Abstract

The idea that country platforms can improve the effectiveness of development and climate action has gained increased traction in recent years, so has the idea that development and climate action must follow a systematic scaling approach to achieve transformational impact at scale. The purpose of this exploratory note is to bring these two ideas together to determine whether and how country platforms can support transformational scaling and whether and how a focus on scaling can make country platforms more effective. The note is exploratory and uses ChatGPT as a research aide along with references from the literature and examples from the Initiative on Mainstreaming Scaling in Funder Organizations undertaken by the Scaling Community of Practice (SCoP). The note aims to stimulate and provide a background for a discussion in the SCoP about how the concepts and practical application of country platforms and scaling complement each other and about how we can incorporate a focus on country platforms into our work in connection with the Campaign to Mainstream Scaling 2026-2030.

This paper concludes that country platforms are not a silver bullet. But neither is scaling. For country platforms and for scaling to succeed, the following conditions have to be met:

- Country platforms and scaling efforts both need to be transformational in design and implementation, not merely transactional.

- Transformational country platforms and scaling are intricately linked: the same factors determine their respective effectiveness.

- Transformational scaling must be an integral part of the design of country platforms and transformational scaling at country scale generally requires the establishment of a country platform.

- Country platforms and scaling involve complex interactions between a multiplicity of partners; this creates important tradeoffs in their design in terms of scope, inclusiveness, and costs.

- The effective functioning of country platforms and of scaling pathways requires that incentives and accountabilities among actors/stakeholders are aligned; very importantly, they also require that capacity, incentives and accountabilities within these organizations are aligned.

- Institutional infrastructure to support country platforms and scaling has to be developed and supported.

- The costs of country platform development and of scaling have to be transparently accounted for and funded.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE

A. Introduction

The idea that country platforms can improve the effectiveness of development and climate action has gained increased traction in recent years, so has the idea that development and climate action must follow a systematic scaling approach to achieve transformational impact at scale. The purpose of this note is to bring these two ideas together to determine whether and how country platforms can support transformational scaling and whether and how a focus on scaling can make country platforms more effective.

The note is exploratory and uses ChatGPT as a research aide (Annex 1) along with references from the literature (Annexes 2 and 3) and examples from the SCoP’s Initiative on Mainstreaming Scaling in Funder Organizations. Among the 28 case studies under this initiative two in particular represent examples of support for country platforms, the Global Financing Facility (GFF) and the Systematic Observations Financing Facility (SOFF).[1]

This note aims to stimulate and provide a background for a discussion in the Scaling Community of Practice (SCoP) about how the concepts and practical application of country platforms and scaling complement each other and about how we can incorporate a focus on country platforms into our work in connection with the Campaign to Mainstream Scaling 2026-2030.

The note first summarizes the ChatGPT responses to four key questions and then explores selected issues regarding the link between country platforms and scaling. It closes with a summary of takeaways.

B. How ChatGPT interprets the connection between country platforms and scaling

I chose to interrogate ChatGPT to help summarize the latest thinking on country platforms and scaling, to build on what already exists in the public realm and as a basis for defining the gaps in current thinking and analysis. As a first step I put the following four questions to ChatGPT:[2]

- How does a systematic approach to scaling support country platforms for development and climate action?

- How do country platforms for development and climate change action support transformational impact at scale?

- What are the limitations of country platforms for development and climate change action in supporting transformational impact at scale?

- How to align incentives in implementing country platforms for development and climate action?

The full answers are reported in Annex 1.

The answers offered by ChatGPT are comprehensive, well organized, and generally reflect the recent literature on country platforms and scaling. Table 1 represents a summary of key points.

Table 1: Summary of ChatGPT responses

| Definition of “Country Platform”: Country platforms are nationally-led coordination mechanisms designed to align public, private, and international stakeholders around a shared development or climate vision. They often involve: National governments (as conveners); donors, multilateral development banks; private sector and civil society; technical experts and communities.

Definition of “Systematic Approach to Scaling”? It refers to a deliberate, structured method to grow and replicate effective interventions or innovations in a way that: maintains or improves effectiveness; responds to local needs and contexts; ensures sustainability and inclusiveness. |

||

| How scaling supports country platforms | How do country platforms support transformational impact at scale? | Limitations of country platforms in supporting scaling? |

| 1. Aligns Scalable Solutions with National Priorities

2. Promotes Evidence-Based Decision-Making 3. Enables Coordination Among Diverse Stakeholders 4. Ensures Adaptability and Local Ownership 5. Improves Resource Mobilization and Efficiency 6. Strengthens Monitoring, Evaluation, and Accountability 7. Facilitates Innovation Transfer and Learning Conclusion: A systematic approach to scaling empowers country platforms to translate plans into action at scale, foster coherence across actors, and ensure that climate and development interventions are impactful, sustainable, and inclusive. It is not just about doing more—it’s about doing better, faster, and together. |

1. Aligning National Priorities with Global Goals

2. Coordinating Stakeholders and Reducing Fragmentation 3. Mobilizing and Blending Finance 4. Scaling Up Proven Solutions 5. Driving Policy and Regulatory Reform 6. Monitoring, Accountability, and Learning Conclusion: Country platforms enable transformational impact at scale by acting as integrated systems for aligning, financing, implementing, and scaling development and climate action. Their strength lies in national leadership, broad stakeholder engagement, and the capacity to mobilize resources toward inclusive, low-carbon, and climate-resilient growth. |

1. Weak National Ownership or Political Will

2. Fragmented or Inadequate Institutional Capacity 3. Financing Gaps and Unpredictable Support 4. Overly Complex or Bureaucratic Structures 5. Limited Focus on Local Inclusion and Equity 6. Misalignment Between Development and Climate Goals 7. Inadequate Monitoring, Learning, and Accountability 8. Vulnerability to Donor and Market Volatility 9. Lack of Flexibility for Transformational Change Conclusion: While country platforms offer a promising approach for scaling development and climate action, they are not a silver bullet. Addressing their limitations—through stronger national ownership, inclusive governance, sustained finance, and capacity building—is essential for realizing their transformational potential. |

| How to align incentives in implementing country platforms for development and climate action

ChatGPT highlights incentives for selected actors (Government, donors, private sector, MDBs and DFIs, CSOs and local communities); it also considers selected incentive instruments (results-based finance, performance contracts or compacts, tiered risk-sharing structures, data transparency platforms, joint governance boards). It also provides an implementation checklist:

|

||

Source: Annex 1

Table 1 does not represent the comprehensiveness and detail provided by the ChatGPT response. For that, the full text in Annex 1 needs to be consulted. It also contains ChatGPT’s references to specific country and regional examples of the application of country platforms.

C. Key issues in connecting country platforms and scaling

In this section I highlight and explore selected issues relevant to the links between country platforms and scaling. Most of these go beyond aspects and issues addressed in the ChatGPT response and in the country platform and scaling literature.

1. Country platforms need to be transformational, not just transactional.

In its recent work on mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations, the SCoP stressed the distinction between transactional and transformational scaling.[3]

- “Transactional scaling” refers to “doing more” with one-off interventions – more resources, larger projects, more co-financiers – and measures success in terms of the scale of funding and results achieved by a project’s or program’s end, with impact usually expressed against a baseline rather than relative to the size of the problem.

- “Transformational scaling” aims to deliver long-term sustainable impact at large scale beyond a project’s lifetime and emphasizes a viable business or funding model and adequate resources for ensuring ongoing delivery of goods and services over time, with one or more implementing organizations having the necessary mandate, capacity and reach to continue to implement at scale when external funders depart. Transformational scaling is usually accompanied by a significant effort at sustainable systems change to strengthen capacity, the policy enabling environment and, where appropriate, market systems. The success of transformational scaling is measured in terms of results and impact relative to the size of the problem (the denominator), not against the baseline.

By extension, we can also ask whether country platforms are transactional or transformational in design and implementation.[4] A transformational country platform will aim at long-term development or climate goals by addressing the problem(s) at a national scale and will measure success in terms of progress towards these targets. Individual programs and projects under the platform will be designed and implemented to contribute to pathways towards the long-term goals, rather than as one-off engagements with limited results measured against baseline. And participants in the platform will engage with a view to support transformational programs, form partnerships that stress effective cooperation or coordination and smooth handoff from one to another, and measure their contribution in terms of progress by the country towards long-term scale goals. Furthermore, transformational country platforms will focus on policy change and institution building not as one-off actions (such as adoption of a law or setting up of an institution) but as long-term and sustained efforts that focus on implementation of policies and institutional changes. Local ownership, sustainable and scalable business models, and effective long-term financing plans leading towards financial self-reliance are key aspect of a transformational country platform.

Transactional country platforms in contrast focus on short-to-medium term goals and measure progress against baseline. Projects and programs, partnerships, policy reform and institution building remain one-off, externally driven and not oriented towards self-reliance.

The country platforms supported by the GFF and SOFF are designed as transformational platforms as documented in the respective case studies. In the case of GFF, the support for country platforms in the area of maternal, child and adolescent health and nutrition is an explicit part of the design of this financing facility. In the case of SOFF, there is no reference to the concept of country platform, but de facto the design of the interventions at country-level in support of effective weather observations results in the development of a country platform for the support of a sustainable hydromet value chain.

2. Transformational country platforms require a focus on the same factors that are required for effective scaling.

The responses of ChatGPT demonstrate the close overlap between the success factors for country platforms and scaling: a long-term vision of sustainable impact at scale, evidence based and adaptive decision making in implementation, ownership of the agenda by national (local) stakeholders, creation of the necessary enabling conditions (esp. policies and institutions), effective partnerships, collaboration and/or coordination among key actors/participants, and transparent monitoring and evaluation during implementation.

3. Transformational country platforms and scaling are mutually supportive.

The responses of ChatGPT to the first two questions correctly highlight the mutual interdependency of transformational country platforms and scaling. For country platforms to be transformational they have to incorporate a long-term scaling perspective, where actors, programs and projects focus on appropriate pathways for sustainable impact at scale. In turn, country platforms are a helpful and often essential instrument for effective scaling by providing the organizational framework that allows all relevant actors to come together and seek to design and implement mutually aligned actions that support pathways towards sustainable impact at scale.

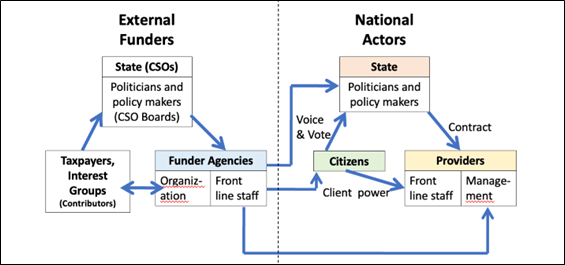

4. Transformational country platforms and scaling involve a complex alignment process.

Country platforms and scaling involve many actors who have to be coordinated for effective delivery on the country platform goals and on the scaling pathways in support of transformational impact at scale. Figure 1 is a simple, high-level representation of key actor groups involved and their potential interactions.[5] National actors include the state, service providers and citizens. The external actors are principally the international funders, public and private; they depend on their national governments (or philanthropic organizations) that in turn depend on the support of their tax payers and interest groups (or on their contributors in the case of philanthropic organizations). The relationships between actor groups are complex, involving direct, indirect and possible two-way linkages. Country platforms ideally need to encompass all relevant national stakeholders as well as external funders (official funders, international philanthropic organizations and private investors); these are shown in Figure 1 by the color shaded boxes. External funder agencies are accountable to their authorizing bodies (the governments or boards) and to their tax payers and other interest groups in their countries of origin, who therefore bear an indirect influence on country platforms and scaling.

Figure 1. Principal actor groups for country platforms and scaling

Source: Adapted from Linn (2012), which in turn was based on World Bank (2004)

Once one allows for the inevitable multiplicity of actors within each actor group, the challenge of achieving alignment becomes even more pronounced. Moreover, the number of actors and hence complexity will expand with the scope of the country platform and scaling pathway considered. Country platforms and scaling pathways that are sector or subsector specific, such as vertical funds, will involve fewer actors that need to be aligned than is the case for multisector or comprehensive national planning efforts.

But even vertical funds face alignment challenges: In the case of GFF, the alignment issue has been recognized as a central concern with a special committee set up including high-level representatives of national governments and of funder organizations. Its aim has been to find solutions that would facilitate sustained alignment of key actors around shared objectives. In the case of SOFF, the secretariat has to coordinate over 70 external partners, not counting the multiplicity of domestic partners in-country. Moreover, vertical funds and their country platforms and scaling efforts face pressures to broaden their scope due to inevitable linkages with other sectors (as has been the case for example with the Global Fund, which has been criticized for the distorting health sector impacts of its exclusive focus on a limited number of specific health threats).

Finally, within each organization one generally needs to distinguish between top management and front-line staff (as shown in Figure 1 for funder agencies and providers). While management sets the overall direction (e.g., supporting country platforms or scaling pathways), front-line staff are in charge of designing and implementing the specific activities in support of country platforms and scaling, but they often face conflicting demands on their limited time and resources as a result of “unfunded mandates.” This aspect has not been recognized sufficiently in the case of the country platform literature, but has been one of the central findings of the SCoP’s Initiative on Mainstreaming Scaling in Funder Organizations. We will return to this important aspect when considering next the issue of incentives and accountability.[6]

5. Incentives and accountability are central to transformational country platforms and scaling

A key factor helping the multiple actors align with a common strategy under a country platform or scaling initiative are the incentives that they operate under. The important role of incentives and accountability in ensuring effective scaling has been recognized for scaling, but apparently less so for country platforms. For scaling, Linn (2013) applied the framework in Figure 1 to focus on the incentives for national actors and for external actors, with the main incentive/accountability challenges and instrumentalities for addressing them summarized in Table 2 and 3 respectively (next page).

For country platforms, it is notable that when asked about the limitations of county platforms, ChatGPT does not explicitly list challenges of incentives and accountability (see Annex 1). This indicates that so far the incentive/accountability issue has been given little attention in the country platform literature. Only when asked specifically about how to align incentives for country platforms does ChatGPT provide a detailed answer considering separately the potential incentives for governments, donors, private actors, MDBs and civil society/local communities, along with ways to align incentives for each of these groups. It also lists a limited number of mechanisms that are helpful in aligning incentives: results-based finance (RBF), performance contracts or compacts, tiered risk-sharing structures, data transparency platforms, and joint governance boards. The literature on Country Platforms listed in Annex 2 generally does not address incentive and accountability challenges or, where it does, does so very superficially.

Table 2. National incentive/accountability challenges and instruments to address them

| Incentive/accountability challenges | Instruments to address these challenges |

|

|

Source: Adapted from Linn (2013)

Table 3. External funder incentive/accountability challenges and instruments to address them

| Incentive/accountability challenges | Instruments to address these challenges |

|

|

Source: Adapted from Linn (2013)

ChatGPT and the scaling literature, while offering limited insights and guidance on inter-agency incentive/accountability issues, have nothing to say on intra-organizational incentives and accountability. The SCoP’s work on institutionalizing scaling in government organizations[7] and its Initiative on mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations[8] are an exception. For funders in particular, the SCoP mainstreaming work stresses the need for front-line staff and middle management to have clear scaling capacity, incentives and accountability based on

- mission and vision statements that focus on transformational results at scale;

- operational policy guidance and scaling tools; on budget resources for analysis, partnership building and coordination;

- the availability of financial instruments for support of scaling;

- scaling skills acquisition and performance incentives; and

- learning and accountability through monitoring and evaluation systems that incorporate scaling explicitly.

The 27 case studies of funder scaling practices carried out under the SCoP’s mainstreaming initiative demonstrates that very few funders so far have addressed the challenge of creating internal incentives and accountabilities (and the related capacity needs) for effective mainstreaming of scaling in their organizations. It stands to reason that they also have limited capacity, incentives and accountability to support transformational country platforms.

The GFF and SOFF represent exceptions to this experience: The GFF has a well-developed approach to creating incentives for scaling and country platforms. The grants which GFF provides to countries have been used to support the development of long-term visions and investment plans based on in-depth health sector analyses, the creation of broadly inclusive country platforms with a policy reform and institution building agenda, financing plans, transparent data collection and intensive monitoring and evaluation focused on the long-term transformational results agenda. It also addressed some of the intra-organizational incentive issues in the World Bank by grant-cofinancing for World Bank projects[9] and in this connection offering additional budget resources for World Bank project staff for analysis, country dialogue and coordination.

However, despite this availability of incentives, the GFF has encountered persistent difficulties with ensuring the alignment of national and external actors in the health sector around country-owned strategies, including that of World Bank country teams. One explanation for this experience is that the incentives which the GFF has been able to offer have not been large enough to offset the disincentives embedded in current national political and bureaucratic structures and in World Bank operational practices. In the case of other external (non-World Bank) funders, GFF does not offer any outright incentives in a context where the internal incentives for these other funder organizations generally militate against effective alignment with country platform and scaling pathways.

SOFF also has a well-articulated incentive structure for its national partner organizations, for implementing partners and for technical peer advisers (results-based grant funding for meteorological organizations, and cost reimbursement for implementing entities and peer advisors). During its first three years of existence these incentives appear to have worked well, but it remains to be seen whether that experience will last over the long haul. For the moment, the main constraint is the lack of sufficient funding for SOFF itself which has meant that it has not been able to meet the demand from countries ready to invest in improved weather and climate observation capacity.

6. Country platforms and scaling need an institutional infrastructure

Country platforms and scaling pathways need an institutional infrastructure to support their effective functioning. In the case of the country platforms a secretariat has to be established (either with an existing organization or newly created). The secretariat serves as a convening and coordinating body, supports the development of an inclusive consultation process, formulates a country strategy, creates a transparent information base, and monitors and evaluates implementation. In the case of scaling pathways, an intermediary function is generally required to support the development of an inclusive vision of transformational impact at scale, provide analysis, information, finance and incentives for the various partners to join forces, support the policy and institutional changes required, and support monitoring and evaluation.

In the case of GFF and SOFF, the secretariats of these multilateral facilities have acted as key external supporters of country platforms and served as scaling intermediaries, bringing together and incentivizing national and international actors and partners to pursue sustainable impact at scale at country level. In the longer term, however, it is critical that the secretariats’ intermediating functions are taken over fully by national, rather than external organizations.

7. The costs of country platforms and scaling need to be transparently accounted for and funded

One of the key findings of the SCoP’s initiative on Mainstreaming Scaling in Funder Organizations is that effective scaling involves costs and requires dedicated resources and funding. The costs include the time, institutional and financial resources necessary to develop and sustain ownership, to build consensus and partnerships that support scaling pathways at country level, and to finance the intermediary function, the required incentives, and the analytical, monitoring and evaluation work that are needed. The same is true for country platforms. The costs of their institutional infrastructure and required incentives need to be accounted for and funded. We found that the prevalence of “unfunded” mandates has been a major constraint to mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations and they will likely also constrain country platforms.

In the case of GFF and SOFF a limited number of international funders have financed the establishment and functioning of these two organizations, covering their organizational costs and financing (some of) the analytical, investment and incentive requirements for effective country platform development and program delivery. In both cases, their limited financial resources have imposed constraints on the effectiveness of their support for country platforms and scaling.

D. Implications for the development of country platforms and scaling efforts

Increasing effectiveness of international development action has long been the goal of many international forums, conferences and agreements, including the High-Level Forums on Aid Effectiveness in Rome, Paris, Accra and Busan and the recurrent Financing for Development conferences organized by ECOSOC. Among the principal stated goals are ownership, alignment, harmonization, managing for results, and mutual accountability. However, in practice there has been little progress at country level in achieving these objectives and in particular achieving the coordination, cooperation and alignment required for transformational and sustainable development impact at scale.

Country platforms and scaling are among the most recent entrants in the efforts to improve development effectiveness. Country platforms are not a silver bullet, as noted by ChatGPT (see Table 1). But neither is scaling. For country platforms and for scaling to succeed, the conditions summarized in the following bullets have to be met; the preceding analysis provides the justification for each bullet:

- Country platforms and scaling efforts both need to be transformational in design and implementation, not merely transactional.

- Transformational country platforms and scaling are intricately linked: the same factors determine their respective effectiveness.

- Transformational scaling must be an integral part of the design of country platforms and transformational scaling at country scale generally requires the establishment of a country platform.

- Country platforms and scaling involve complex interactions between a multiplicity of partners; this creates important tradeoffs in their design in terms of scope, inclusiveness, and costs.

- The effective functioning of country platforms and of scaling pathways requires that incentives and accountabilities among actors/stakeholders are aligned; very importantly, they also require that capacity, incentives and accountabilities within these organizations are aligned.

- Institutional infrastructure to support country platforms and scaling has to be developed and supported.

- The costs of country platform development and of scaling have to be transparently accounted for and funded.

As part of the Scaling Campaign 2026-2030, the SCoP has identified a possible initiative on country platforms and scaling as follows:

“Country Platforms As a Locus for Country Scaling. This would examine the shifts in leadership, ownership, governance and incentives needed to maximize the value of country platforms as Transformational Country Platforms so they can serve as a foundation for achieving sustainable outcomes at scale. What are examples of where such efforts have been successful at getting traction around scaling? Pros and cons of single- vs multi-sectoral platforms? Implications for sustainable scaling of who convenes and participates in these platforms, how they are governed, staffed, and resourced? What are typical challenges? What is needed to test and learn from more effective use of transformational country platforms in the future?

The conclusions of the exploratory analysis in this note confirms that country platforms and scaling are intricately related and mutually supportive and highlights specific aspects of these linkages that deserve further exploration as part of the Campaign. But the main takeaway so far is this: without an explicit focus on transformational scaling by all major actors involved, country platforms will not achieve long-term development impact at a national scale in their areas of engagement.

Annex 1. Country Platforms and Scaling: Answers by ChatGPT

A. How does a systematic approach to scaling support country platforms for development and climate action?

ChatGPT said:

A systematic approach to scaling plays a crucial role in supporting country platforms for development and climate action by providing a structured, coherent, and adaptable framework for implementation, coordination, and long-term impact. Here's how this approach adds value: What Is a "Systematic Approach to Scaling"? It refers to a deliberate, structured method to grow and replicate effective interventions or innovations in a way that:

What Are "Country Platforms"? Country platforms are nationally-led coordination mechanisms designed to align public, private, and international stakeholders around a shared development or climate vision. They often involve:

They aim to:

How a Systematic Approach to Scaling Supports Country Platforms 1. Aligns Scalable Solutions with National Priorities

2. Promotes Evidence-Based Decision-Making

3. Enables Coordination Among Diverse Stakeholders

4. Ensures Adaptability and Local Ownership

5. Improves Resource Mobilization and Efficiency

6. Strengthens Monitoring, Evaluation, and Accountability

7. Facilitates Innovation Transfer and Learning

Real-world Examples

Conclusion A systematic approach to scaling empowers country platforms to translate plans into action at scale, foster coherence across actors, and ensure that climate and development interventions are impactful, sustainable, and inclusive. It is not just about doing more—it's about doing better, faster, and together. |

B. How do country platforms for development and climate change action support transformational impact at scale?

ChatGPT said:

Country platforms for development and climate change action are strategic frameworks that align national priorities with international support to drive transformational impact at scale. They serve as coordination hubs that integrate funding, policy, and technical assistance, bringing together government, private sector, development partners, and civil society to achieve shared goals. Here's how they support large-scale transformational change: 1. Aligning National Priorities with Global Goals Country platforms ensure that domestic development and climate objectives (e.g., NDCs, NAPs, SDGs) are at the center of planning and investment efforts. This alignment:

2. Coordinating Stakeholders and Reducing Fragmentation They act as convening mechanisms that bring together:

This coordination prevents duplication, ensures resource efficiency, and increases impact by integrating efforts under a unified national platform. 3. Mobilizing and Blending Finance Transformational change requires significant funding. Country platforms help:

4. Scaling Up Proven Solutions By identifying and replicating successful pilots or innovations, country platforms enable:

5. Driving Policy and Regulatory Reform They provide a structured approach for:

6. Monitoring, Accountability, and Learning Country platforms typically include M&E mechanisms that:

Examples in Practice

Conclusion Country platforms enable transformational impact at scale by acting as integrated systems for aligning, financing, implementing, and scaling development and climate action. Their strength lies in national leadership, broad stakeholder engagement, and the capacity to mobilize resources toward inclusive, low-carbon, and climate-resilient growth. |

C. What are the limitations of country platforms for development and climate change action in supporting transformational impact at scale?

ChatGPT said:

Country platforms offer a powerful model for aligning national development and climate goals with international support, but they also face several critical limitations that can constrain their ability to deliver transformational impact at scale. Here are the key limitations: 1. Weak National Ownership or Political Will

2. Fragmented or Inadequate Institutional Capacity

3. Financing Gaps and Unpredictable Support

4. Overly Complex or Bureaucratic Structures

5. Limited Focus on Local Inclusion and Equity

6. Misalignment Between Development and Climate Goals

7. Inadequate Monitoring, Learning, and Accountability

8. Vulnerability to Donor and Market Volatility

9. Lack of Flexibility for Transformational Change

Conclusion While country platforms offer a promising approach for scaling development and climate action, they are not a silver bullet. Addressing their limitations—through stronger national ownership, inclusive governance, sustained finance, and capacity building—is essential for realizing their transformational potential. |

D. How to align incentives in implementing country platforms for development and climate action?

ChatGPT said:

Aligning incentives in implementing country platforms for development and climate action is essential for ensuring cooperation, accountability, and long-term impact among diverse stakeholders—including governments, international donors, private investors, and civil society. Here's a structured breakdown of how to align incentives effectively: What Are Country Platforms Country platforms are nationally-led coordination mechanisms designed to align finance, policy, and implementation across stakeholders for development or climate goals. They act as a central hub for aligning public, private, and international resources with national priorities. Key Principles for Incentive Alignment 1. Government Ownership with Clear Accountability

2. Donor Coordination and Predictability

3. Private Sector Participation

4. Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and DFIs

5. Civil Society and Local Communities

Mechanisms to Align Incentives

Case Study Examples

Implementation Checklist

|

E. What are some successful country platforms other than for climate action?

ChatGPT said:

Country platforms have been used successfully beyond climate action in various development contexts—such as health, education, agriculture, and post-conflict reconstruction—often to coordinate aid, align national strategies, and mobilize resources at scale. Below are some notable examples: 1. International Health Partnership (IHP+) / UHC2030 Platforms – Health Sector

2. New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition – Agriculture

3. Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) – Post-Conflict Recovery

4. General Budget Support Platforms – Economic Governance

5. Compact with Africa (G20 Initiative) – Investment and Reform

6. Local Education Groups (LEGs) under Global Partnership for Education (GPE)

Key Takeaways Successful non-climate country platforms typically share these features:

They work best when platforms are embedded in national systems, inclusive, and flexible enough to adapt to changing needs. |

F. Comparison between non-climate and climate-focused country platforms

Here's a comparison table between non-climate and climate-focused country platforms, showing similarities and differences in their purpose, design, success factors, and limitations: Country Platform Comparison: Climate vs. Non-Climate

Key Differences

Convergence Trends Many non-climate platforms are integrating climate resilience, especially in sectors like:

Conversely, climate platforms increasingly focus on co-benefits like job creation, equity, and health—blurring the lines between development and climate outcomes. |