAC evaluation criteria. USAID: USAID’s Evaluation Policy document notes that “[e]valuations that are expected to influence resource allocation should include information on the cost structure and scalability of the intervention, as well as its effectiveness.” (p. 8) It further requires that “[e]ach Mission and Washington Operating Unit must conduct an impact evaluation, if feasible, of any new, untested approach anticipated to expand in scale or scope through U.S. Government foreign assistance or other funding sources (i.e., a pilot intervention).” (p. 10) The document mentions that it is based on OECD-DAC evaluation principles and guidance. The World Bank Group: The World Bank Group’s Evaluation Principles document notes that “independent evaluations and demand-driven self-evaluations should be prioritized by learning needs as determined by (among others) the innovative nature of the intervention, existing knowledge gaps, and the potential for replication or scaling up.” (p. 12) This document also refers to the OECD-DAC evaluation criteria. * Note: For document references see sources for Annex 1. |

Box A2. Scaling in GCF evaluation guidelines*While not providing detailed guidance on how to assess scaling, the GCF’s Operational Procedures and Guidelines for Accredited Entities’ Evaluations focuses on scaling in various ways:

* Note: For document references see Annex 1. |

Box A3. Scaling in GEF evaluation guidelines*The GEF’s Guidance for Conducting Terminal Evaluations of UNDP-Supported, GEF-Financed Projects focuses on scaling in various ways:

* Note: For document references see Annex 1 |

Box A4: Scaling in IFAD evaluation guidelines*The IFAD Evaluation Manual (Volume 1) provides guidance on how to assess scaling aspects as follows:

* Note: For document references see Annex 1. |

Box A5. Scaling in UNDP’s evaluation guidelines*The UNDP Evaluation Guidelines also focus on scaling:

* Note: For document references see Annex 1. |

Box A6: Excerpts from OECD-DAC peer review reportsGermany “Innovation and adaptation: Capabilities exist to introduce, encourage, measure and scale up innovation in development co-operation. (Yes) First steps undertaken towards building a culture and capabilities across BMZ, KfW and GIZ. Innovation could be introduced more firmly on the political agenda of conversations with partner countries.” (p. 75) “The plans for starting a new DigiLab fostering multi-stakeholder arrangements to scale-up existing innovations and jointly develop new innovations are a promising approach …. Yet, it will be important that innovation is promoted beyond digitalisation, which will require a holistic approach across the German system — from incentivising individual staff to spot and scale up innovations and fostering an innovation mindset, institutional structures and work atmosphere to strategic planning, procurement and engaging in new partnerships to engage in radical thinking and approaches.” (p. 77) Switzerland “An overall budget planned for four years, excellent forecast information, and multi-year funding agreements provide implementing partners with the necessary predictability to design and execute long-term projects. In addition, programming and budgeting are flexible enough at the country and project levels to adapt to evolving needs and focus on achieving long-term results in countries …. Switzerland also provides seed funding for innovative projects with the private sector. Global programmes are a useful tool to further scale-up innovation.” (p. 18) “Switzerland is partnering with a broad range of actors. While some partnerships are strategic, presenting synergies with the different funding channels, others tend to be more instrumental in the sense that they are focused on implementing Switzerland’s projects. This represents a missed opportunity to leverage each actor’s added value to reach higher-level objectives….The objectives of multilateral co-operation are clear: they aim at complementing bilateral co-operation, while scaling progress and creating global norms.” (p. 41) “Switzerland has tools to foster and scale up innovative ideas, whether in terms of new partnerships, funding mechanisms or technologies… Even though replicability and scale-up are part of the projects’ selection criteria, both within the global programmes and the REPIC Platform, replication remains a challenge.” (p. 62) United Kingdom A powerful combination of funding instruments, expertise, and political and technical networks allows the United Kingdom to achieve breadth, depth and scale in its partner countries and to draw on its country programmes to bring about broader reforms.” (p. 18) “There is scope to better communicate the United Kingdom’s full offer to the private sector and to formally build a continuum of support, ranging from early technical assistance to investment at scale.” (p. 48) “DFID was one of the first donors to advocate for new solutions to development challenges, backed by some of the first challenge funds. Its innovation portfolio has now reached significant scale, breadth, depth and maturity and a number of ideas, such as mobile finance, have been brought to scale with impressive results.” (p. 66) “Finally, results are at the core of the United Kingdom’s partnerships with multilateral organisations. In 2016, DFID committed to ‘follow the outcomes’ by further developing and scaling up the use of payment by results approaches when engaging with partners.” (p.85) “In its ambition to improve the international humanitarian system, DFID provides flexible, predictable and multiannual funding, helps its partners respond more effectively to emergencies, supports innovation and delivers a cash-based response at scale.” (p. 99-100) United States “As a leader on localisation, the United States should ensure that principles of development effectiveness are central to how it delivers on its objectives, in particular by:…supporting more effective partnerships to implement localisation at scale – with all its partners – and notably through increasing support to partner governments and more core support to local civil society.” (p. 11) “Embedding programmes within national systems can provide a powerful route to sustainability as well as systemic, scalable change beyond the project level… The MCC@20 process could be used not only by MCC but across the interagency to consider the hard questions of how to scale up a successful development model that puts country ownership at its core so that it is a system fit for the challenges of tomorrow.” (p. 38-39) * Note: For links to the review reports see Annex 2. |

Box A7: Excerpts from MOPAN assessment reportsUNDP “As found in the evaluation of the Strategic Plan 2018-21, UNDP’s capacity to embed, leverage and scale up innovation is constrained by limited risk appetite, lack of stakeholder support, inadequate financial resources, insufficient flexibility in rules and regulations, and shortcomings in its monitoring and evaluation and knowledge management functions.” (p. 32) “UNDP has yet to ensure the use of the captured lessons to improve results, catalyse and scale up success and innovation, and accelerate the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.” (p.157) “A main and recurrent source of criticism in most country-level evaluations regards UNDP’s fragmented portfolios, rendering it difficult to move from short-term, small-scale, one-off stand-alone downstream interventions to scalable, transformative longer-term solutions and/or upstream policies.” (p.173) UNICEF “UNICEF’s global strategic partnerships are both a challenge and an opportunity. Its operating model depends on partnerships with other UN entities, businesses, civil society, and children and young people. But its approach to partnership has often focused on its own programme implementation, fundraising and advocacy, rather than on leveraging resources for children and catalysing large-scale changes for children. To this end, UNICEF has prioritised global strategic partnerships with transformative potential to accelerate global progress towards SDG targets, on health (e.g., Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance), education (Global Partnership for Education, Education Cannot Wait), and nutrition (Scaling up Nutrition Movement). As mentioned above, it has also developed global strategic partnerships aimed at transformational change with UNDP, WHO, WFP and UNHCR..” (p. 37) “There are some examples … of low- cost unit interventions that have been scaled up to reach several beneficiaries, including through the implementation of networks of volunteers and a training the trainer approach.” (p. 69) “While the DER Development Effectiveness Review] found that UNICEF has successfully brought programmes to scale, it also identified the need to ensure medium to long-term financial sustainability through leveraging sustainable financing from governments, the private sector and civil society.” (p.69) “In Eastern and Southern Africa (ESARO), for example, UNICEF is looking to engage with the private sector beyond fundraising to partnerships for innovation and scaling up innovation. However, it is not fully achieved.” (p.96) Global Fund “While the Global Fund’s Strategy 2017-22 does list the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to which it contributes along with the disease-specific objectives with which it is aligned, the explicit linkages between its internal measures and the SDGs are still being developed. … Along with the SDGs, the strategy also notes its alignment with global disease-specific objectives such as:

However, the direct and precise links between the Global Fund’s results and these greater goals are not yet clearly or completely defined. Key informant interviews reveal that those linkages will be developed in the next iteration of supporting documents for the 2023-28 strategy, which will include the development of an overarching M&E framework.” (p. 14) “The TRP [the Global Fund’s Technical Review Panel] also considers if the proposed interventions will scale up programmes needed to improve access to prevention, care, and treatment services among the key and vulnerable populations disproportionally affected by the three diseases.” (p. 63) “There have nonetheless been gains in scaling up service coverage, including for those who face discrimination and/or other structural barriers, in part facilitated by Global Fund support for technology and service innovations and interventions targeted at KPs [key populations]. However, the factors driving observed inequities often do not receive sufficient attention in grant and programme design, and wide variations in health service access and health outcomes still exist within and across countries.” (p. 114) *Note: For links to the assessment reports see Annex 2. |