EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A. Introduction

Despite considerable efforts to promote innovation in the agricultural sector, a significant amount of technology either remains on the shelf or is not effectively scaled to reach its intended beneficiaries – the farmers and marginalized communities it is meant to support. This is true across publicly funded programs and projects, even though the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and other donors prioritize striking a balance between fostering innovation and expanding stakeholder access to technology and innovation. Agricultural innovation has unique attributes and public good characteristics with distinct implications for technology management, dissemination, and scaling, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

The twenty-one Feed the Future Innovation Labs (ILs) managed under USAID’s Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) provide a uniquely suitable structure for examining the challenge of agricultural technology management and dissemination, due to their broad scope of crops, livestock, and policy areas, as well as their wide range of collaborating partners that could foster greater scaling of investments in agricultural technology. In particular, key scaling pathways and accompanying mechanisms and frameworks exist to disseminate agricultural technology, with gaps and challenges that could be addressed through legal approaches and coordination among partners. Based on legal analysis, interviews, and case studies, the study highlights common challenges in intellectual asset management and scaling as well as innovative dissemination strategies among the ILs, leading to recommendations on how to strengthen agricultural technology dissemination and scaling and suggestions for developing a tailored USAID policy on management of agricultural technology.

B. Study Objectives

The primary objective of this study is to assess how agricultural technological innovation developed by USAID-supported ILs is managed and scaled to reach local partners and end users to inform development of a USAID policy on agricultural Intellectual Assets (IAs). The aim of the proposed USAID guiding framework will be to ensure a balance between maintaining incentives for further innovation by ILs and their partners while fostering broad access to technologies. Such a policy framework must recognize the wide range of applicable technologies and different dissemination or scaling pathways for agricultural IAs as well as the role of intellectual property rights (IPR). Seeking IPR for agricultural technologies has different dimensions– it can fuel innovation and encourage dissemination but, depending on how it is managed, it can also limit opportunities for scaling due to the capacity and reach of the IL partner and the technology in question.

C. Background

At present, neither USAID nor university policies are designed to consider the unique nature of agricultural technology with regard to IA management and dissemination. Most agricultural technologies are not protected under formal IP, due in part to the fact that, in the agricultural sector, technology is not always clear-cut or easily marketable or commercialized. As such, agricultural research and innovation tend to fall within the category of “public goods,” which are central to addressing food insecurity in developing countries and require different strategies for their dissemination and uptake. The policy void has left donors without a clear system for tracking investment in agricultural technology and has put ILs and their partners in a position to determine individual dissemination strategies without benefitting from shared learning.

D. Legal Framework Governing Intellectual Assets Developed by Innovations Labs

The Bayh Doyle Act (BDA) and its implementing regulations lay the foundation to claim IPR on federally-funded technologies. This is complemented by the Automated Directives System Chapter 318 (ADS 318), which sets out the policies and procedures on intellectual property (IP) developed under USAID programs. Both the BDA and ADS 318 empower universities to claim ownership over federally funded inventions, provided that USAID is given a use right to those inventions. Universities’ rights on the new invention are not absolute and are subject to certain rights and restrictions, such as invention disclosure, ownership, commercialization and licensing, and revenue sharing. Universities have their own policies on IP management, which are not specific to ILs, that govern technologies they develop. Overall, BDA, ADS 318, and university policies tend to prioritize commercialization of IP in specific sectors, such as engineering and pharmaceuticals, with little focus on agricultural innovation, which has left a policy lacuna for management of agricultural technology.

E. Innovation Lab Practices on Intellectual Assets Management and Dissemination

IL approaches to technology management and dissemination center around different forms of IAs0F0F[1] developed by ILs, their scaling pathways, and different legal and institutional considerations based on these factors, emphasizing the need for adopting a flexible approach to IA management and informing recommendations for Feed the Future crop improvement, research, and technology scaling programs.

Research and Development within USAID’s Feed the Future is classified into three clusters: (1) plant and animal improvement research, (2) production systems research, and (3) social science research. Out of these three clusters, the main research outputs or technologies produced by the ILs fall within five key categories: (1) improved varieties, (2) research publications, (3) digital assets, (4) novel devices and processes, and (5) animal vaccines. Some IAs could be legally protected as patents (including plant patents), copyrights, or trademarks. ILs do not typically pursue IP protection but have done so in instances where the IA has high commercial value. USAID has also developed a Performance Indicator Reference Sheet (PIRS) framework for GFSS which tracks the progression of new or significantly improved technologies, practices, and approaches from R&D to update by stakeholders, which has been useful for tracking outputs but is not nuanced enough to ensure effective dissemination.

Legal issues raise important considerations, both regarding technology development and dissemination, and they inform tools for dissemination used by partners (e.g., licensing agreements). For example, in the case of improved varieties, licensing agreements can be adapted to take into account the market for the crop or commodity (e.g., soybean vs. groundnut), type of crop (hybrid vs. open pollinated variety vs. vegetatively propagated crop), and scaling pathway (commercial, public, public-private, or community-based). Legal considerations may also relate to the type of technology (e.g., patent, plant breeders’ rights, trademarks) or the partner (e.g., CGIAR Centers governed by CGIAR legal instruments). Lessons are aggregated across IAs and scaling pathways to form recommendations for a policy framework on scaling agricultural technology.

The main dissemination and scaling pathways for the ILs include: (1) commercial, (2) public, (3) public-private, and (4) community-based or civil society-based partnerships. Notably, however, many IAs are transferred in an informal manner. Commercialization is often pursued to fund further research, upscale technology, and create incentives for further innovation and investment by the private sector. Here, legal tools include licensing agreements and contracts. Public pathways can be pursued to deliver technology directly into the hands of farmers or to public sector partners themselves such as NARES; however, resource constraints are an ongoing concern. In this case, one of the main legal instruments is the Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) used by CGIAR Centers to transfer material to NARES. However, challenges faced by the NARES may require additional considerations. Under public pathways, dissemination to farmers may depend upon subsidy programs and extension services. Public-private pathways are common, since they leverage the reach and resources of the private sector to disseminate publicly developed material. MTAs are used at the CGIAR level, and licensing agreements are becoming increasingly prevalent tools used by NARES and, to an extent, CGIAR Centers. Community-based and civil society pathways depend upon local groups such as farmer’s organizations, faith-based organizations and other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to scale up or disseminate technologies; these are mostly informal arrangements. Illustrative case studies were also developed to highlight some of the opportunities and challenges associated with each of these scaling pathways, in addition to relevant legal considerations. These are summarized in Table 1 below.

F. Intellectual Assets Management Policies in other USG Agencies, Donors and Partners

The partners to which ILs transfer IAs – the private sector, CGIAR Centers, and NARES – may have their own rules and policies to guide the dissemination of the technologies received. On the private sector side, companies tend to seek opportunities in which there is sustainable demand for commercializing a technology and a market big enough to justify investment. Companies tend to seek exclusive rights in technology commercialization, mainly so that they can see a return on their investment in branding and promotion, although this can limit access to technologies that are deemed public goods.

On the public side, the main IL partners are international research centers (CGIAR Centers) and national research institutions (NARES). These public institutions have common objectives in agricultural technology dissemination, namely that both want to ensure that innovations have the greatest public good impact possible, although they differ in priorities and approaches. CGIAR Centers share common legal policies and frameworks, including use of the Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA), but they often pursue different approaches to collaboration with the private sector and use of other legal instruments, such as licensing agreements. NARES focus on national systems and typically try to supplement scarce resources. Their objectives have intensified their interest in using legal tools for technology management, such as licensing agreements with the private sector. CGIAR Centers often engage directly with NARES to help disseminate technology, although practices vary by center, crop, and technology. Moreover, the current effort to unify existing CGIAR Centers under the One CGIAR initiative has led to ongoing work on harmonizing CGIAR Centers’ policies regarding technology management, which provides important lessons for the research questions covered by this study.

Table 1: Scaling Pathways, Legal Considerations, and Illustrative Case Studies

| Dissemination & Scaling Pathway | Process / Mechanism | Legal Considerations | Illustrative Case Study |

| Commercial | Private sector actors disseminate technologies (with high commercial value) to end users through markets. | Technologies with high commercial value are more frequently protected under IPR (patents, copyrights, plant variety protection, trademarks). Licensing agreements are often used to transfer technology to the private sector, which can attract private sector investment in IAs leading to wider dissemination. This approach can facilitate innovation in certain types of technology, but it can also leave out critical stakeholders with important development implications. The private sector will have an incentive to disseminate technology as long as it is commercially viable, but this may not reach underserved communities and farmers. | Soybean varieties developed by Soybean Innovation Lab (SIL) and International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) disseminated through licensing agreements with the private sector (varieties not protected under IPR). |

| Public Sector | Government programs (e.g., extension services, input subsidies) can be used to produce and/or deliver an innovation to end users. Other public approaches, such as the public good approach of the CGIAR, are also used to develop and transfer technology. | Dissemination and scaling of public goods involve different partners, including the NARES, and are covered under different legal instruments such as the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGFRA), which has a strong focus on food security, and Material Transfer Agreements used by IL partners such as CGIAR Centers. These approaches recognize a broader pool of technology beyond IPR, since many of the IAs are treated as international public goods, and a role for an expanded set of partners. Challenges may arise in dissemination, which could be partially addressed by deeper engagement with the NARES and other partners. | Digital tools such as the Breeding Analytics Hub and QRLabelR as open-source platform from Innovation Lab for Crop Improvement currently used by NARES for selecting breeding traits suitable for local needs. |

| Public-Private Partnership (PPPs) | Both public and private sectors are leveraged to deliver innovations that meet public needs while ensuring efficiency, innovation, and sustainability. | Given private sector involvement, legal protection (IPR) is more often sought for certain innovations to incentivize private sector interest in the technology. A mix of legal instruments, e.g., licensing agreements, MTAs, can be used to disseminate technology to balance private sector interests with public good. | PICS bags produced by a private manufacturer and distributed with government support (subsidies and extension services) in several West African countries. |

| Community-Based | Community-based pathways use local groups to support the dissemination of technologies and behavior change practices. | Minimal interest in protecting technologies under IPR, although other legal instruments (e.g., licenses) may still be used. | New peanut varieties from Innovation Lab for Peanut being multiplied and distributed through grassroots initiatives supported by farmer groups and NGOs. |

The study also surveyed the IP policies of relevant USG agencies, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Department of Energy (DOE), Department of Commerce (DOC), National Institute of Health (NIH), and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). These also build up on the BDA in terms of ownership and reporting requirements. Some agencies have provided for certain allowable clarifications of the BDA in their IP policies. For example, USDA and NIH have policies governing when an employee-inventor can retain title to IP, which can occur when a contractor waives title. Other USG agencies also have policies related to exceptional circumstances for modifications of funding agreements.

While these agencies fund research to benefit the public, they take an approach similar to the private sector in that policies focusing on commercialization and dissemination of IP are largely business-related. USDA, which also awards funding for agricultural research, has some notable good practices for the development and dissemination of agricultural innovations that could help inform USAID’s policies in this area. One such practice is USDA’s treatment of seed variety development and its work on determining related IP issues.

G. Key Findings and Recommendations

Below is a summary of key findings and recommendations emerging from the study.

Upstream Management of Publicly-Funded IP

- The upstream management of IP (and IAs) directly relates to downstream technology dissemination and scaling. However, legal instruments focus mainly on IP management at the level of the innovation itself without significant focus on dissemination. As this study has found, for agricultural technology, dissemination is often more critical than protection of the underlying technology, and legal considerations related to dissemination should be better integrated into IP/IA policies.

- The BDA is designed to encourage commercialization of innovation, mainly through patenting. However, this approach has limited application in the agricultural sector, where most innovations will not be covered under patents due to either the nature of the technology or the cost involved. As a result, commercialization of agricultural technology requires a stronger focus on dissemination pathways. As the study shows, even when there is a stronger commercial interest and role for the private sector, effective dissemination and scaling will depend upon collaboration with public sector partners, such as CGIAR Centers and NARES.

- At present, IAs and IP developed under Feed the Future projects are not managed or tracked in a coherent manner, with ad hoc approaches taken by the ILs and the universities that house them. Drawing lessons from these experiences, USAID policy could evolve to address gaps in current law, regulation, and policy in order to address this situation and the unique nature of agricultural technology.

- ADS 318, which sets out USAID’s current policy on IP issues arising under USAID programs, is not sufficient to govern dissemination and management of agricultural IAs developed by ILs. The scope of ADS 318 and BDA is limited to certain types of IP such as patents (including plants), copyrights, and trademarks developed and subsequently protected by USG funding recipients. ILs do not, generally, seek IP protection of IAs they develop; therefore, most IAs do not clearly fall under the scope of ADS 318 and the BDA. ADS 318 also does not contain provisions tailored to the dissemination of agricultural IAs.

- Because ADS 318 is applied on a contractual and case-by-case basis, there is no uniformity in USAID policy on management of IP. It may be argued that such an approach provides flexibility in negotiating IP terms in a funding contract, but it is limited in scope since ADS 318 only covers certain types of IP.

- It is clear, however, that USAID has use rights to the IP generated under USAID projects, but this does not address challenges with management of agricultural IAs. It is also possible that USAID’s use rights could be compromised through the use of exclusive licenses, which may be preferred by the private sector in order to disseminate agricultural technology, whether protected by IP or not.

- Under regulation, USG’s rights are limited to a use right on the technology developed and protected by a funding recipient as a result of their activities under USG contracts, and these use rights are not always well defined. However, USG partners have the right to elect title if universities do not meet relevant requirements and restrictions (on invention disclosure, election of title, and filing and maintaining of patent applications) as set out under BDA and ADS 318. It is not clear, however, how USAID would pursue this right, nor does it appear to be necessary that USAID expand its rights beyond a use right.

- Gaps exist under the BDA and ADS 318 that are often filled by IL host universities, which have comprehensive university-wide IP policies. These university IP policies are not specific to ILs but apply more widely to IP generated by universities employees and contractors, including ILs.

- University policies are mostly tailored towards commercialization of IP, which effectively leaves out some of the important IAs developed by the ILs and overlooks the public good nature of agricultural technology.

- A focus on IP also emphasizes a certain type of technology and dissemination pathway (commercialization), largely overlooking other dissemination pathways, which will likely be more applicable for agricultural technology. This is an issue for USG and university policies.

- IL host universities own all IPR produced by the ILs. All of the rights associated with management, ownership, dissemination, and transfer of the technology vest in the IL host university. If a host university does not pursue protection of the technology, it can request that the funding agency allow the inventor to elect title to the IP. Even when IP protection is sought, dissemination to underrepresented stakeholders may still be a challenge, since commercial goals do not always align with broad distribution. This could be at least partially addressed through more specific USAID policy guidance on management of agricultural technology.

- University policies also differ across institutions, although they have to comply with the relevant federal laws. However, the gap in IP/IA policies related to federally funded agricultural technology has resulted in gaps in management of IAs produced by ILs.

Lessons Learned from IL Dissemination and Application to USAID Policy

- USAID thematic areas and phases of research (under the PIRS framework) provide a useful framework for tracking IL output; however, a more tailored approach to tracking ILs is warranted from a legal perspective. Many IAs developed by the ILs are in the form of social science research outputs, which take the form of knowledge products, including research reports, policy briefs, white papers, and peer-reviewed publications. Like other scholarly works, most of these knowledge products are governed by standard licensing agreements and publication contracts.

- USAID has increasingly stressed the need for open data and open access in their policies, and efforts are underway to enhance open access to peer-reviewed scholarly research resulting from federally-funded programs. This is in keeping with the requirement that all federally-funded research be publicly disseminated on an agency platform, such as USAID’s Development Data Library (DDL). This public access requirement specifically excludes trade secrets, commercial information, or other proprietary data.

- ILs and their partners have varied dissemination approaches. These depend upon the type of crop (e.g., hybrid, open pollinated or vegetatively propagated), market characteristics (market size and growth, willingness to pay), and potential scaling pathways, which will lead to different legal considerations and structures for technology dissemination.

- Some of these pathways focus more heavily on IPR and private sector engagement, while others are more community focused. Integrating dissemination considerations into IP/IA management would help ensure that agricultural technology reaches the desired market and that a social, public good component is integrated to help address gaps in technology dissemination and scaling.

- Sometimes, ILs and their partners will obtain IPR for developed technologies prior to transfer, as this enables them to trace how, where, and by whom the technology is used. IPR may also help attract greater interest from the private sector to scale and commercialize the technology. However, this is not the norm across ILs, which often transfer unprotected IAs rather than formally registered or claimed IPR due to the nature of the technology developed. Even when legal tools like licensing agreements are used to engage the private sector, these are not often based on IPR.

- Technologies that have higher potential for commercialization (commercial seed varieties, trademarkable storage products, vaccines, etc.) tend to generate more interest from the private sector, which takes a business-focused approach to dissemination and scaling. However, to protect their investment in branding and promotion, the private sector often seeks exclusive rights over technology, which can limit public access.

- Transfer of agricultural IAs through exclusive licenses can limit access of such technologies from intended beneficiaries like farmers and marginalized groups. Semi-exclusive/limited exclusive licenses could be considered instead, as they do not restrict the role of public actors such as NARES.

- Some IL partners, like NARES, play a critical role in technology dissemination. Engaging NARES in IA management (e.g., dissemination of improved seed varieties through licensing) can be invaluable for ensuring that technology reaches farmers and vulnerable communities. However, most NARES face particular resource challenges that limit their ability to claim and maintain IP and manage licensing programs due to staffing constraints and uncertainty over donor funding and government resource allocations. These constraints could be addressed at least in part through a policy approach to ensure that NARES are central to technology dissemination associated with federal funding, which may necessitate limitations on licenses with the private sector.

- For the CGIAR, another important IL partner, most assets are in the form of IAs and not formally claimed or registered IP. This is largely due to CGIAR policies and legal framework. As part of this framework, CGIAR Centers are not able to enter into purely exclusive licenses with the private sector and must put some limitations on these arrangements. CGIAR practices are evolving, as CGIAR Centers also contemplate how best to manage their IAs and make sure that they reach their intended beneficiaries. However, dissemination challenges and engagement with local partners likes NARES will still need to be addressed.

- ILs have noted knowledge gaps and financial challenges in dissemination of their technologies, which could be addressed by USAID.

Practices of Other USG Agencies, Donors, and International Partners

- Some USG agencies expand on BDA ownership provisions, such as in the case of contractor/employee-inventor title election, ownership rights modifications, waiver of title, or USG march-in rights, in order to align the BDA with the agency’s own policies on IP ownership and dissemination.

- The USDA IP policy also specifically addresses agricultural innovations, such as plant and seed varieties and animal vaccines, filling a gap under the BDA and other instruments which take a more limited view of covered technologies. Further, a Working Group on Competition and Intellectual Property was established by the USDA to discuss IP issues relating to seed variety development.

- Several agencies have in-house technology transfer offices, which may also deal with technology developed by external researchers who aid in the dissemination of federally-funded innovations, albeit primarily through commercial pathways. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has additional tools for in-house labs, including a Lab-to-Market initiative.

- USG policies on IP management and commercialization could be developed to include detailed guidelines for contractors to create their own plans for dissemination, subject to approval by the funding agency, which could take into account different dissemination pathways. Examples to draw upon include DOE’s guidelines for the creation of an IP management plan and NIST’s IP management overview, which provide guidance for contractors to strategically disseminate their research. These examples could be tailored to take into account the unique nature of agricultural technology and the findings relevant to ILs and their partners, particularly with respect to the importance of different dissemination pathways and partners.

- CGIAR Centers have adopted comprehensive monitoring and evaluation systems that could be looked to as good practices. For example, the CGIAR publishes an annual CGIAR IA Management Report pursuant to the CGIAR IA Principles. Some NARES, such as the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) and South Africa Agricultural Research Council (ARC), also do stocktaking on their IAs, particularly those that are protected or could be protected by IPR. If such stocktaking were integrated into USAID policy, it could be beneficial for tracking IAs developed under federal funding and assessing how commercial interests are pursued alongside public good dimensions.

- The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) has acknowledged that IP protection is sometimes needed to ensure broad access to technologies. If it furthers the foundation’s organizational goals, BMGF will require a non-exclusive, royalty-free license in the external background IP (humanitarian license). As long as it does not interfere with the scope of the humanitarian license, BMGF will also allow certain limited exclusive licenses. Although they are still developing their licensing policy, BMGF’s IP policy serves as a good model for USAID because it attempts to balance IP protection and commercialization with a global access strategy. It is important to note that there are some limitations on exclusive licenses, which is also in line with CGIAR practices.

Areas for Further Development and Study

- All of the findings and recommendations summarized above could form the basis for a comprehensive USAID Policy on Funded Agricultural Technology Management and Dissemination. A draft policy guide could be developed in annotated format, which could be used by other USG agencies as well and customized as appropriate. A new training module for agricultural innovation dissemination strategies could also be developed to add to the Federal Laboratory Consortium for Technology Transfer’s learning center. Legal tools could also be created to assist ILs and their partners.

- Some elements will require further investigation, including data rights and artificial intelligence where both law and practice are in flux and rapidly evolving. In particular, USAID should develop policies regarding the ownership, management, and accessibility of data inputs, datasets, and data tools by local partners. Even though USAID is not authorized to regulate AI, it could still develop best practice guidelines regarding AI ownership and management, including contingency plans for AI database monitoring. These will be particularly important to agricultural technology dissemination in the future and to striking a balance between innovation and the interests of underserved communities.

- USAID is uniquely positioned to bring together major donors and key partners to design and establish streamlined guidelines for managing public good IAs in agriculture. Such harmonization could reduce conflicts over legal frameworks for technology transfer and enhance local partners’ ability to disseminate agricultural technologies effectivity, ensuring that efforts align with practical needs on the ground and diverse donor policies.

- Although USAID currently uses the PIRS within the GFSS as a framework for tracking the development and progression of new or significantly improved technologies, practices and approaches, the current framework does not adequately address the complexities associated with managing IAs. USAID could explore ways to modify its MEL systems to also track the management and utilization of IAs for each innovation. This could help ILs better track IAs once they have transitioned to external partners ensuring that the innovations it supports are effectively managed and scaled.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and its Feed the Future initiative under the Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) has funded and supported agricultural research and development through twenty-one Innovation Labs (or ILs),1F1F[1] which have generated a range of innovative technologies. ILs are part of research investments made by USAID and draw on the expertise of U.S. universities and partner country research and academic institutions to develop, disseminate, and scale technologies to combat food insecurity and climate change.2F2F[2] The U.S. government (USG) also supports IL partners including CGIAR Centers, National Agricultural Research Centers (NARES), and private sector actors. ILs and their partners are part of the Feed the Future initiative’s focus on ending global hunger by cultivating new developments in agriculture, improving nutrition, and increasing food security.

ILs play an important role in bringing agricultural research to smallholder farmers and marginalized communities in Feed the Future countries. ILs generate many Intellectual Assets (IAs), some of which legally qualifies as Intellectual Property (IP), including crop varieties that improve food and nutritional security in low-income countries. IAs encompass any results or products of research and development activities of any nature whatsoever, including, but not limited to, knowledge, publications and other information products, databases, improved germplasm, technologies, inventions, know-how, processes, images, software, artificial intelligence systems, and distinctive signs, whether or not they are protected as IP. Most ILs do not seek intellectual property rights (IPR) for their technologies, although some ILs have sought IPR for technologies that have commercialization potential. The technologies developed by ILs, and their partners are transferred, disseminated, and scaled to promote their availability and accessibility by the intended users, namely farmers and consumers; however, these technologies are not reaching their targeted users at the desired rate.3F3F[3]

USAID does not have a clear policy in place to guide ILs and their partners on the management and dissemination of agricultural technology developed with USAID support and funding. The U.S. Government Global Food Security Strategy (GFSS) is the main guiding instrument on the pathway for agriculture-led economic growth, but it does not go into detail on management of IAs. The GFSS sees the uptake of technologies as a critical step to drive improved food security and nutrition and increased resilience, noting that agricultural research and development (R&D) are essential to meet the challenges of food insecurity, poor nutrition, environmental challenges, and biodiversity in a country.4F4F[4] These are key drivers of sustainable economic transformation.5F5F[5] Dissemination and scaling of agricultural technology is a major objective in GFSS projects, but this notoriously difficult task is often referred to as the “chasm” or the “valley of death,” as technologies developed in academic or other research institutions often fail to reach the market.6F6F[6] USAID policy guidance can be critical for striking a balance between encouraging innovation and ensuring that maximum benefit goes to underrepresented communities, smallholder farmers, and consumers in developing countries. The aim of this study is to highlight findings and recommendations that could contribute to a USAID guiding framework for maintaining incentives for further innovation by ILs and their partners while fostering broad access to technologies.

1.1. Unique Nature of Agricultural Technology

Many improvements in agricultural technologies are incremental and often build upon existing and publicly available technologies. For example, crop variety traits such as drought tolerance and disease resistance are often stacked on existing (and publicly available) varieties. Under these conditions, attribution of marginal contribution to the final product is often complicated. The incremental nature of agricultural innovations poses challenges for IP management. Traditional IP frameworks, which are designed for discrete, novel inventions, may not adequately capture the collaborative and cumulative nature of agricultural R&D. This distinction necessitates more flexible IP policies that can accommodate incremental innovations and ensure fair attribution and benefit-sharing.7F7F[7]

Agricultural innovations often need to be tailored to the specific agro-ecological conditions and the unique needs of local farmers and communities. This adaptation process is crucial for ensuring that the technologies are effective and sustainable in diverse environments. For example, a crop variety developed in one region may require modifications to thrive in another region’s climate, soil type, pests, and diseases. Local adaptation ensures that technologies are relevant and practical for end users, which is essential for widespread adoption and impact. To adapt technologies locally, extensive field testing and development are necessary. This involves conducting trials under local conditions to assess performance, identify potential issues, and refine the technology. Local research institutions, agricultural extension services, and farmer cooperatives often play a critical role in these testing and development efforts, providing the necessary expertise and resources.8F8F[8]

The agri-food system is highly dynamic, influenced by factors such as agro-ecology, market demands, and policy changes. This dynamism necessitates flexible and context-specific partnerships and legal frameworks. For example, as climate patterns shift, crops that were once suitable for a region may no longer thrive, requiring ongoing adaptation and support from research and extension services.9F9F[9] While standard IP policies have been effective in managing high-value patents in fields like engineering and biomedical sciences, the unique features of agricultural innovations call for a more tailored approach. This includes recognizing the public goods nature of many agricultural technologies, the incremental and cumulative nature of agricultural R&D, and the need for local adaptation and flexible partnerships.

1.2. Study Framework and Research Questions

The study began with an in-depth analysis of the policy, legal, and regulatory framework that currently applies to agricultural IAs produced by ILs. This included analysis of U.S. federal law, USAID’s policy on IPR, institutional policies of the host universities and relevant international law, all of which have an impact on IA management and dissemination. These are presented in Section 2.

The study also involved semi-structured interviews with key personnel from ILs, REFS, and other key stakeholders including U.S. Universities, CGIAR Centers, NARES, and other donors (See Annex 1 for list of key informants interviewed). To guide these discussions, the research team prepared questions on technology development, management, and dissemination by ILs and their partners, and each interview included the framing questions in Annex 2 and 3 along with more tailored questions that evolved over the course of the discussions. These interviews are referenced throughout the study and form the basis for some of the main findings and recommendations. The study was guided by the following interrelated evaluation questions:

- What legal considerations (including whether or in what form to claim IPR) govern or impact the development and dissemination of agricultural IAs developed under USAID projects?

- How is upstream management of IAs and IPR related to downstream scaling and transfer of technology?

- What are the different types of agricultural IAs produced by USAID-funded partners (including ILs), and how are these scaled and disseminated?

- What legal tools exist to facilitate (or hinder) the management and dissemination of agricultural IAs? How should these tools be designed with the unique nature of agriculture and the public good element of the IAs considered?

- What practices have been adopted by other USG agencies, implementing partners at universities, and partner institutions that could guide a USAID policy on management of agricultural IAs?

- How can IL partners and development stakeholders improve the dissemination of publicly funded IAs to support food security and agricultural development?

- How could a policy for management of agricultural IAs in Feed the Future crop improvement, research, and technology scaling programs enable achievement of Global Food Security Strategy Goals?

- What related issues would require further investigation?

As the focus of this study, the Feed the Future ILs under USAID’s REFS provide a uniquely suitable structure for examining the challenge of agricultural technology management and dissemination, due to their broad scope of crops, livestock, and policy areas, as well as their wide range of collaborating partners to foster greater scaling of investments in agricultural technology.

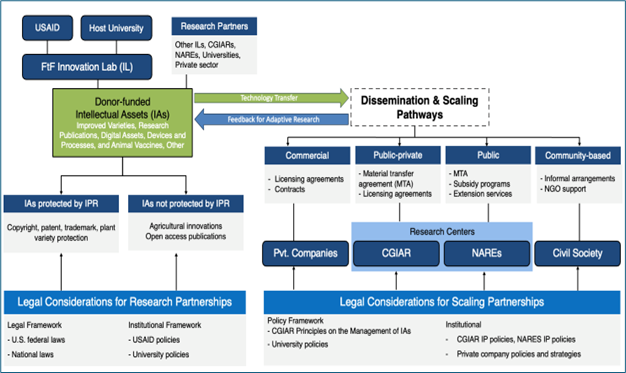

Examination of IL approaches to technology management and dissemination centered around different forms of IAs10F10F[10] developed by ILs, their scaling pathways, and different legal and institutional considerations based on these factors. These elements emphasize the need for adopting a flexible approach to IA management and also help inform recommendations for Feed the Future crop improvement, research, and technology scaling programs. These are summarized in Figure 1 below and elaborated upon in the sections that follow.

Figure 1: Intellectual Assets Developed by Innovation Labs, Dissemination and Scaling Pathways, and Legal Considerations

As illustrated in Figure 1, within USAID’s three clusters of Research and Development under Feed the Future – (1) plant and animal improvement research, (2) production systems research, and (3) social science research – the main research outputs or technologies produced by the ILs fall within five key categories: (1) improved varieties, (2) research publications, (3) digital assets, (4) novel devices and processes, and (5) animal vaccines. Some IAs could be legally protected as patents (including plant patents), copyrights, or trademarks. However, ILs do not typically pursue IP protection but have done so in instances where the IA has high commercial value. These IAs are disseminated and scaled along four main pathways: (1) commercial, (2) public, (3) public-private, and (4) community-based or civil society-based partnerships. Legal issues raise important considerations both regarding technology development and dissemination, and they inform tools for dissemination used by partners (e.g., licensing agreements).

In commercial pathways, private sector actors (such as manufacturers, wholesalers, distributors, or retailers) make technologies available to end users (such as smallholder farmers, processors, or consumers) through markets. Here, upstream policies could provide some guidance on the management of IP, but these are not generally tailored to agricultural IAs. Public sector dissemination and scaling pathways often use government programs, extension services, and agriculture input subsidy programs to produce and/or deliver an innovation to end users. Here, there is not much guidance from upstream policies, as there is little market incentive to protect the technology. Public-Private pathways leverage the strengths of both the public and private sectors to deliver innovations that meet public needs while ensuring efficiency, innovation, and sustainability. Here, policies of IL partner institutions such as CGIAR Centers and NARES are relevant. Community-based pathways depend on more informal channels and local groups such as civil society organizations, farmer organizations, or savings and loan groups to support the dissemination of technologies. Importantly, agricultural innovations tend to be considered “public goods,” which are further developed through public funding by international and national research partners (CGIAR Centers and NARES). The end users of most innovations from ILs are smallholder farmers who often lack willingness or ability to pay for royalties. This has particular implications for U.S. federal laws and USAID and university policies, which are examined in greater detail in the section below.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK GOVERNING INTELLECTUAL ASSETS DEVELOPED BY INNOVATIONS LABS

Understanding the management and dissemination of federally-funded agricultural technology must begin with the upstream legal and regulatory framework governing USAID and the universities that house the ILs. USAID’s current policy guidance on IP can be found under Automated Directives System (ADS) Chapter 318 (ADS 318), which provides guidance on the ownership of IP generated under the agency’s programs. This policy is integrated into individual agreements executed between USAID and its funding recipients. ADS 318 is based on the Bayh-Dole Act (BDA), which is a federal law governing the management of all technologies developed through funding from the USG. ADS 318 sets out rights and obligations of USAID, its funding recipients, and third parties in relation to IP developed under the agency’s programs. Although ILs partner with universities around the world,11F11F[11] each IL is hosted by a U.S. university that has individual IPR protection and dissemination policies which govern IL practices. ADS 318, U.S. federal laws and regulations, and host university policies govern management of IA/IP in upstream phases of research which can impact downstream dissemination and scaling of technology. They provide some insights but do not specifically deal with IP issues relating to agricultural technology or its dissemination. Further, ADS 318 and U.S. federal laws and regulations do not take into consideration IP policies of the U.S. host universities.

2.1. U.S Federal Laws

The legal framework surrounding IP management of federally-funded technologies can be assessed through two lenses: (i) U.S. federal laws and (ii) USG-specific regulations/policies that address specific issues relating to IP management. All USG agencies are bound to follow U.S. federal laws concerning IP management, the main one being the BDA and its implementing regulations.12F12F[12] The BDA governs all technology funded by USAID and other USG agencies. USAID has integrated provisions of the BDA and its implementing regulations into ADS 318.

The BDA and its implementing regulations guide USG policies related to inventions made by non-profit organizations. BDA provisions apply to federal contractors, which are defined as “small businesses and non-profit organizations”. Here, within the concept of “nonprofit,” universities are included, since both Section 401.14 of the CFR and the BDA (Sec. 201(i)) define a nonprofit organization as a “university or other institution of higher education.”13F13F[13] This means that the BDA also guides the policies of U.S. universities that host ILs.

According to the BDA, universities have the first option to decide whether to own, patent, and commercialize their inventions developed through federal financing support,14F14F[14] providing them with the option to “retain the entire right, title and interest throughout the world to each subject invention.”15F15F[15] This means that the BDA gives contractors16F16F[16] (or universities in the case of ILs) the first right to pursue ownership of technology created under federally-funded programs without having to forfeit that right to the federal government.

Ownership rights of contractors are subject to certain conditions. The contractor must provide USG a “nonexclusive, nontransferable, irrevocable, paid-up license to practice the invention or have the invention practiced throughout the world by or on behalf of the Government.”17F17F[17] The contractor must disclose any inventions to the relevant USG agency within two months of its internal disclosure and elect title within two years of the date in which the invention was disclosed to the agency.18F18F[18] The contractor must also file for patent application within one year of the date in which it decides to keep title over its inventions19F19F[19] and must periodically report on the utilization of the invention.20F20F[20]

Other restrictions on contractors include licensing obligations and payment of royalties to inventors. The BDA requires that nonprofit contractors share royalties with inventors and use the remaining balance for “scientific research or education.”21F21F[21] Many U.S. universities have interpreted this to mean that part of the royalties can go towards the development and protection of other inventions from the university’s community. Further, state universities must follow certain state law requirements on how to distribute royalties to their employees, including ILs. The USG is exempt from paying royalties to IP owners, because it retains a royalty-free license.22F22F[22] USAID policy elaborates that under a contract, royalties must not be excessive or inconsistent with the terms of the award. Further, a Contracting Officer may request information about royalty distribution.23F23F[23] According to FAR 31.205-37, which applies generally to USG contract provisions, royalties are allowable unless they are to be collected from the USG, which has a royalty-free license, or the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or expired.24F24F[24]

The BDA also gives agencies some options to control licensing and title under certain circumstances. A nonprofit contractor cannot assign rights in a federally funded invention without the permission of the agency, unless it is an entity that only manages inventions, such as a university research foundation.25F25F[25] There are also circumstances in which an agency may require licensing an invention to a third party if the head of an agency determines that it would be “necessary to achieve the practical application of the subject invention.”26F26F[26]

In addition to the above-mentioned use right provided to the USG, the BDA sets out instances under which the USG can restrict or modify the contractor’s rights. First, the federal agency (in this case USAID) could modify its funding agreement with the contractor in “exceptional circumstances” when the agency determines that restricting or eliminating the contractor’s right to retain title will better promote policy and objective of the BDA. USAID does not elaborate on what “exceptional circumstances” would be in this case, but other federal agencies like the Department of Energy (DOE) do (see Section 4). Here, USAID could provide further guidance in relation to restricting title to agricultural IAs. Second, the BDA provides that USG agencies may exercise march-in rights where the funding agency may require the contractor to provide a license to a third party if the agency determines that it meets four statutory conditions set out in the BDA.27F27F[27] This is a controversial provision, and the USG has never exercised march-in rights. Further, march-in rights are restrictive, as the contractor has a right of appeal.28F28F[28]

While the BDA covers scenarios under which a contractor seeks to transfer its own rights to a third party, USAID does not elaborate or interpret these provisions in its ADS. As a prerequisite, funding recipients have to ask the Federal government for permission to transfer such rights.29F29F[29] It is important to highlight that, within the context of the BDA, there have been some concerns about situations in which universities engage with private sector entities that aggregate patent rights for the sole purpose of enforcing patent protection.30F30F[30] In this situation, firms could hoard these patents and make money by suing any infringers, without properly applying or developing the actual invention. This would be contrary to the purpose of the BDA, which aims to promote the commercialization and application of federally funded inventions, as well as the intentions of USAID, which seeks to disseminate products for the public good.

Over the years, the BDA has succeeded in encouraging a significant increase in technology transfer through patents.31F31F[31] This is important for bringing certain technologies to the market and, ultimately, to end users who could benefit from them. One of the self-proclaimed benefits of the BDA is to allow for the licensing of federally-funded technologies to the private sector for further development or commercialization. An important goal of the legislation was to deliver technologies to end users through public-private partnerships.32F32F[32]

It is clear that the BDA has played an important role in boosting innovation; however, the BDA is mainly focused on certain forms of IP such as patents, which have limited application in the agricultural sector. Further, it has influenced universities to focus on commercial technologies that can generate revenue, as evinced in university policies (discussed below) and the move away from technologies that have a “public good” characteristic.

There are other federal laws of relevance. For example, the Federal Grant Cooperative Agreement Act (1977), provides guidelines on how government agencies should use their federal funds for assistance awards. For projects with universities, the Act mandates that the majority of the project administration must be performed by universities, which must meet certain requirements related to disclosing, reporting, and licensing inventions. With regard to USG agencies, they are limited to collecting and managing the information presented by the universities.33F33F[33] This limits USAID’s role in IP/IA generated through ILs. Another important law to consider is the Stevenson-Wydler Act (1980), which was the first major technology transfer law. This act was amended by the Federal Technology Transfer Act (FTTA) of 1986, which established cooperative research and development agreements (CRADAs).

U.S. federal legislation, particularly the BDA, is significant, because it sets a foundation for contractors’ (and universities’) claims to IP developed with federal funding. It does, however, have notable gaps, particularly with respect to its lack of detail and the scope of IP explicitly covered. Some of these gaps are addressed through other measures, including agency-specific regulations, although others are not.

2.2. USAID Regulations

In addition to the federal laws noted above, several U.S. agencies, including USAID and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC), both of which are Feed the Future partners, as well as the DOE, have their own regulations and approaches regarding IP management. Under current law and precedent, namely Auer deference, government agencies may clarify and interpret their regulations through policies and guidelines.34F34F[34] However, it is unclear whether recent Supreme Court decisions (Loper Bright and Relentless), which overruled Chevron deference, will also erode Auer deference in the future.35F35F[35] For now, it seems that U.S. agencies may continue to interpret their own regulations. USAID’s regulations and practices, along with those of select USG agencies, are particularly relevant to this study (see Section 4 for more detailed discussion of other USG agencies’ IP policies).

USAID’s framework on how to manage IP and its other operations is established in the ADS.36F36F[36] Chapter 318 provides guidance on IP rights and IP issues that may arise during the planning and implementation of agency programs and operations.37F37F[37] The ADS is specific to USAID and contains the agency’s operational policy and procedures for its programs. ADS 318 integrates several federal laws,38F38F[38] including the BDA and its implementing regulations39F39F[39] and closely follows BDA language.

ADS 318 has been applied to U.S. universities that receive federal funding, although there is no mention of universities in the policy. The ADS Glossary includes the term “Recipient” (of USAID funding), meaning “[a]n organization that receives direct financial assistance to carry out an assistance program on behalf of USAID, in accordance with the terms and conditions of the award and all applicable laws and regulations.”40F40F[40] The scope of the term “Recipient” is expanded upon under ADS 318 Model Marks Clauses, and includes “implementing parties under a USAID grant or cooperative agreement and any other persons or entities receiving assistance as well as their assignees, licensees, sub-awardees, and successors.” The above provisions could be interpreted to include partnering universities as recipients acting on behalf of their ILs, since it refers to implementing parties of grants or cooperative agreements. Likewise, the definition is broad enough to include “any other persons or entities receiving assistance,” which implies that ILs are also covered, as they are part of the covered universities. Finally, the definition refers to “assignees, licensees, sub-awardees and successors,” which might imply that ADS 318 also applies to third parties who are granted a license or right over the innovations developed under USAID´s funding.

Similar to the BDA, ADS 318 provides that the contractor (or the funding recipient) receives the right to seek title over the IP, but this is subject to certain restrictions. Per ADS 318, the USG receives a use right to IP developed and subsequently protected by contractors under USG programs in the form of a non-exclusive, non-transferrable, irrevocable, and paid-up license. Some guidance can be found in the U.S. Code on how USG agencies can exercise the use right conferred under ADS 318.

The use right is in relation to “subject inventions,” which are inventions “conceived or first reduced to practice in performance” of a contract or agreement.41F41F[41] BDA regulations provide some guidance on this, stating that if research activities, even if closely related, fall outside the scope of a USG funded project, prescribed USG rights do not apply.42F42F[42] An invention is not “conceived or first reduced to practice in performance” under a USG project if there is subsequent improvement of that invention using non-USG funds.43F43F[43] This means that USG use rights are restricted to inventions developed under a USG project, which could present a challenge for agricultural IA/IP that is incrementally developed with IL partners.

Title 15 of the U.S. Code states that “the government use license applies to inventions stemming from research partnerships with Federal Laboratories,44F44F[44] Federal employee inventions,45F45F[45] and federally funded inventions produced by contractors and grantees.46F46F[46] This includes inventions produced by ILs. It allows the government to use federally-funded inventions for its mission-driven purposes without a threat of legal challenges, especially for patent infringement.47F47F[47] The use license appears to apply to all USAID funding, regardless of funding level or co-development.

ADS 318 mainly provides guidance on three kinds of IP – patents, copyrights, and trademarks – extending its explicit scope a bit beyond the BDA but still remaining silent on certain forms of IP. In relation to patents, ADS 318 also specifically provides guidance for assistance awards to U.S. small businesses and non-profits (including universities). ADS 318.3.1.5, states the following:

Pursuant to 22 C.F.R. 226.36(b), assistance awards to U.S. small businesses and nonprofit firms should include 37 CFR 401.14. This provision allows the recipient to take title to subject inventions, subject to certain rights and restrictions, including providing the USG a non-exclusive, non-transferable, irrevocable, paid-up license to use, or authorize others to use, the subject invention throughout the world [emphasis added].

The inclusion of “certain rights and restrictions” means that USG assistance awards with universities must include clauses set out under 37 CFR 401.14, which provides a standard clause for the same use right to subject inventions as prescribed above with conditions on invention disclosure, election title, filing, and maintaining a patent right. This clause can be modified depending on the needs of the agency, as long as it is authorized under 37 CFR Part 401.48F48F[48] This provides that USAID can introduce alternative provisions in a contractor’s funding agreement in multiples instances,49F49F[49] including when USAID determines under exceptional circumstances that the restriction or elimination of right to retain title to invention will better promote a policy objective prescribed in the BDA. The agency has certain standards and obligations to meet when exercising these modifications, and the contractor has the right to appeal the use of exceptions. Further, AD 318.3.1.1 (Patent Rights – General) provides that the USG has the right to use the subject invention for USG purposes, including allowing USG partners to use the IP for USG programs. This limits USAID’s ability to guide dissemination and scaling of the technology.

ADS 318 also provides some guidance on copyrighted works. USG works can be copyrighted in other countries based on local laws and regulations.50F50F[50] Based on the type of data produced in copyrightable material, USAID rights in the data could be unlimited, limited, or restricted. Unlimited rights apply to data developed exclusively with USG funding. Here, USAID has the right to “use, disclose, reproduce, prepare derivative works, distribute copies to the public, and perform publicly and display publicly, in any manner and for any purpose, and to have or permit others to do so.”51F51F[51] USAID receives a paid-up, non-exclusive, irrevocable, worldwide license with unlimited data rights. USAID can reproduce and use the data within the USG but may not disclose or manufacture data to the public with permission of the contractor.52F52F[52]

USAID has certain rights in federally-funded data or software and can negotiate additional rights on a case-by-case basis. If copyrightable materials include a contractor’s proprietary information or product funded by non-USG sources, USAID must obtain additional rights before use.53F53F[53] These can include limited rights in previously acquired data or restricted rights in proprietary software. If a cooperative agreement contains a rights-in-data clause (FAR 52.227-14), which gives USAID an unlimited right in all data developed with USG funding, USAID will assume that it has an unlimited right in all data not marked as proprietary.54F54F[54] The rights-in-data clause also grants USAID a restricted right to computer software in the event the software was developed by a private enterprise and is financial, commercial, privileged, or copyrighted. USG cannot disclose this software outside the agency without prior permission of the contractor. USG can also reserve unlimited rights in copyrights for scientific and technical data using the rights-in-data clause. Though ADS 318 touches upon data rights of USG in copyrightable material developed under government contract, it does not expand on issues relating to protection of data, data privacy, ownership, or control of data which are becoming increasingly significant issues. Stakeholders consulted in the development of this study also raised concerns in relation to data collected. This is discussed further in Section 3.

ADS 318 provides some guidance on trademarks developed under USAID projects as well. However, this is mostly in relation to USAID’s option to obtain rights to trademarks developed under USAID projects to protect its own interests in the United States or other countries. Here, USAID could transfer the right to use the trademark to the partner to use it on USAID’s behalf. Issues such as trademark licensing have been highlighted by IL stakeholders as important to scaling of agricultural IAs; however, there is no support and guidance provided to ILs from USAID on this point. ADS 318 does, however, include a model clause that could be inserted into USAID assistance awards, which gives the USG a use right while holding the recipient responsible for use of license of the trademark by it and others.55F55F[55]

Important questions also arise downstream regarding USAID’s use right, particularly if the IA/IP developed under a federally-funded program is subject to an exclusive license that gives another party unfettered discretion regarding the use of an innovation. While this question is not addressed in ADS 318, it is important, particularly given the inclination universities and ILs to pursue commercial distribution channels, where exclusive licenses will be more commonly requested. Allowing any exclusive right over agricultural IA may make it difficult for USAID to maintain its use right unless the terms are designed to make it very clear which rights are implied for which parties. In addressing this question, USAID may find it helpful to look at the licensing policy of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), discussed in Section 4, and CGIAR’s approach to licensing. In both cases, limitations are placed on exclusivity in licensing, which could be beneficial for USAID to consider as well. These questions could be clarified in future USAID policy to avoid any possible conflicts.

While not mentioned in ADS 318, USAID funding recipients must fulfill the reporting requirements of the BDA through an online platform called iEdison, which is an interagency platform for BDA reporting hosted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Other USG funding recipients are also required to use this platform. The iEdison reporting requirement is mentioned in USAID’s supplement to the Federal Acquisition Regulations (AIDAR 752.227-70) and seems to be incorporated contractually. On this platform, contractors upload administrative information about subject inventions to iEdison, such as inventors, funding agency, brief descriptions, and public disclosure status, as well as title election and any patents filed.56F56F[56] This is different than the requirement that all federally funded research be publicly disseminated on an agency platform, such as USAID’s Development Data Library (DDL),57F57F[57] which exempts the public disclosure of “trade secrets, commercial information, materials necessary to be held confidential by a researcher until they are published, or similar information which is protected under law.”58F58F[58] In relation to Feed the Future activities, USAID has also built, in consultation with Feed the Future partner agencies, a “Framework Needed to Assess and Report on Feed the Future’s Performance,” which serves “to guide performance monitoring for the initiative.”59F59F[59]

2.3. Intellectual Property Management by IL Host Universities (Policies and Practice)

In line with the provisions of the BDA discussed above, many U.S. universities have technology transfer offices focused on IP management, which primarily manage patents and licensing activities. Over the past several decades, universities have become hubs for innovation, contributing significantly to sectors such as biotechnology, information technology, and engineering. In 2023, the National Academy of Inventors reported that the top U.S. universities collectively received thousands of utility patents, demonstrating their ongoing role in technological advancement and innovation.60F60F[60] Most high-value IAs (mostly patented) from universities come from a limited number of fields, such as engineering, biomedical sciences, computers and communication, and chemistry.

ILs do not have their own policies to manage the IAs they develop. Their IP management is based on the IP policies of the U.S. host universities that work as their management entity (the U.S. university is ultimately responsible for the conduct under the grant from USAID). Therefore, the IP policies of the universities that host the ILs are part of the legal foundation governing the relevant technology and its dissemination. These IP policies are university-wide and are not specific to the ILs. Like the BDA and ADS 318, most university IP policies focus on limited types of IP, primarily patents, and do not reference those that are common among agricultural technologies, such as plant breeders’ rights (PBR)/plant variety protection (PVP) or localized methodologies, which have particular considerations. In practice, university systems prioritize certain types of technologies, particularly those in the medical industry, over agricultural technologies. One notable exception includes the University of Georgia, which has an Integrated Cultivar Release System that works with Georgia agricultural state agencies, as well as the university’s research foundation and its College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, to provide IP protection, management, and marketing for plant breeding research and seed development.61F61F[61]

Host universities have the right to pursue ownership of technologies developed by the ILs. This right is conferred to universities under the BDA (which provides contractors the right to claim ownership over federally-funded technology) and ADS 318 (which implements the BDA through contractual arrangements). University policies provide further details on ownership of IP produced by university employees. University IP policies grant the relevant university both moral (e.g., claim of ownership) and economic rights (e.g., royalties) arising from inventions developed either (i) by individuals formally related to the university (either through employment, consulting or educational purposes) or (ii) through resources owned or procured by or through the university. How and whether each university seeks ownership over the relevant inventions seems to be determined on a case-by-case basis. The university, based on its own internal policies, may choose to apply for legal protection; however, this decision is often based largely on the commercialization potential of the technologies, as noted in their IP policies. This underlying priority of university IP policies does not fully consider the public good nature of agricultural technology or the full range of IAs developed by the ILs.

University policies can differ across institutions, and they exist independently of the USAID framework. However, universities policies have to comply with the federal laws set out above. Additionally, USAID policies are implemented through agreements with funding recipients (universities) which do explicitly reference the ADS. Like other funding recipients, universities also have reporting obligations. In some cases, university IP policies may provide additional guidance where the ADS is silent. For example, U.S. university policies provide for specific invention reporting requirements, while providing their own strategies for dissemination, often through commercialization.

The university policies surveyed include provisions on invention disclosure, ownership, commercialization and licensing, and revenue sharing. Some universities build in more specific procedures for dissemination and protection, while others have a generalized policy that seems to be designed for more flexibility.

Universities require their employees and faculty to disclose inventions to an IP unit or department, which then evaluates the invention for commercial potential. For example, Purdue University’s office of research will determine whether to pursue commercialization of inventions within 180 days, after which the university’s general counsel will determine the issue of ownership.62F62F[62] Michigan State’s technology office also considers commercial potential. If it does not decide to pursue a patent, ownership can be transferred to the inventor upon approval from a government sponsor (if using government funding).63F63F[63]

University IP units can sometimes be assigned ownership on behalf of the university and can also take steps to protect the IP. Universities usually use one of the following types of units to handle IP matters, including Bayh-Dole compliance: (i) centralized licensing office,64F64F[64] (ii) decentralized licensing office, (iii) foundation, or (iv) outside contractor.65F65F[65] Most commonly, among the universities surveyed, a university-affiliated non-profit, often called a “Research Foundation,” handles IP protection, compliance, reporting, and, in some cases, commercialization.66F66F[66] This organization or Research Foundation is assigned the IP generated by ILs and the university community more broadly. Other universities handle IP through a series of campus offices that report to a vice president or centralized provost office.67F67F[67] Sometimes an additional technology transfer office handles licensing.68F68F[68]

The BDA and university policies provide nuanced guidance on commercialization of federally funded research. The BDA speeds up the commercialization process as it allows universities to retain IP to the technology and commercialize it. The university has the right to own IP developed by ILs subject to the condition that it pursues protection of that IP in a timely manner and as per the conditions set out in the BDA. Based on this, many universities specify in their IP policy that the intent of ownership is not only to compensate for resources used but also to promote commercialization and development of R&D.

Many university policies allow universities to license the IP to a third party if it will benefit the public and the university. For example, Michigan State University’s licensing agreement generally includes a provision stating that the “licensee should diligently seek to bring the intellectual property into commercial use for the public good and to provide a reasonable return to the University.”69F69F[69] The university has the right to pursue royalties for any IP that is licensed by the universities. With a licensing agreement, the licensee receives a revocable right to commercialize the technology or creation they received. The licensing agreement includes the terms and conditions for both parties with respect to the long-term use and commercialization of a technology, including the period of time, extent of monetary compensation and royalties, and the need for record keeping.

If a university determines that a technology does not have commercial potential, it will usually defer ownership to the inventor. In such cases, university-sponsored scaling and dissemination are limited by the goal of monetization, leaving many ILs that do not produce IAs with commercial potential with little to no guidance. Stakeholders also noted that university policies could conflict with dissemination practices at the IL level, as ILs sometimes encourage ownership to be vested in local partners. Some IL stakeholders emphasized that the lack of incentive models at the university level to disseminate the technology is a significant issue. This could be because universities are concerned about liability or reputational risk associated with dissemination and scaling.

IL host universities provide a university wide framework for management and commercialization of IP, including those developed by ILs. These policies are based on the BDA and funding contracts that reference the ADS; however, they provide additional guidance on reporting requirements, commercialization, and management of IP. Universities decide whether IP protection should be pursued for an IA developed by the ILs. This decision is based on the commercialization potential of the IA, which is not a priority of the IL. In some cases, universities have assigned ownership of the IP to a third party so they can prioritize its management. University policies focus on limited types of IP, mostly patents, and do not prioritize management and protection of agricultural technology.

2.4. Key Findings and Gaps

The policies and guidelines for managing IAs under federally-funded projects and by U.S. universities have been largely developed with high-value patents in key fields in mind. Given that technologies developed by ILs are governed by the same technology transfer offices under standard university policies, it is worthwhile to explore whether these rules and policies are fit for purpose. Agricultural innovations have several key distinguishing features that merit a more nuanced approach from USAID and university partners. There are several gaps in current policies in context of agricultural IAs developed under USAID projects that are relevant to a potential USAID policy on IA management and dissemination.

- The U.S. legal and policy framework provides some guidance on management of IP developed under federal funds; however, it falls short of addressing challenges in relation to management of agricultural IAs created with federal grants and issues arising in the context of dissemination and scaling, which are often more important in agriculture than questions of how to protect a technology itself.

- The scope of ADS 318 and BDA, which focus on commercialization of innovations, applies to USAID funding recipients (universities), but it is not sufficient to guide dissemination and scaling of agricultural IAs. Its scope is limited to IP protection such as patent, trademarks, and copyright; however, most of agricultural technology transferred by ILs are unprotected and appear to be a bit outside of the scope of ADS 318 and BDA.

- IP/IA management of agricultural IAs developed by ILs is approached in an ad hoc and noncoherent manner. This is either based on university policy under which ILs exclusively develop IP or deferred to IL partners such as CGIAR Centers and NARES, which have their own institutional policies.

- Many issues regarding IPR of subject inventions seem to be addressed on a case-by-case basis during contract negotiations for funding. Although this gives some flexibility to contracting parties to negotiate IP terms in funding agreements, the scope is still limited to ADS 318, which only covers patents, trademarks, and copyright.

- The only clear position regarding IP management is that USAID can obtain or retain use right to share materials under the contract or grant for government use,70F70F[70] but this provision does not seem to be adequate to guide the dissemination of agricultural technology developed through USAID’s financial support.

- USAID has a use right to IP developed under USAID contracts; however, it can exercise advanced rights such as retaining title to a subject invention or assigning it to a third party if the funding recipient (the university in this case) does not meet certain obligations; however, it is unclear whether and how USG would do this. In fact, this may not be the most viable option, as exercising these rights has its challenges, and USG may have its own constraints in pursuing this option. As an alternative, USAID could require that its grantees/funding recipients meet additional requirements, such as reporting (including IA screening and IP capture, coordination and compliance requirements) in relation to management of agricultural IAs, so that it can pursue appropriate action.

- IL host universities have the first right to take title to IP developed with federal funding. These universities have their own priorities in pursuing IP, which may be based on commercial goals of the universities.