Acknowledgements

The Scaling Community of Practice (SCoP) and the authors are indebted to the many colleagues from the funder partner organizations that participated in this Initiative with case studies and in commenting on the findings. The authors received helpful comments on the Synthesis Report from the SCoP’s High-Level Advisory Group, the SCoP Executive Committee, a special Steering Group for the analysis of mainstreaming scaling by foundations, and from participants in various dissemination events. The authors and the SCoP wish to express their special thanks to the Agence Française de Développement and to Eric Beugnot for the financial support extended to make this Initiative possible. They thank Charlotte Coogan and Leah Sly for their editorial support in finalizing this paper. The authors bear sole responsibility for the contents of the paper.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE

I. The Mainstreaming Initiative

Even before the recent dramatic cutbacks in bilateral official assistance, it was clear that scaling, when defined only as committing more financial resources, was not going to be the margin of difference. A fundamental shift in approach was needed to achieve sustained development and climate action outcomes commensurate with global needs, requiring a shift from defining scaling as more resources or solely as bigger numbers (transactional scaling) to an approach that targets addressing problems sustainably and at the scale that countries face (transformational scaling). To do this requires a wholesale change from one-off projects targeting short-term outputs to putting in place long-term solutions whose impact is sustainable with domestic resources and institutions. To effect these changes requires, among other things, changing how successful development is measured; making changes in project design and approval criteria that integrate scale and scalability; incorporating actions to catalyze scaling beyond project end; establishing additional incentives and performance metrics that emphasize scaling; and adapting monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning systems to reflect these changes.

Based on a comprehensive Synthesis Report, this policy brief summarizes the central findings and recommendation emerging from a three-year action-research Mainstreaming Initiative undertaken by the Scaling Community of Practice (SCoP) looking at the extent and ways in which the policies and practices of major international funders are rising to this challenge. The centerpiece of the Initiative was 28 detailed case studies looking internally at a wide range of funders to determine the ways in which these funders’ policies and procedures contribute to, or inadvertently impede, the achievement of sustainable outcomes that match the scale of the needs and problems they address.

The 28 case studies include official multilateral and bilateral agencies, vertical funds, innovation and research funders, private foundations, and large international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) that fund development and climate action. The case studies and special papers are posted on the SCoP’s website along with the Synthesis Report. Each case study was produced in collaboration with senior staff of the organizations involved and reflected a willingness on the part of those organizations to take a hard and critical look at their own operations. While hardly a representative sample, these organizations represent a broad and significant array of forward learning organizations and offer, we believe, important lessons regarding how they improve their own practices and inform the practices of others.

The initiative focused on funders because their practices strongly shape the actions of other key actors and can catalyze wider change. Each case study focuses on the following questions:

- To what extent have funder organizations mainstreamed a systematic focus on scaling?

- Which key dimensions of scaling should funders prioritize and support?

- What factors enable or drive the mainstreaming of scaling within funder organizations?

- In which areas have funders made greater progress, and where has progress been more limited?

- What are the principal challenges encountered?

- What lessons emerge for funders seeking to mainstream scaling?

In addition to the case studies, the Initiative included a number of cross-cutting research efforts to provide practical insights regarding: (i) scaling fundamentals, (ii) recipient perspectives, (iii) the relationship between scaling and localization, (iv) evaluation policies and practices of official funders, (v) a tool for tracking the funders’ efforts to mainstream scaling, (vi) the relationship between scaling and country platforms, and (vii) deep-dives on the mainstreaming experience of foundations and of agri-food and education funders.

II. Support by Funders for Scaling: Opportunities and Gaps

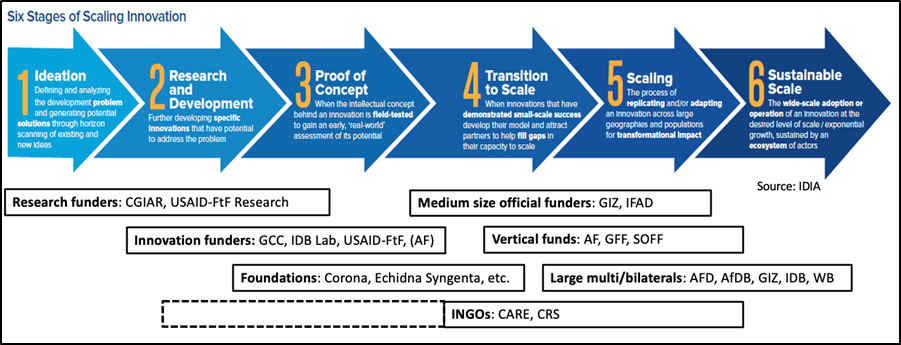

The case studies demonstrate that funders operate at different points along the scaling pathway — from ideation and research and development to transition to scale, scaling, and sustained operation at scale (Figure 1, next page). While funders exist at all stages, major gaps persist in practice, especially in stages 5 and 6 (scaling and sustainable operation at scale). These gaps are primarily due to weak coordination and handoffs between early- and later-stage funders. Moreover, funders that could serve as intermediaries, with the intent to accompany systems actors on the entire journey to scale, generally do not have access to funds to bridge the gap thereby creating the well-known “Valley of Death”.

Figure 1: Stages at which funders could support scaling, within their mandates and resources

Early-stage funders, including innovation and research funders and some foundations, provide some of the most instructive cases of mainstreaming reflecting the fact that many of these funders were established with the explicit expectation of catalyzing impact at scale. Large official funders have the capacity and mandate to finance later-stage transformational scaling but often lag in operationalizing that capacity primarily due to reasons of longstanding institutional mechanisms, incentives and institutional culture, in particular their focus on one-off project funding. Vertical funds operating in particular development and climate areas (such as agriculture, health, weather observations, etc.) and INGOs help to bridge this divide when they partner effectively with large official funders, but this continues to be the exception rather than the rule in the absence of long-term funding commitments and/or coordinated action by all funders to cooperate in supporting the scaling pathway for its duration.

The remaining sections of this Brief unpack some of the Initiative’s findings by looking at (i) good (“transformational”) scaling practices that funders should support; (ii) the factors that allow funders to mainstream support for these practices into their operational approaches; (iii) how funders’ mainstreaming experience differs by funder category; and (iv) some overarching lessons.

III. Applying Transformational Scaling Practices

The report identifies a set of good scaling practices, examines to what extent study organizations have adopted these practices, and highlights the challenges involved.

A central finding of the Initiative is the need for funders to prioritize transformational scaling rather than transactional scaling. Transformational scaling focuses on achieving sustainable outcomes at scale through systemic change, continued scaling beyond project life, and operation by domestic actors using domestic resources. In contrast, transactional scaling emphasizes larger volumes of funding and/or greater numbers of people or places reached by more or larger one-off projects — a pattern that remains common, particularly among large official funders.

Over 11 years of operation, eight Annual Forums, more than 200 webinars, and a wide array of field-based case studies, the SCoP has identified a set of eight good practices associated with transformational scaling. The case studies carried out under the Mainstreaming Initiative include multiple examples of these good scaling practices in action and illustrate the practical challenges funders face when trying to implement each of these practices.

- Initiate scaling from the beginning (“start with the end in mind”). It is not sufficient for funders to focus on scaling at the end of an innovation process or when exiting a project. There needs to be a clear vision from the outset of what successful scaling looks like. The conditions that allow scaling to happen – primarily alignment with domestic priorities and resource and implementation constraints at scale – have to be addressed from the beginning of the scaling pathway. Starting with the end in mind often requires early engagement with delivery, regulatory, or market actors that funders do not traditionally involve at the design stage. Otherwise, innovations are often not scalable or require substantial modification before scaling can proceed at considerable cost, time delay, and effort. Most innovation funders, vertical funds, as well as some INGOs and foundations, have learned this lesson, often adopted iteratively over time rather than in a clear sequence or all at once.

- Incorporate scalability criteria and assessment into all stages of scaling: innovation, project and program design, piloting and implementation. A systematic assessment of scalability helps guide, monitor, and evaluate the design and implementation of the scaling process by assessing the enabling conditions of scaling – demand, costs, incentives, financing, capacity, political support, etc. – and drawing attention to issues such as complexity; potential opposition; ease of production and delivery by suppliers; ease of adoption by end users; unit cost; and availability of a “funder at scale.” Scalability assessments tend to be most useful when revisited over time and used to adjust strategy, rather than treated as one-off design tools. Various scalability assessment tools have been developed, including some by individual funder organizations, but so far adoption has been largely by innovation funders and foundations as opposed to larger project funders.

- Integrate support for systems change with scaling. Achieving impact at scale requires funders systematically to identify and address institutional, policy, and political constraints alongside scaling investments to increase the probability of successful scaling and impact. Smaller funders often lack the mandate or capacity to engage in systems change, while larger funders frequently fail to align systemic reform with investment financing or sustain engagement over time. A few vertical and knowledge-focused funders stand out for persistently supporting systemic change to enable transformational, sustainable impact at scale.

- Explicitly address equity and inclusion and anticipate unintended consequences. Scaling efforts can unintentionally reinforce inequality or create other unintended consequences such as adverse environmental impacts. Increased inequality is driven by the fact that reaching marginalized and vulnerable groups often requires greater time, effort, and unit cost. Funders should make equity tradeoffs explicit; balance breadth, depth of impact, and equity considerations; and target optimal — not maximum — scale. While many funders espouse equity goals, few systematically integrate these tradeoffs into their scaling objectives and funding decisions.

- Double down on country ownership and localization. Transformational scaling depends on domestic actors — government, business, and civil society — owning the vision of impact at scale, the solutions and the scaling pathways, and having the capacity and resources to sustain them. While many funders support localization, smaller funders often lack in-country presence, and larger funders are constrained by transactional project models. Localization too often continues to be interpreted as consultation rather genuine changes in historical power dynamics, and top-down rather than inclusive. Country-led cooperation mechanisms for national and international stakeholders – sometimes referred to as “country platforms” – can help align interests and plans, coordinate resources, and support long-term scaling with system change. However, they require institutional support structures, sustained resourcing, strong incentives, and staff mandates aligned with transformational impact, all of which requires the platform participants, including the funders, to focus systematically on scaling approaches.

- Invest in partnerships with other funders. Because no single funder spans the full scaling pathway nor is best placed to undertake all the tasks needed at a given scaling stage, effective scaling requires partnerships — often through country platforms, collaborative financing mechanisms, and coordinated handoffs across scaling stages. While some of the organizations we profile in this study are now pursuing partnerships more aggressively, all are challenged by the often unanticipated costs of developing and maintaining partnerships, which take time, resources and a willingness to harmonize processes, to share control, and to co-brand. This is true even when the handoffs are between innovation units and project-funding windows within the same organization. Depending on the preferred scaling pathway, critical partnerships can be with host government agencies, other external funders, local NGOs, and/or private sector actors; and each of these partnerships has its own complexities.

- Embed scaling in monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning (MEAL) systems. Effective scaling requires monitoring not only outputs but also impacts, enabling conditions, and the scaling process itself. Learning from experience has to be used to revise and update objectives and scaling strategies; support adaptive, flexible management; and ensure accountability. While some innovation and smaller funders have adopted more scaling-aware MEAL approaches, many funders still prioritize project delivery metrics over indicators of process and systems change and of transformational impact at scale, and few innovation funders track progress over time in scaling and institutionalization.

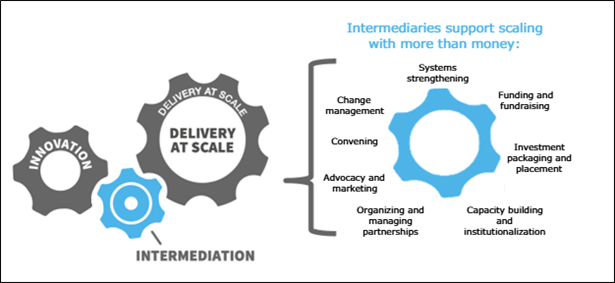

- Elevate and strengthen intermediary roles. The lack of effective intermediation across the scaling pathway contributes to the stubborn persistence of unscaled pilots and the “Valley of Death” for promising innovations and interventions. Funders can be of great assistance when they go beyond traditional project financing and support local intermediaries – or use their own good offices – to broker handoffs across scaling stages, convene partners, and strengthen coordination structures, such as country platforms (Figure 2). When this role is weak, limited to technical support, or overly transactional, gaps persist along the scaling pathway, reinforcing the “Valley of Death” for promising innovations and interventions.

Figure 2. The manifold functions of intermediaries

IV. Mainstreaming Transformational Scaling Practices in Funder Organizations

Based on the case studies and a related study of the published and unpublished literature, the Initiative developed a Mainstreaming Tracker Tool (MTT) to assess and guide progress by funders in mainstreaming a systematic approaches to scaling. Among the factors highlighted in the MTT, the case studies suggest the following nine factors are the most salient drivers of mainstreaming scaling:

- Leadership must drive scaling. Embedding scaling across a funder organization requires leadership at all levels, but sustained change must be led from the top. Governing bodies and chief executives need to set a long-term vision for transformational impact, ensure continuity through leadership transitions, and translate commitments to scale into operational practice. While many funders emphasize impact at scale, this often remains aspirational or merely transactional and is not matched by changes in incentives, resources, and management systems. Clear direction, accountability, and support are essential to move from rhetoric on scaling to transformational action. This challenge is most pronounced in the official multilateral and bilateral funders.

- Corporate Mission, Vision, Goals and Definitions Have to Focus on Transformational Impact at Scale. While many funders now reference impact at scale in their mission and vision statements, few — mainly vertical funds — define clear, measurable long-term impact goals and pathways to achieve them. Broad mandates make this more challenging, but evidence shows that the clearer and more specific the institutional commitment to achieving specific sustainable outcomes at scale, the more effectively these commitments are reflected in operational practice. Case studies also reveal persistent confusion and multiple definitions about what “scaling” means within an organization — often conflated with larger or more numerous projects rather than systemic, lasting change — highlighting the importance of clear, shared institutional definitions.

- Financial and Operational Instruments, Policies and Practices Have to Support a Scaling Approach. Funder organizations have diverse financial and non-financial instruments that can support – or inadvertently undermine – pathways to transformational impact. Longer time horizons are particularly important for achieving impact at scale, yet long-term, multiphase programmatic financing remains underused. Operational policies, appraisal criteria, monitoring and evaluation systems must explicitly incorporate scaling considerations and preconditions, shifting the focus beyond short-term project outputs toward long-term, sustainable, and scalable outcomes supported by the needed enabling conditions. Most funders have yet to integrate scaling fully into their operational policies and processes.

- Dedicated Organizational, Staff and Budget Resources Have to Be Committed to Scaling. Funders that have most effectively mainstreamed scaling have invested in dedicated units, staff, and budgets to build capacity, incentives, and a culture supporting transformational scaling. While central support units are often necessary initially, scaling must ultimately be owned by front-line operational staff and their managers. The case studies demonstrate that managers and staff feel overloaded with “unfunded mandates” imposed from the top without adequate resources and prioritization and often resist the effort to add what they see as yet another priority – scaling – to what they already consider as an excessive set of tasks. Those organizations that have been able to mainstream scaling effectively had access to dedicated, long-term resources for mainstreaming scaling in their organizations (in the form of endowments, external funder support, or earmarked internal funding).

- Decentralization Can Support Scaling But Is Not a Panacea for Localization. Many funders have realized the importance of localization and especially the larger ones have decentralized their operations by placing staff in country or in regional hubs. This closeness to the client helps with consultation and coordination, but it does not guarantee that funder staff pursue scaling and localization effectively, especially when institutional priorities, resources and incentives are not aligned with national priorities and locally defined needs. Clear institutional direction, aligned incentives, delegated authorities, and resources are needed to ensure decentralized teams support nationally driven, locally defined scaling pathways.

- Analytical Tools, Learning, and Knowledge Are Important for Mainstreaming Scaling. While many funders have adopted or developed analytical tools, training, and advisory support to enable scaling, these are effective only when paired with clear incentives and when the overall culture has centered on scaling. Experience shows that tools and learning capacities — though important — are insufficient on their own; staff use them consistently only when scaling is embedded in performance expectations, resourcing, and decision-making. In fact, in several cases of smaller funders, a shift in organizational culture was successful in driving mainstreaming with little or no investment in frameworks and tools.

- Monitoring and Evaluation Must Support the Mainstreaming Process. In addition to assessing and informing programmatic efforts to achieve sustainable outcomes at scale (good scaling practice #7 above), monitoring and evaluating have been used effectively by some organizations to assess, guide, and drive their internal change processes by analyzing the extent to which strategies for organizational change are having the desired effect of institutionalizing a systematic focus on transformational scale.

- Mainstreaming Must Be Planned and Sequenced with a Focus on Creating the Right Incentives for Scaling. While mainstreaming ideally follows a planned, phased approach — beginning with leadership commitment followed by clear definitions, alignment of mission, development of policies, allocation of resources, and adoption of tools — case studies show that such systematic sequencing is uncommon. In practice, organizations advance through iterative learning and adaptation rather than fixed blueprints. Strong leadership, clarity of vision, persistence and continuous learning are the critical enablers throughout the process in line with the Chinese proverb of “crossing the river by feeling the stones”.

- Tensions and Tradeoffs in Mainstreaming Scaling Must be Recognized and Managed. The case studies reveal that funders face tradeoffs and tensions in their efforts to mainstream scaling. These include tradeoffs between quantity and quality, between depth and breadth, between equity and unit cost, and between scaling and other priorities. More often than not, these tradeoffs are ignored, but the cases also include examples where tradeoffs and tensions are considered explicitly and used to inform funder organizations’ scaling agendas.

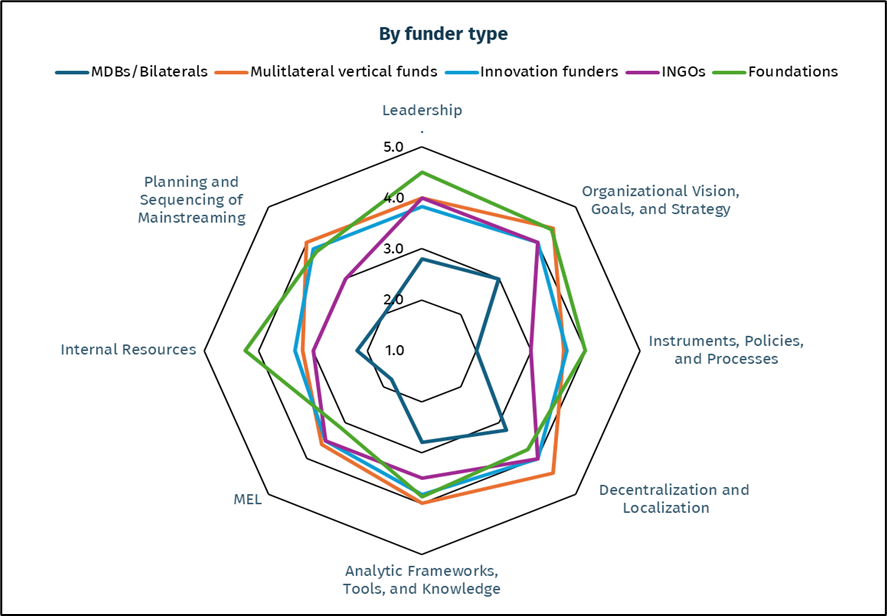

V. Mainstreaming Experience by Category of Funder

The Synthesis Report provides an analysis of findings for five categories of funders plus a separate analysis of Big Bet and open call competitions. Recognizing that the small number of organizations in each category limits the representativeness of the samples, an AI-based analysis of the case studies, drawing on key elements of the Mainstreaming Initiative’s Tracker Tool, broadly corroborates the qualitative findings. Figure 3 summarizes the results of the AI analysis. The following paragraphs add additional insights from the case studies for each of the funder categories.

Figure 3. Mainstreaming score by funder type and factor

- Large multilateral and bilateral funders face the greatest mainstreaming challenges. Despite having the greatest resources and strong mandates to support transformational systems change, large official funders struggle most to mainstream transformational scaling. Case studies show they remain anchored in risk-averse, transactional project models with limited incentives to embed scaling from the outset, while expanding mandates stretch staff and budgets thin. They frequently conflate working at large scale (transactional scaling) with transformational change. When it does happen, scaling tends to occur through follow-on or replicated projects (or replication in other countries and contexts) rather than through deliberate scaling pathways. Incentives to adopt innovations from smaller funders are weak as is internal knowledge management. While successful transformational scaling does occur, it remains episodic rather than systematic, underscoring the urgency of mainstreaming scaling into core operational practice.

- Multilateral vertical funds are strong performers, with some constraints. Vertical funds tend to be among the most effective in mainstreaming transformational scaling, aided by their focused mandates and strong accountability for demonstrable impact. However, case studies highlight constraints related to sustaining leadership focus on scaling, aligning national stakeholders around shared scaling pathways, and mobilizing sufficient resources to meet scale ambitions. Moreover, funding models have created dependence on external funding and not adequately strengthened domestic implementation capacity, so that when such funding declines or is withdrawn, the negative impact is severe. More broadly, experience suggests that the narrower a vertical fund’s focus, the greater the risk of overlooking wider system-level implications of its interventions.

- Research and innovation funders enable early scaling but struggle with handoffs. These funders are designed to generate innovations with the potential for large-scale impact and have traditionally focused on early-stage scaling. Many now support transition-to-scale efforts through grants, evidence generation, capacity building, and advisory support, and increasingly act as intermediaries by brokering partnerships and next-stage financing. However, limited resources and narrow mandates constrain their ability to support broader systems change or sustain handoffs to governments, private sector actors, or large multilateral and vertical funders. Localization and monitoring impact at scale also remain challenges for research and innovation funders, particularly for funders with limited country presence or broad thematic mandates.

- INGOs show strategic progress but uneven uptake. INGOs, such as CARE and CRS, have moved beyond isolated projects to embed scaling within their organizational strategies, frameworks, and internal mechanisms, largely driven by top-down and bottom-up leadership. Both have embraced transformational scaling conceptually and are experimenting with policy integration, market approaches, blended finance, and system-level MEAL indicators. However, mainstreaming remains uneven at country level, where decentralized offices continue to rely on donor-funded project replication. Shifting toward intermediary roles that emphasize systems change and policy engagement is also constrained by lack of funding models, leading to resistance and inconsistent uptake at the country level.

- Foundations are emerging as flexible scaling enablers, with coordination challenges. A growing number of private foundations are rethinking how to contribute to sustainable impact at scale, leveraging their flexibility to make long-term commitments, support intermediation and field building, and provide non-financial scaling support. This shift is most evident among problem-focused foundations and catalytic domestic philanthropies in low- and middle-income countries. Key challenges remain in reducing fragmentation, strengthening collaboration with governments and official funders, and addressing accountability gaps.

- Big Bet and open-call competitions can catalyze scaling, with limits. Some of the public and private funders among our case studies offer relatively large one-time grants for the winner of big bet and open call competitions. These initiatives, especially when they are focused on support for longer-term transformational scale, have produced significant impacts and raised the visibility of the scaling agenda. However, the number of winners is small and there is potential for wasted effort and disappointment among the unsuccessful competitors, notwithstanding the secondary benefits some funders offer in terms of coaching, peer learning, and increased visibility. Despite their larger-than-normal size, Big Bets are typically limited to five years or less in duration and, like other transformational scale efforts, typically require public and private sector resources for the latter stages of scaling and for sustainability.

VI. Conclusions

A summary of the main findings of the Mainstreaming Initiative is contained in the table below.

The main lessons for funders considering mainstreaming?

| Support key transformational scaling practices

· Initiate scaling from the beginning · Incorporate scalability criteria and assessment into all stages of scaling · Integrate support for systems change with scaling · Explicitly address equity and inclusion and anticipate unintended consequences · Double down on country ownership and localization · Invest in partnerships with other funders · Embed scaling into MEAL · Elevate and strengthen intermediary roles |

Put in place key enablers of mainstreaming transformational scaling

· Drive scaling through leadership · Focus vision, goals, and targets on transformational impact at scale · Align operational policies and practices and time horizons with scaling · Dedicate organizational resources and capacity to scaling · Develop analytical tools and knowledge and esp. an incentive and culture for scaling · Go beyond decentralizing operations in supporting localization and scaling. · Use M&E to drive effective mainstreaming · Plan for appropriate sequencing and adapting the mainstreaming process · Manage tradeoffs and tensions transparently |

While these lessons can be adopted by funders regardless of size or type, there are some measures that can best be undertaken by the funder community as a whole or by coalitions of funders. They include the following:

- Integrate scaling into the global development effectiveness agenda.

- Create formal coordination mechanisms and institutions to facilitate linkages between small funders, innovation funders, and larger funders.

- Invest greater resources in creating and strengthening the remit and capacity of inclusive country-led and regional platforms.

- Invest more resources in intermediary organizations and functions.

- Integrate scaling into widely used MEAL frameworks, such as the OECD-DAC evaluation guidelines, and evaluate long-term impacts of scaling efforts.

Call to Action. The Scaling Community of Practice (SCoP) calls on governments, development and climate funders, philanthropies, and implementing partners to commit to a Scaling Campaign for 2026 – 2030. Amid a deepening development and climate finance crisis, business-as-usual is no longer viable, and transformational scaling must move from aspiration to standard practice. This five-year campaign calls for concrete action to reform policies, incentives, financing instruments, and accountability systems so that proven solutions are systematically taken to scale and sustained — delivering impact commensurate with the scale of today’s challenges.