Abstract

Development effectiveness by governments and development funders requires that their actions result in sustainable impact at scale, i.e., that they address identified development problems to a significant and measurable extent and on a sustained basis. In most cases, sustainable impact at scale cannot be achieved over short time horizons or spontaneously. It requires deliberate, systematic, and sustained action by public and private agencies, supported by third-party funders, in pursuit of a trajectory of action (“scaling pathway”) that takes a specific intervention or a set of policy or institutional reforms as the starting point and eventually leads to sustainable impact at scale.

This paper draws on the growing scaling literature and practice and on the work of the Scaling Community of Practice over the decade of its existence. It presents a framework primarily for public sector-driven scaling by looking at scaling through three different lenses: (i) the scaling pathway from innovation to sustainable impact at scale; (ii) the relationship between scaling and system change in the pursuit of sustainable impact at scale; and (iii) implications for the prevailing project-based approaches. The paper then consolidates these three perspectives in a holistic approach to scaling that incorporates relevant aspects of systems change and the dynamics of operating in a project world. The paper concludes with a set of core questions for practitioners.

This paper is an updated version of the Scaling Fundamentals paper originally published in May 2024.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Richard Kohl and Ben Kumpf for their encouragement and for their comments on a draft of this paper. All views expressed are solely those of the authors. The authors also are indebted to Laura Ghiron and Ruth Simmons for their scaling wisdom and unstinting support over the last twenty years. Their development of the ExpandNet scaling approach and tools for practitioners contributed greatly to our understanding of the fundamentals of scaling.

Introduction

Development effectiveness by governments and development funders requires that their actions result in sustainable impact at scale, i.e., that they address identified development problems to a significant and measurable extent and on a sustained basis. In most cases, sustainable impact at scale cannot be achieved over short time horizons or spontaneously. It requires deliberate, systematic, and sustained action by public and private agencies, supported by third-party funders, in pursuit of a trajectory of action (“scaling pathway”) that takes a specific intervention or a set of policy or institutional reforms as the starting point and eventually leads to sustainable impact at scale.

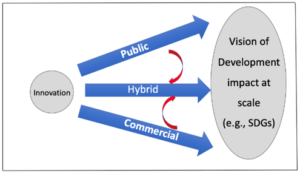

As illustrated in Figure 1, scaling strategies can be usefully categorized into those that rely principally on public sector action (e.g., education), those that rely on market-based private action (e.g., agriculture, cell phone services), and hybrid strategies in which public and private action are closely intertwined (e.g., health services). Since public policy and regulation affect commercial action, and since public service provision generally involves some degree of private engagement (e.g., contractors supplying inputs), in effect most pathways are hybrid in nature. Nonetheless, we find it useful to consider which is the principal driver of scaling – public or private action — since the enabling factors will differ significantly across the different types of pathways.

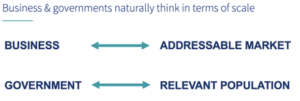

The simplest route to scale is commercial scaling where the profit motive provides both the impetus and the funding needed for sustainable scaling. National and local governments likewise have a mandate to think and plan at scale and possess an infrastructure for provision of goods and services over time, though often without the luxury of a self-generated source of funds. (Figure 2, panel A)

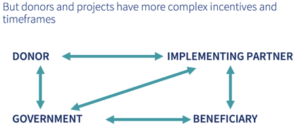

In contrast to these direct routes to scale, most donor funded efforts have complex incentives and accountability mechanisms that privilege time-bound projects and depend on more complex scaling strategies. (Figure 2, panel B)

Figure 2: Simple and complex pathways to scale

Panel A

Panel B

Source: Authors

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition among development and climate leaders that the prevailing project-based, donor-funded model is broken. Importantly, the “science of scaling” has also evolved from its initial linear focus on expanding single (often imported) interventions towards approaches that incorporate attention to the systemic changes needed to achieve sustainable impact at scale; that assess early on the scalability of innovations and interventions; that explore the roles and incentives of different actors – innovators, implementers, intermediaries and funders – in the scaling process; and that recognize the challenges, tradeoffs, and risks that need to be addressed in pursuing a scaling agenda. That recognition has been informed by, and has contributed to, an expanding array of case-based experience focused on improving and systematizing the scaling strategies, policies, and practices used by funders, government officials, and program implementors; and it is reflected in the new development narrative voiced by the leaders of many of those institutions. Although mainstream practices continue to lag, pressure for change is building, and the pace of strategic and operational reform is quickening.

This paper draws on the growing scaling literature and practice and on the work of the Scaling Community of Practice over the decade of its existence. It presents a framework primarily for public sector-driven and donor-supported scaling by looking at scaling through three different lenses: (i) the scaling pathway from innovation to sustainable impact at scale; (ii) the relationship between scaling and system change in the pursuit of sustainable impact at scale; and (iii) implications for the prevailing project-based approaches. The paper then consolidates these three perspectives in a more comprehensive approach to scaling that incorporates relevant aspects of systems change and the dynamics of operating in a project world. The paper concludes with a set of core questions for practitioners.

Getting from innovation to impact at scale

One way of looking at scaling is to start with a well-defined development problem or vision of desired development impact and match it with innovative solutions that shows promising results in addressing the problem. The vision of impact at scale could, for example, be a Sustainable Development Goal (or target) or a target for CO2 emissions established by the Paris Agreement on climate change; or it could be a particular national or municipal health, education or infrastructure outcome. The question then becomes how to bring one or more solutions to a scale that address the problem to a significant and measurable extent and on a sustained basis – the scaling process and pathway.

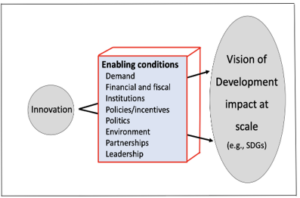

Scaling operates within an ecosystem of enabling – or constraining – conditions (Figure 3) that become increasingly relevant as coverage and institutionalization progress. These conditions include demand for the good or service which the innovation offers; the financial and fiscal resources needed to bring the innovation to scale; the institutional capacity to plan, organize and implement the innovation at scale; policies and the incentives for action; political support for or opposition against the intervention or scaling process; environmental and natural resource constraints; potential partners for implementing the pathway; and leadership driving the scaling process forward. Paired with the inherent characteristics of the intervention itself, contextual factors shape the feasibility of scaling and preview the challenges a scaling strategy will have to overcome. Later in this document we discuss in some detail this complex relationship between scaling, the ecosystem of constraining and limiting conditions, and systems change.

Mexico’s conditional cash transfer program “Progresa-Oportunidades,” a government program widely acknowledged as demonstrating great development effectiveness, is an example of a successful effort to achieve sustainable impact at scale with a well-designed scaling pathway as briefly summarized in Box 1. The way the program addressed the enabling and constraining conditions facing it is described in Box 2.

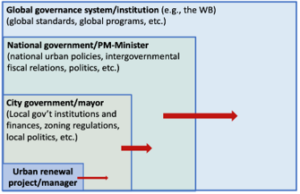

figure 4

In the public sector, the appropriate vision or aspiration for scale depends on where a given actor sits within the system. For example, for a manager of an innovative housing initiative in an urban neighborhood, the appropriate scale might be impact on improving housing in the neighborhood; for a mayor of a city, it might be improvement of housing conditions at the scale of her or his city; for the prime minister of a country, it might be meeting the housing needs in her or his country; and for global actors, such as the head of a large UN agency or of the World Bank, the vision of scale should be to address housing needs globally. (See Figure 4.) However, for each of these types of actors, it is worth considering whether and how an innovative initiative that is shown to work at a particular scale (community, city, national) could be replicated or leveraged beyond the immediate boundaries of the setting and target group on which it initially focused (reflected in the red arrows in Figure 4). This implies, for example, that the project manager (and funder) of a community-based housing project might consider during planning, implementation, and evaluation whether and how to support and lay the foundation for replication in other communities. In the same vein, a mayor might consider what is needed to introduce similar solutions not only in his or her city, but in other cities, say through the conference of mayors. And for a national government, sharing and extending its experience with other countries is at the heart of South-South Cooperation. More generally, it means that while actors at local levels can generally not be expected to pursue national or global-scale goals on their own, more attention could be given to creating institutions and mechanisms that ensure that local (or national) innovations are identified for possible scaling nationally (or globally). We return to this need for intermediation later in this section.

Another useful way of categorizing scaling pathways revolves around the intended role to be played at scale by the organization that originated and piloted the intervention (see Table 1). In Expansion strategies, the originating organization grows to meet the need or demand. In Replication strategies, the originating organization transfers implementation and funding responsibilities to one or more other organizations, typically the government or the private sector. And in Collaboration strategies, the originating organization continues to be involved over time in selected elements of implementation, such as quality control or training of trainers, but does so alongside other organizations that take on significant responsibilities.

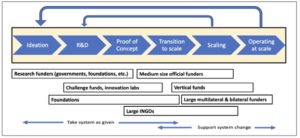

The scaling journey for an innovation can be broken down into six stages: (i) ideation, (ii) research and development, (iii) proof of concept, (iv) transition to scale, (v) scaling, and, finally, (vi) operating at scale (Figure 5). Monitoring and evaluation are critical for adaptive management all along the scaling pathway, not only to understand whether the desired impact is achieved but also how the enabling conditions are supporting or constraining the scaling process, and whether the design of the innovation or the scaling strategy may have to be changed accordingly. For this reason, while the stages are typically sequential, there are important feedback loops (indicated in stylized fashion by the reverse arrows in Figure 5), where, during the later stages (especially for “Scaling” and “Operating at Scale”), evidence gathered during implementation of the scaling process results in new ideas that may lead to adaptation of the intervention or the scaling strategy. This is the essence of good adaptive management. Box 3 summarizes the scaling pathway of the Progresa-Oportunidades program as an illustrative example.

Figure 5: The role of funders in the six stages of scaling

Source: Adapted from IDIA (2017)

As interventions pass through the six stages of scaling, the nature of the scaling process will likely change in various ways, including the following:

-

- Systemic enabling conditions: As indicated by the horizontal blue arrows in Figure 5, in the early stages of an innovation, systemic factors will have to be taken largely as given since the scope of the innovator or innovating organization is too limited to influence the system. However, change makers who wish to see interventions ultimately adopted widely should consider the feasibility of modifying or adapting to these systemic constraints over time. (For more on systems change, see Section 3 below.)

- Types of scaling: As noted above, scaling pathways can be of three broad types: expansion, replication, or collaboration, differentiated by the role eventually played by the organization that originated and pilot tested the intervention. Over the scaling pathway, the type of scaling may shift, with expansion options more likely to be relevant in the early stages of innovation and transition to scale, while replication options will more likely be relevant for the middle and later stages. Collaboration options (partnerships and alliances, networks, and coalitions) can be helpful throughout. (See Figure 5)

- Transition from scaling to operating sustainably at scale: A key transition that is often neglected is the transition from scaling to operating sustainably at scale. In addition to expanded coverage, the latter involves provision for all the costs and activities associated with operating and maintaining the assets and capacity to support delivery at scale and in perpetuity. Because these actions and expenses are generally seen as mundane and politically less attractive, and because they typically involve significant organizational challenges, they tend to be neglected.

- Actors – Researchers, innovators, implementers, intermediaries: Actors and their roles typically change over the course of a scaling journey. For example, researchers and innovators typically are focused on developing and testing ideas, but generally do not have the capacity or interest in developing or seeing through a scaling process. Implementers therefore have to take over at some point along the scaling pathway, supported as appropriate by intermediaries that assist the scaling process in a variety of ways including strategic planning, partnership development, financial mobilization, and advocacy.

- Funders: Availability of external financing is a critical constraint for many scaling initiatives. Accordingly, the engagement of funders along the pathway and the financing instruments they use are of particular importance for the scaling process. Figure 5 shows which stages of the scaling pathway different types of funders typically support. Research and innovation funders, which typically include governments, foundations, private firms, and individuals, tend to support the first two to three stage of the innovation-scaling spectrum. Challenge funders and foundations generally support R&D, proof of concept, and transition to scale. Large international non-governmental organizations and medium-size official funders tend to finance proof of concept, transition to scale, and also scaling; while vertical funds and large multilateral and bilateral funders support principally the last two stages (scaling and, occasionally, operating at scale). the first three stages generally depend heavily on grants, highly concessional official finance, or private impact investors, while the latter stages can and need to involve much broader ranges of funding, including loans, equity, guarantees, etc.

A key conclusion is that no single actor – research, innovator, implementor, intermediary, or funder – is likely to cover (or fund) the entire scaling pathway, which typically spans 10-15 years or more. In practice, this leads to serious gaps that tend to be especially severe in the middle stages. In innovation literature this has been referred as the “valley of death” which so frequently ends the scaling process. The gaps include disconnects between research organizations and innovation labs on the one hand, and implementing entities, including government ministries and the private sector, on the other; or these gaps can arise when NGOs and social enterprises that experiment with successful innovations find it difficult to get wider take up by government or commercial delivery channels.

Contributing to these gaps is the reality that funders supporting early stages generally do not systematically prepare for handoff to subsequent funders or to permanent providers, and those operating in the latter stages generally do not engage with funders of earlier stages in identifying suitable candidates for scaling and supporting a seamless handoff. This gap is perhaps most surprising for those funders that have in-house innovation labs but no effective link between the innovations supported by the lab and the financial programs supported by the main operational units in the same funder organization (see Box 4).

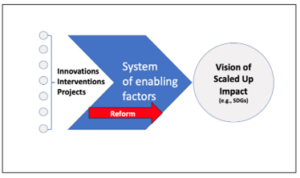

Scaling with a system change perspective

A second way of considering scaling is from the perspective of system change. In this approach to pursuing impact at scale, one looks first at the ecosystem of enabling and constraining conditions that shape the supply and demand for goods, services, and outcomes and that affect the achievement of development outcomes at scale. Figure 6 schematically reflects this perspective. A system approach starts with analysis of the prevailing economic, social, environmental, and political conditions (or a subset thereof) that generate a particular outcome (e.g., a target rate of growth, a reduction in poverty, or a reduction of CO2 emissions) and then explores what changes in the system are required to allow or bring about the desired outcome or to implement a particular intervention. The systems approach stresses the interconnectedness of different system components and the need to understand and – where necessary – reform the system or portions of it to achieve the desired outcome.

As was noted in section 2 above, the concept of “system change” is implicit in any serious discussion about scaling. Although pilot projects can sometimes circumvent systemic constraints and considerations, they will without exception confront those considerations as they increase their coverage and as the move towards institutionalization. But while scaling cannot afford to ignore the system, it has a choice to make about how much system change it can and wishes to take on and needs to recognize that introducing a change in a system requires high level support, careful planning, and sustained implementation – a pathway approach that in essence mirrors the scaling approach described above.

Kohl (2021) developed a classification of different types of scaling that is helpful to an understanding of the link between scaling and system change (see Table 2, next page). “Traditional scaling” (item 1 in Table 2) is not or very little concerned with system change. By contrast, “Scaling with system change,” “transformational scaling,” and “narrow systems change” typically involve a combination of complementary scaling and systems change but differ in the extent to which one or the other is seen as a priority. Broad system change involves a transformation of a complete system with generally little attention to scaling specific interventions. In practice, deliberate and planned system change tends to focus on specific areas of reform such as tax reform, agricultural policy reform, or introduction of carbon pricing, or on specific components in each of these areas.

Table 2. Overlap and complementarity between scaling and system change

| Type of scaling and/or system reform | Key characteristics |

|

The aim is to achieve the adoption of an innovation, with limited spread and depth, and no or only incremental systems change |

|

Like 1, but more spread and depth, with a focus also on systems change, but only in so far as necessary to support the scaling process |

|

Like 2, but a broader systems lens is applied than strictly necessary for scaling, and the scaling process is designed in part to transform the system. |

|

The aim is to change a particular aspect of a system or subsystem, potentially – but not necessarily – using a scaling approach |

|

The aim is to change an overall system in a comprehensive and transformational manner, with multiple entry points for reform and close attention to system-wide feedback loops |

Source: Adapted from Kohl (2021)

Any significant change in a system requires careful planning and sustained implementation, usually over extended periods. In effect, system change involves pathways of change that are very similar to the scaling of innovations. For example, the SOFF program (Box 5) to improve the functioning of weather and climate prediction systems involves a 10-year sequenced program of preparatory analysis of gaps in weather and climate observation infrastructure in the countries supported by the program, followed by investments to close the gaps, and then support for the operation and maintenance of the observation infrastructure created. Throughout, progress and impact are evaluated, and the program adapted as needed to achieve the long-term goal of minimum required observation density and quality under the binding standards agreed by the member countries of the World Meteorological Organization.

In sum, one can conclude that (a) scaling cannot afford to ignore the system but has a choice to make about how much system change it can and wishes to take on; (b) system change will in practice have to rely on a scaling approach to achieve particular reform goals; and (c) introducing a change in a system will generally require a pathway approach that in essence mirrors a scaling approach.

Scaling through projects

A large portion of development and climate change activity is designed and implemented through discrete time-bound projects with a beginning, a middle, and an end. Projects are typically prepared with a lead time that can be months or, for major undertakings, years. They have prescribed timelines, defined budgets, and specific results that are to be delivered by the end of the project, and typically include various requirements regarding the implementation process (procurement rules, social and environmental standards, etc.). Upon their completion, the success or failure of a project is generally assessed in terms of whether it achieved the targeted results on time and within budget, and less frequently and rigorously also in terms of the sustainability of its impact. The project approach has many advantages in organizing development action and is likely to remain the dominant organizational device for getting development investments done.

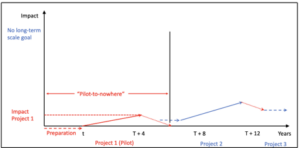

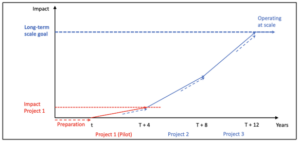

However, the project approach has critical limitations from the scaling perspective. In particular, the one-off, time-bound nature of projects is a serious constraint, as demonstrated in Figure 7. The red arrows at the bottom left indicate that a project (“Project 1”) requires a certain amount of time for preparation (the red dashed arrow), and then is implemented and delivers impact over several years (the solid red arrow) to reach a targeted impact level (the dashed red line). When the typical project ends, the project implementation units are frequently disbanded, and the results (or assets) created by the project are managed by whatever organization receives them for operation and maintenance.

Figure 7. Project scaling pathway – how it often is

Experience shows that frequently assets are not well operated and maintained and hence are not sustainable, with impact then declining and potentially disappearing entirely over subsequent years. More often than not, there is no deliberately planned follow-up to a project, on the presumption perhaps that a successful project will be picked up and replicated by someone. However, this presumption generally turns out to be wrong, since without a deliberate effort during project implementation to mobilize institutions, resources, and political support for the continuation and leveraging of the intervention beyond project end, there is unlikely to be scaling up following the end of the project. Even where projects are designed as “pilots,” supposedly testing innovative approaches, there is all too often no deliberate follow up, and these projects in effect end up as “pilots to nowhere.”

These difficulties apply not only for investment projects, but also for projects that aim at policy reform and strengthening technical capacity. The one-off, time-bound nature of such projects often means that a reform effort that by its very nature must be long-term in design is truncated at project end with little or no follow-up on implementation of policy reforms (e.g., implementing regulations for laws passed) and little assessment of the impact the reforms are designed to achieve. Similarly for technical assistance projects, the one-off, time-bound nature of projects, often employing foreign expertise with little country familiarity or longer-term interest, and a failure to systematically follow up after project end, means that little lasting benefit in terms of institutional strengthening is attained, let alone scaled.

These challenges associated with one-off, time-bound, and discontinuous engagement are prevalent in, but not limited to, projects funded by external (international) funders. They also apply for projects funded from national resources, due to political and business cycles affecting government priorities and funding, and due to the discontinuities in private investment decisions and financing.

Figure 7 also demonstrates a case where a successor project is developed building on the first (or pilot) project, but with a delay due to a lack of consideration of scaling and of adequate preparation of the successor project during the implementation of the initial project. The cost of discontinuity is reflected in the lower starting point in terms of impact and the relatively flat curve of impact for the successor project. As a result, the scale of impact remains limited. In any case, there is generally an absence of a clear, long-term scale vision or goal to drive and guide the scaling process and against which to measure progress. Progress is typically measured against the project’s impact target expressed as an absolute amount (e.g., people served or reached, tons of CO2 emissions avoided, etc.) or as a percentage increase relative to a baseline at the beginning or without the project, rather than in terms of progress towards a longer-term goal.

Figure 8 (next page) presents a different and preferable approach. Here, the initial project is used not only to test whether the intervention has the desired impact but also (i) defines a longer-term vision of a scale goal that significantly addresses the development problem; (ii) explores the enabling or constraining factors for potential scaling beyond project end, and ensures that the conditions for successful scaling and eventual sustained operations are (or are put) in place (i.e., demand for and ownership of the project intervention, institutional capacity, financing, political support, partnerships, etc.); and (iii) initiates a preparation effort that allows a follow-up project — or a handoff to a permanent source of implementation and funding –without a break after the end of the project. In other words, the project is used not only to achieve certain limited outputs during the project lifetime, but also to create the platform that allows sustainable scaling of the initiative beyond project end. If more than one project is needed prior to institutionalization, the focus of successive projects should include strengthening the systemic conditions for scaling until full institutionalization is achieved and the scale target is reached.

Figure 8. Project scaling pathway – how it should be

Source: Authors

The same organization and/or the same funder may be able to continue the scaling process for one or more successor projects. But more often than not, as was mentioned in Section 2 above in the discussion of the stages of scaling pathways, successor projects involve handoffs to other organizations (e.g., from one donor to another, from an NGO to government, or from an innovator to an existing private firm). Given the time and effort needed to secure successful handoffs, planning should begin with initial project design and continue during project implementation. Mid-term reviews, which are a frequent feature of project implementation, should include a focus on how to prepare for seamless continuation or handoff at the end of the project. Moreover, to the extent that projects are expected to lead to seamless follow-on projects or handoffs to permanent institutions, budget allocations need to be made to allow the preparatory work to be carried out by project teams, rather than adding the requirement as an “unfunded mandate” to the tasks project teams are expected to deliver on.

Note, however, planning for handoff alone is not enough. As emphasized throughout this paper, the enabling conditions for longer-term scaling must be considered and, to the extent possible, put in place as part of project design, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation, beginning on day one.

In sum, since for many development interventions, whether public or private, domestically or externally funded, the project approach will remain prevalent, achieving sustainable development impact at scale requires that projects be crafted and positioned as part of a longer-term scaling pathway along which they not only generate important development impact but also create the conditions for subsequent scaling and ultimately for sustained operations at scale and allow for effective hand-off from one implementer to another and from one funding source to the next. The case of long-term IFAD support for a highland development program in Peru through successive project cycles represents a case of successful scaling with a project-based approach (Box 6).

Specifically for funders, a few additional observations on the project approach apply:

- Some funders have recognized the need for more long-term engagement in the interest of replicating and scaling the interventions they support. They have done so by either systematically preparing a follow-on project during implementation of an initial project, or by developing “multiphase” projects that commit to a longer-term (say, 10-year) engagement in a program that defines a broad set of impact goals and the outlines of a pathway for achieving the goals in successive stages. Funding is also disbursed in stages, with flexibility built into the process to allow for assessment of how the intervention works out and for changes in program design as needed to achieve the desired outcome at the end of the program. If implemented effectively, the multiphase approach can be a good scaling strategy, but it requires funders to be able to make long-term financing commitments.

- The multiphase funding approach is sometimes referred to as “programmatic” financing. But it is important to distinguish this from the more common “programmatic” approach to funding, which provides finance for a collection of connected projects on a programmatic, i.e., coordinated, basis to exploit potential synergies and economies of coordination that promise to increase impact over and above what uncoordinated projects could achieve. While coordinated funding across a country strategy can have beneficial impact, this does not resolve the sequencing problem associated with the normal 10-to-15-year scaling trajectory. This requires that the individual projects be designed and implemented with a longer-term scaling perspective.

- In practice, the multiphase lending approach and the contemporaneous programmatic approach have each proven to be problematic due to difficulties by funders and their clients in committing to long-term funding arrangements, and due to the complexity of ensuring alignment in project preparation and implementation across multiple projects and funders.

- Provision of sustainable outcomes at scale depends on moving beyond projects by embedding change in institutions with the mandate, reach, capacity, and funding to provide the needed goods and services in perpetuity at scale.

A holistic approach to scaling with systems change in a project world – some practical suggestions

While presented as three separate perspectives or lenses in the preceding sections, these three approaches – scaling innovations, system change, and scaling with projects – are intimately linked and complementary. The “scaling of innovations” perspective focuses on the different stages of the pathway from innovation to impact at scale and on key considerations for actors along the way. The “systems change” perspective puts the spotlight on the critical importance of enabling factors and actors in the ecosystem in which scaling happens, and the complementarities between scaling and system change. The “projects” perspective considers a practical way to organize development action and what needs to be done to have it not hinder, but support scaling and system change. All three perspectives yield important insights for the pursuit of sustainable impact at scale. The most important are briefly summarized in this section.

An inclusive vision of optimal impact at scale

For all three perspectives, it is important that there be a long-term vision of sustainable impacts at scale linked to the development problem to be addressed. In many cases, this vision can and should be linked to the Sustainable Development Goals, and appropriately scaled to reflect the mandate and reach of the particular actor. There are four corollaries to this consideration:

- The vision needs to focus on optimal, not maximal scale, because of (1) potential tradeoffs among multiple goals; (2) equity considerations; (3) unintended consequences; and (4) the fact that beyond a certain scale incremental costs may outweigh benefits.

- The scale vision needs to be inclusive in the sense that the vision is determined in an inclusive manner based on contributions from the major stakeholders and ultimately is owned by national actors rather than driven by external funders.

- The vision needs to be just, in the sense that losers are compensated to the extent possible, and that women, girls and youth, and other disadvantaged groups or hard-to-reach (“last-mile”) communities are included in the scaling vision and process.

- Scaling with system change is a long-term process that often will take 10-15 years and requires a sequence of projects/programs prior to full institutionalization.

- At the same time, this process needs to be pursued with urgency and with well-defined intermediate results. This is critical to sustaining momentum and demonstrating impact and value-added to stakeholders.

Scaling with systems change needs to be sustainable and transformational, not merely transactional

As the preceding discussion should have made clear, sustainability and scaling are closely intertwined, since the ultimate goal of scaling is sustainable impact at scale. If a solution is not sustainable, it should generally not be scaled; if it is not scalable, the same obstacles that impede scaling will likely also limit sustainability.

Much of the current discussion about scaling focuses on the need to mobilize additional sources of development financing to support bigger and more ambitious projects. This “transactional” view of scaling has value since it reflects the chronic underfunding of many development and climate initiatives, but it needs to be combined with a “transformational” perspective that looks beyond the end of the intervention or project time horizon. Transformational scaling asks what needs to be done during project implementation to ensure continued scaling and sustainable results at scale after the project ends by ensuring that there are motivated and capable implementing organizations (“doers” at scale) and a sustainable and scalable business model or funding source (“funders” at scale), and that the enabling conditions are put in place to support continued scaling and delivery beyond project end.

A focus on enabling systemic conditions is critical

Whether one takes enabling conditions as given or to be changed, they need to be considered explicitly, including:

- Demand – market demand or community demand – for the intervention must be present or created.

- Ownership of the scaling vision, innovation (or intervention) and scaling pathway by the implementing organization(s) must be assured. This is especially true for governments in their relationship with external funders. In these cases, government acquiescence is not enough; true ownership is essential for sustainable scaling and operation at scale where governments are the implementers and/or funders at scale. For funders, “localization” in this context means engaging stakeholders as drivers of the scaling process.

- Sustainable and scalable financing by the recovery of costs from beneficiaries or from budgetary resources must be assured to cover costs, which in turn must be carefully assessed and controlled – not just transactionally for one project, but transformationally for the scaling pathway.

- Institutional capacity must be created to support the process of service delivery and scaling with appropriate adaptations over the different stages of sequential projects. Special attention must be paid to ensure institutional platforms are created which enable the sustainable operation at scale – the last stage of the scaling process.

- Policies and incentives need to be put in place to support the pathway towards sustainable impact at scale. These policies and incentives often must be adapted to the particular stage in the scaling process. For example, certain subsidies that may be appropriate early in the scaling process may have to be phased out as the scaling process proceeds.

- Partnerships are critical – public-private partnerships; partnerships between official, charitable, and private funders; and funder-implementer partnerships. These partnerships need to be transformational, i.e., support the long-term scaling pathways with appropriate handoff from one partner (implementer or funder) to the next at the end of a scaling stage or at project end. This requires effective prior engagement and coordination. One-off, transactional partnership (e.g., co-financing) helps in the short term, but does not by itself support the scaling pathway.’

- Politics – local, national, regional, and global – is an inevitable enabling or constraining factor for scaling, especially as the scale of impact grows and as systemic changes are pursued as part of the scaling process. Anticipating and addressing political opportunities and obstacles by considering winners and losers from the scaling process is one important area for attention; and it is important to consider how best to insulate the intervention from political cycles, changes in political leadership, etc. by inclusive stakeholder engagement.

- Effective and sustained leadership is required for laying out an appropriate vision of scale and for driving the process of scaling with systems change. However, this leadership must ensure buy-in and ownership from a wide range of stakeholders.

Planning and implementing scaling with system change

There are well-developed and understood planning and implementation systems for projects, with identification, appraisal, implementation, and ex-post evaluation systems that include tools such as log-frames, impact evaluation, and results measurement techniques. However, most of these approaches and tools focus narrowly on the project and not on whether the interventions supported under the project are suitable for scaling or whether the enabling systemic conditions that are needed for sustainable scaling beyond project end are in place. This must be rectified by incorporating some of the principles, approaches, and tools for planning and implementing scaling pathways — and for assessing risks — that have been developed over the last two decades. Of particular interest are scalability assessment tools and institutionalization mainstreaming trackers. The former help assess whether an intervention is scalable and what needs to be done to increase its prospects for being scaled; the latter help assess to what extent scaling has been integrated into the operational modalities of public institutions.

Gathering and applying evidence for scaling – monitoring, evaluation, and learning

Evidence is a critical ingredient for successful scaling, including evidence on (i) the nature and scale of the development problem; (ii) the core elements of the innovations and interventions and the impact of various elements on sustainability and scalability; (iii) the systemic conditions that enable and constrain sustainable scaling; and (iv) the winners and losers of the scaling process, and the effects on disadvantaged population groups and regions. Monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) are critical during implementation of the scaling pathway and must be focused not only on measuring delivery of inputs and assessing impact, but also on (i) the viability of the scaling pathway; (ii) whether and how the enabling and constraining systemic conditions affect scalability; and (iii) whether changes in scaling strategy or in the intervention itself would aid scaling. During the scaling pathway, MEL approaches and metrics may have to adapt to reflect the different challenges and opportunities at each stage. And the findings of MEL must be fed back into the implementation process with adaptation of the intervention and the scaling pathway, starting with the vision and goals set, the content of the intervention, and how the enabling and constraining conditions are addressed.

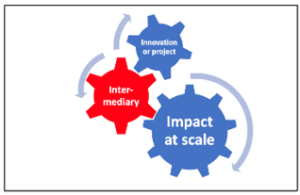

Intermediation for scaling with system change

Intermediation in the private sector is commonly performed by investment bankers, venture capitalists, and strategic consultants. The public sector and social enterprise lack a viable equivalent despite evidence that effective scaling badly needs such intermediary institutions to support the scaling process (see Figure 9). Intermediation involves various functions: helping the leadership in setting an appropriate vision of scale; helping to assemble investment packages and convene potential funders; providing technical support to implementers directly related to scaling; analyzing systemic constraints and implications and designing reform measures to address them; organizing consultative and participatory processes for stakeholders; supporting the development of results measurement and management frameworks and practices; and sharing lessons and tools for scaling with systems change. Funders can play an intermediation role for scaling, but usually only on a temporary basis.

Institutionalizing and mainstreaming scaling in development organizations

A critical aspect of scaling is that it needs to be systematically introduced – i.e., mainstreamed – into the institutional goals and practices of all relevant actors, including innovators, implementers, intermediaries, and funders. This requires that (i) sustainable impact at scale is an essential element of the institutional mission and strategy; (ii) the leaderships of the organizations identify and pursue the scale goal as a key institutional priority underpinning the successful achievement of all other specific institutional goals; (iii) organizational processes, guidelines, resources, capacities and incentives be oriented towards the scaling objective; (iv) results metrics and monitoring, evaluation, and learning reflect the scaling agenda; and (v) the scaling orientation of the organization is subjected to intermittent independent external evaluation to ensure that scaling is indeed institutionalized and mainstreamed and that emerging lessons are learned and internalized through adaptation of the organization’s approach to scaling.

The role of incentives in supporting the scaling process

This section concludes with a comment on the important role of incentives at the level of the ecosystem within which scaling takes place and at the level of an organization that is to support scaling.

Looking first at the systemic level, standard economic theory postulates that in a well-functioning market economy without monopolies, monopsonies, externalities, and distorting government policies, the profit motive of private enterprises and competition among them will generate price signals that incentivize efficient economic growth, i.e., scaling. Of course, in real life the stringent efficiency conditions generally do not prevail; moreover, market outcomes may not be consistent with society’s social goals of equity and inclusion. For these reasons, public intervention, i.e., policy, is required to generate incentives for private actors to scale and sustain efficient, equitable and inclusive outcomes.

For public agencies – national, subnational, and international – processes and incentives are more complex and need to be aligned to support the coordinated scaling of government priorities and strategies. This is likely most easily achieved in sectoral or subsectoral processes (also known as “country platforms”) in which an alignment of key actors through appropriate incentives is pursued. The Global Financing Facility for Every Woman Every Child (GFF) is an organization that aims to induce such alignment for the achievement of universal health coverage, with a special focus on women’s and children’s health. (See Box 7)

Consider next incentives at the organizational level: Managers and staff in the organizations involved in the scaling process need incentives to focus on those elements in their engagement with innovations, systems change, or projects that are needed for an effective scaling process. In practice, organizations often have processes and incentives in place that encourage individual actors and teams in the organization to focus mostly on innovation, on short-term effort system change, and on one-off projects and their short-term impacts. It is therefore essential that, as part of the mainstreaming effort mentioned above, funders focus on how to ensure that the incentives for their own managers and staff are such that they will be motivated to align with the scaling objectives of the organization. This includes clear messaging from the top leadership, operational processes that demand a focus on scaling, and accountability by each individual or team for aligning themselves with the organization’s scale goals through appropriate job descriptions and performance metrics. These incentives must be complemented by ensuring the provision of the administrative budget resources, training, and knowledge management support that allows for managers and staff to effectively implement a scaling approach in the context of their assignments.

Concluding comments on the core elements of a sustainable scaling framework

The most important aspects of the framework for scaling with system change discussed in this paper can be encapsulated in seven basic questions that development practitioners need to address as they plan and implement interventions with the aim of achieving sustainable impact at scale:

- What is the development problem and the vision of sustainable impact at scale that is needed to address the problem?

- What are the core elements of the innovation, intervention, or project, and are they scalable?

- What is a potential scaling pathway from innovation, intervention, or project to the achievement of the scale vision, and who are the principal actors that need to fund and drive the process forward?

- What are the principal enabling and constraining system conditions that need to be considered or addressed with reforms for scalability?

- What is the plan for implementing the scaling pathway, what resources are needed to put it in place, and how can one or more intermediary organizations support the process?

- What evidence is needed to support decision-making along the scaling pathway, and how does MEL need to be designed to inform the scaling process and its adaptation?

- And perhaps most importantly, what happens after the current stage in the scaling pathway, or after the current project ends?

If these questions are asked for every innovation, project, and intervention, it will signal a fundamental shift in mindset from pilots-to-nowhere and short-lived efforts to support for scaling pathways capable of achieving transformative change for sustainable impact at scale.

References

Andrews, Matt, Lant Pritchett, and Michael Woolcock (2016). “Doing Iterative and Adaptive Work.” CID Working Paper Series 2016.313, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Artemiev, Igor and Michael Haney (2002). “The Privatization of the Russian Coal Industry: Policies and Processes in the Transformation of a Major Industry.” Policy Research Working Paper, No. 2820. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/19258

Begovic, Miliça, Johannes F. Linn, Rastislav Vrbensky (2017). “Scaling Up the Impact of Development Interventions: Lessons from a review of UNDP Country Programs.” Global Economy & Development Working Paper 101. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/global-20170315-undp.pdf

European Parliament (2020). “Understanding development effectiveness: Concepts, players and tools.” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2017/599401/EPRS_BRI(2017)599401_EN.pdf

IDB (2023). Scaling Innovations in Development: The Experience of IDB-Lab. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/viewer/Scaling-Innovations-in-Development-The-Experience-of-IDB-Lab.pdf

Guerrero, Isabel, Siddhant Gokhale and Jossie Fahsbender (2023). Scaling Up Development Impact. https://www.amazon.com/Scaling-Development-Impact-Isabel-Guerrero/dp/B0CNWS7W64

Hartmann, Arntraud and Johannes F. Linn (2008). “Scaling Up: A Framework and Lessons for Development Effectiveness from Literature and Practice.” Wolfensohn Center for Development Working Paper No. 5. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/10_scaling_up_aid_linn.pdf

IDIA (2017). “Insights on Scaling Innovation.” https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6295f2360cd56b026c257790/t/62a1d43829d380213485d4f9/1654772794246/Scaling+innovation.pdf

Igras, Susan, Larry Cooley and John Floretta (2022). “Advancing Change from the Outside In: Lessons Learned About the Effective Use of Evidence and Intermediaries to Achieve Sustainable Outcomes at Scale Through Government Pathways.” Scaling Community of Practice. https://scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Advancing-Change-from-the-Outside-In-1.pdf

Kohl, Richard (2021). “Scaling and Systems Change: Issue Paper.“ Scaling Community of Practice. https://scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/bp-attachments/8666/Scaling-and-Systems-Change-Issues-Paper.pdf

Kohl, Richard and Johannes F. Linn (2021). “Scaling Principles.” Scaling Community of Practice. https://scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/bp-attachments/8991/Scaling-Principles-Paper-final-13-Dec-21.pdf

Kohl, Richard, Johannes F. Linn and Larry Cooley (2024). “Mainstreaming Scaling in Funder Organizations: Interim Synthesis Report.” Scaling Community of Practice. Forthcoming

Ben Kumpf and Angela Hanson (2023). “Innovation Portfolio Management for International Development Organisations – Part 1.” Observatory of Public Sector Reform. https://oecd-opsi.org/blog/innovation-portfolio-for-development-part1/

Levy, Santiago (2006). Progress against Poverty. Washington, DC. Brookings Press.

Linn, Johannes F. (2011a).“Scaling Up with Aid: The Institutional Dimension.” in H. Kharas, K. Makino and W. Jung, eds., Catalyzing Development: A New Vision for Aid. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Linn, Johannes F. 2011b. “It’s Time to Scale Up Success in Development.” Meinungsforum Entwicklungspolitik, No. 7. KfW Entwicklungsbank.

Linn, Johannes F. 2013 “Incentives and Accountability for Scaling Up.” In Lawrence Chandy, Akio Hosono, Homi Kharas, and Johannes F. Linn (eds.), Getting to Scale: How to Bring Development Solutions to Millions of Poor People. Washington, DC: The Brookings Press https://www.amazon.com/Getting-Scale-Development-Solutions-Millions/dp/0815724195

Linn, Johannes F. (2015). “Scaling-up in the Country Program Strategies of International Aid Agencies: An Assessment of the African Development Bank’s Country Strategy Papers.” Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies. Volume 7, Issue 3. https://doi.org/10.1177/0974910115592

Linn, Johannes F. (2021). “Evaluation approaches to scaling – application and lessons.”

International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. https://www.3ieimpact.org/blogs/evaluation-approaches-scaling-application-and-lessons

Linn, Johannes F. (2022). “Three Case Studies Applying the Scaling Principles of the Scaling Community of Practice.” Scaling Community of Practice.

Linn, Johannes F. (2023a). “Scaling Up the Impact of Development Programs Must Complement Other Approachs to Achieve the SDGs and Climate Goals.” Global Summitry E-Journal Special Issue 2023. https://globalsummitryproject.com/special-issue-2023/scaling-up-the-impact-of-development-programs-must-complement-other-approaches-to-achieve-the-sdgs-and-climate-goals/

Linn, Johannes F. (2023b). “Mainstreaming Scaling Initiative case Studies: Systematic Observations Financing Facility (SOFF).” Scaling Community of Practice. https://scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Scaling-Up-at-SOFF-FINAL.pdf

Linn, Johannes F. (2024). “Mainstreaming Scaling Initiative case Studies: Global Financing Facility (GFF).” Scaling Community of Practice. (Forthcoming)

Massler, Barbara (2012) “Empowering Local Communities in the Highlands of Peru.” In “Scaling Up in Agriculture, Rural Development, and Nutrition.” Edited by Johannes F. Linn. 2020 Vision, Focus 19. International Food Policy Research Institute.

https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/126977/filename/127188.pdf

McLean, Robert and John Gargani (2019). Scaling Impact: For the Public Good. New York: Routledge https://idrc-crdi.ca/sites/default/files/openebooks/scalingimpact/index.html

MSI (2012). “Scaling Up – From Vision to Large-Scale Change.” https://www.msiworldwide.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Scaling-Up-Framework.pdf

MSI (2021). “Scaling Up from Vision to Large-Scale Change: Tools for Practitioners, 2021.” https://www.msiworldwide.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ScalingUp_toolkit_2021_v5_0.pdf

Nothstine, Kathy, Olivier Usher, and Teodora Chis. (2022) “Challenge funds – what, who, and why?” Challenge Works. https://challengeworks.org/thought-leader/challenge-funds-what-who-and-why/

OECD (2022). Tackling Policy Challenges Through Public Sector Innovation: A Strategic Portfolio Approach, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/052b06b7-en

Scaling Community of Practice (2022). “Scaling Principles and Lessons.” https://scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Scaling-Principles-and-Lessons_v3.pdf

Swaroop, Vinaya (2016). “World Bank’s Experience with Structure Reforms for Growth and Development.” Discussion Paper No. 11, MFM Global Practice. The World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/826251468185377264/pdf/105822-NWP-ADD-SERIES-MFM-Discussion-Paper-11-PUBLIC.pdf

UNDP (2022). “System Change: A Guidebook for Adopting Portfolio Approaches” https://www.undp.org/publications/system-change-guidebook-adopting-portfolio-approaches

World Bank (2017). “Multiphase lending.” https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/203081501525641125/pdf/MPA-07192017.pdf

Wyss, Molly and Johannes F. Linn (2021). “Tracking an education initiative’s integration into government: An institutionalization tool.” Commentary. Brookings.