Preface: A High-Level Summary of Findings

This report presents a synthesis of findings from a The main findings of the report are also summarized in a Policy Brief.

The world faces enormous development, humanitarian, and climate challenges at the very time when traditional sources of support are suffering major cutbacks. This puts a premium on ensuring that the available financing shifts its focus from funding innovative standalone projects to increasing the capacity of governments, social enterprises, and the private sector to deliver long-term impacts that address global problems sustainably and at scale.

International development and climate funder organizations play a key role in supporting the pursuit of sustainable impact at scale, but in the past they have in general not focused adequately on the scaling agenda. Recognizing this, funders are increasingly focusing on impact at scale. This report assesses to what extent and how 28 funders organizations have mainstreamed consistent approaches to scale and scaling into their operational practice and what lessons can be learned from their experience. In this context, “mainstreaming scaling” means systematically integrating scaling into funders’ organizational objectives, strategies, business models, operations, resource allocation, managerial and staff mindsets and incentives with a focus on impact and results, not disbursements and short-term outcomes achieved.

Case studies for this study were purposively selected to examine a wide range of funder organizations known to be making serious efforts to mainstream scaling into their policies, programs and priorities. Following an “action research” approach, funder staff wrote or supported the writing of all 28 case studies.

The main findings of the report can be summarized as responses to the key questions addressed:

To what extent have funder organizations mainstreamed a systematic focus on scaling?

- Scaling is a topic of growing interest in the funder community.

- Across the 28 organizations, there is progress with mainstreaming, but unevenly so.

- The needle is moving in the right direction, but too slowly.

Which key dimensions of scaling should funders prioritize and support?

- The distinction between transactional and transformational scaling is of central importance.

- Transformational scaling requires a long-term vision of scale and scalability from the beginning, an explicit and sustained focus on systemic change, persistence in engagement, a focus on equity and inclusion and on localization and partnerships, and frequent adaptation in response to lessons learned.

- A focus on support for transformational scaling is easier for some categories of funder than for others, with large official funders most challenged.

What factors enable or drive the mainstreaming of scaling within funder organizations?

- Specific drivers, as detailed in the case studies, relate to leadership, vision and goals, operational policies, internal resources and incentives, knowledge and monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning.

In which areas have funders made greater progress, and where has progress been more limited?

- Overall, funders have made the most progress in incorporating a scaling focus in statements by agency leadership and embodying it in mission statements, though this focus often fails to distinguish between transformational and transactional scaling.

- There is frequently a gap between high-level aspirations and implementation of the needed internal changes in incentives, systems and metrics.

- The ability and readiness to stay engaged and persistent over time in scaling support is most evident in vertical funds, INGOs, and some foundations.

- Trade-offs do not get the attention they merit.

What are the principal challenges encountered?

- The traditional project model is a pervasive problem because of its focus on one-off results, its failure to consider the needed enabling conditions for sustainability and scalability, and its lack of consideration of what happens beyond project end.

- Reluctance to engage in strategic partnerships and ineffective handoff from one funder to the next remain serious challenges.

- “Unfunded mandates” for midlevel management and staff and the resulting disincentives for them are a hidden hazard.

What lessons emerge for funders seeking to mainstream scaling?

- The main lessons for funders considering mainstreaming are summarized in the table below:

| Support key transformational scaling practices

· Initiate scaling from the beginning · Incorporate scalability criteria and assessment into all stages of scaling · Integrate support for systems change with scaling · Explicitly address equity and inclusion and anticipate unintended consequences · Double down on country ownership and localization · Invest in partnerships with other funders · Embed scaling into MEAL · Elevate and strengthen intermediary roles |

Put in place key enablers of mainstreaming transformational scaling

· Drive scaling through leadership · Focus vision, goals, and targets on transformational impact at scale · Align operational policies and practices and time horizons with scaling · Dedicate organizational resources and capacity to scaling · Develop analytical tools and knowledge and esp. an incentive and culture for scaling · Go beyond decentralizing operations in supporting localization and scaling. · Use M&E to drive effective mainstreaming · Plan for appropriate sequencing and adapting the mainstreaming process · Manage tradeoffs and tensions transparently |

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE

I. Introduction: Background, Motivation and Scope of this Report

A. The Background of This Report

The pursuit of sustainable development and climate impact at scale – or scaling, for short – has been receiving growing attention in the international development community over the last few years. The exponential growth of the Scaling Community of Practice (SCoP) membership from some 40 participants at its founding in 2015 to more than 5,000 in 2025 is one indicator of this interest. There are many others, including statements by leaders of major development finance institutions, such as the World Bank’s President in his speech at the International Monetary Fund (IMF)/World Bank Annual Meeting in October 2023, and the inclusion of achieving impact at scale now found in many mission statements of international and national development agencies.

This is largely due to recognition that traditional approaches to development and climate finance are not having the needed impact relative to the size of the problems, as evidenced by the fact that the world is significantly off track to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Paris Agreement objectives by 2030. In addition, there is general acknowledgement that despite their tremendous promise, investments in innovation have not realized their potential. That underperformance reflects not only the scale of resources, but also how financing is structured, sequenced, and governed.

Following years of increases, official development assistance (ODA) peaked in 2023, declined by 9% in 2024, and is projected to decline by a further 9-17% in 2025.While donors, national governments and the private sector could and should allocate more financial resources to meet the development and climate challenge, that is an unrealistic expectation given current political realities. Even if the political situation were to improve, it is unlikely that the quantity of funding will ever meet the need given the size of the financing gap. Experience also suggests that money alone will not do the trick.

Two additional considerations add weight to the urgency for reform. There is strong evidence regarding the need for larger, longer, and more flexible funding. Despite this, fragmentation and multiplication of the sources of external funding paired with reduction in the duration and size of funding packages have increased rather than diminished the prominence of small, short, single-donor, one-time projects.

The second major development is the increasing demand for local ownership (“localization”) to replace local concurrence as the foundation for effective development. Rooted in considerations of development effectiveness as well as power redistribution, the groundswell of support for localization now comes from voices across the political spectrum. In that regard, it is of particular concern that three out of every four projects funded by official development assistance continue to be implemented by third parties rather than by host governments.

For these reasons and more, the scaling agenda has merged with the movement to maximize the catalytic and value-added impact of whatever external financing is available.

In this understanding, scaling is not simply spending more or doing more, though the term is often used that way. Similarly, while grounded in the concept of increased development effectiveness, it goes beyond merely ensuring positive or growing returns on investment. It involves achieving economies of scale, scope, continuity, and cooperation so that greater impact (breadth and depth) can be achieved with whatever financing can be mobilized. For funders, this means that implementation is sustainable and that scaling by domestic actors continues after funder efforts end and reaches most, if not all, of the people and places needed to address development and climate challenges. While some organizations have made this kind of distinction rhetorically, they often blur or fail to maintain them in practice, particularly in large organizations.

Despite this heightened buzz around scaling and many examples of successful scaling, there is a growing consensus among development observers that not enough is being done by the principal development actors – governments, private investors, civil society, and development funders – to pursue scaling systematically. Documented cases of effective scaling continue to be linked mostly to specific interventions, individual initiatives, or fortuitous circumstances rather than the result of deliberate organization-wide strategies and their implementation. The issue is not a lack of examples, but a lack of institutionalization and repeatability.

Against this backdrop, the SCoP launched the “Mainstreaming Initiative” in early 2023 as a three-year “action-research” effort to study mainstreaming of systematic approaches to scaling in a cross-section of organizations that are funding international development and climate action. This followed a year-long preparation process that included a background paper and intensive discussion among the SCoP’s members in two SCoP Annual Forums and a number of webinars. The purpose of this initiative was to (i) assess progress to date, (ii) develop lessons learned, and (iii) disseminate those lessons to encourage and inform further mainstreaming by interested organizations. To facilitate learning, the Initiative focused on funders interested in partnering with the SCoP and known to have made some progress in mainstreaming scaling. This paper reports on the results of the three-year Mainstreaming Initiative.

At the core of the Mainstreaming initiative lies the evidence collected in 28 case studies of official multilateral and bilateral donors, vertical funds, innovation funders, research institutions, private foundations, and INGOs, all of which fund development and/or climate action. In addition, the Initiative carried out a number of studies to underpin and extend its overall findings:

- An Interim Synthesis Report prepared in June 2024, halfway into the Initiative;

- Deep dives on scaling lessons for funders in Education and Agri-Food, and for Foundations;

- Supporting analyses on: (1) a survey of recipient perspectives; (2) evaluation policies and practices of official funders; (3) promising practices by innovation funders; (4) the role of big bets and open call competitions; (5) the relationship between scaling and country platforms; and (6) the relationship between scaling and localization;

- A Mainstreaming Tracking Tool for monitoring and guiding funder policies and practices related to scaling;

- A publication on Scaling Fundamentals;

- A publication on why scaling is essential for the achievement of the SDGs:

- SCoP Scaling Principles and Lessons and support for the preparation of a Scaling Guide published by OECD-DAC; and

- A series of blogs, convenings, and webinars on these topics.

The remainder of this introductory section explains why the SCoP and we as project leaders and authors have focused our on funders as a first step and what is the nature of the action-research approach that we have chosen. It is the long-term aim of the SCoP to support mainstreaming of scaling in the wider ecosystem of development and climate action. Section II present a bird’s eye view of funder roles and progress with mainstreaming support for scaling in their operational practice. Section III responds to the question of what are the scaling practices that funder organizations should support as they consider mainstreaming scaling in their funding practices – the focus here is on how to support transformational scaling. Section IV assess in detail how transformational scaling practices can be effectively mainstreamed into funder operations – by considering key enabling factors that can drive and support funder’s systematic approach to supporting scaling on the ground. Section V takes a look at the mainstreaming experience to date by broad categories of funder organizations – large official funders, vertical funds, innovation and research funders, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), foundations, and funders of big bet and open call competitions. The report closes with a summary of findings and lessons, recommendations for the funder community, and a call to action.

B. Focus on External Funders and Their Challenges in Providing Support for Scaling

Why the primary focus on external funders? Funders generally do not directly implement development programs, projects or policy changes. And, the aggregate resources they provide represent a small proportion of the funds needed to achieve key development and climate results. Those resources they do provide, however, often represent the lion’s share of the discretionary resources available to develop and scale new strategies and interventions, especially in the least developed countries. This creates a tension between funders’ limited financial share and their disproportionate influence over design, incentives, and accountability.

Experience suggests that external funders exercise outsized influence on program goals, strategies, results, and deliverables of the organizations and projects that they fund. Indeed, one of the motivations for this initiative was that many INGO members of the SCoP wanted to integrate scaling into their projects but were unable to obtain funding from donors. As such, funders can potentially serve as champions for scaling, and at the least can ensure that their funding practices and technical support facilitate, rather than impede.

Unfortunately, our analysis suggests that in many cases funders inadvertently create obstacles to scaling, obstacles that are systematic rather than idiosyncratic. The funder practices most frequently cited as compromising scaling efforts include:

- The project mindset – timebound funding delivers outputs, not sustainable impact. Funders typically support time-bound (2-5 year), one-off projects that focus on delivering outputs or at best outcomes, but not necessarily development impact. Moreover, they typically focus on outputs that can be achieved during the project’s duration, but not beyond project closeout.

- Misaligned incentives and metrics. Funder staff are often rewarded for presenting projects to their management and boards, and for disbursement, on-time delivery, and achieving their output objectives by project end. Staff receive less recognition, if any, for supporting ambitious longer-term goals of scale and sustainability. Similarly, the design and implementation of projects do not look to ensure, or measure, sustainability and scalability by others beyond project end. Follow-up to previous projects is often less valued by management than starting new ones. These incentive structures are often reinforced by governance and board-level expectations, not just staff behavior.

- Lack of alignment with domestic priorities. Funders often fail to align adequately with national priorities and ownership.

- Institutional strengthening and capacity building are missing, inadequate, or not targeting sustainable scaling. While many funders do some institutional strengthening and capacity building during the project lifetime, often these are incomplete given short project duration. More importantly, they frequently fail to address critical constraints on financial resources that stand in the way of long-term, sustainable scaling.

- Poor donor coordination, duplication, and burdensome siloed reporting versus mutually reinforcing activities. Despite decades of efforts at and exhortations for coordination and collaboration, funders operating in the same development space (geography, sector, thematic area, etc.) continue to evidence poor coordination, siloed reporting systems, duplicative efforts, etc. While partnerships are almost always necessary for successful scaling, international development and climate funders continue to struggle to overcome systemic obstacles to successful collaboration.

- Innovation funding has not been combined with sufficient support for scaling. Supporting “innovation” has become increasingly popular in the past fifteen years, as demonstrated by the proliferation of innovation and challenge funds, incubators, and accelerators. In too many cases, however, such approaches have not been accompanied by efforts to address the shortcomings of local systems and enabling environments that limit scaling and perpetuate development problems. Many innovation funders now provide funding for Transition to Scale as well as non-financial support like coaching, and more institutions work with innovators to connect to the next stage of funding. Still, too many continue to indulge in “magical thinking,” presuming that scaling will happen spontaneously or is the responsibility of unspecified “other institutions.” Innovation funding generally has not created institutions akin to the role venture capitalists play in taking their investments to market (“catalytic intermediaries”), resulting in the loss of enormous potential.

- Monitoring and Evaluation tracks outputs and outcomes, not impact. Project monitoring and evaluations focus on delivery against project plans, timely disbursement of funds, narrow results targets and impact. Monitoring and evaluation processes usually fail to generate data on scalability to support future scaling efforts and rarely examine whether projects put in place conditions for sustainability and scaling impact beyond project end. More specifically, these systems and metrics typically do not distinguish between need and demand; evaluate the impact and cost effectiveness of competing approaches; assess complexity and the extent of changes from existing behaviors and practices required by adopters and implementers; measure unit costs and evaluate potential for economies of scale; identify the role of context, social issues, and the political economy across relevant stakeholders; or assess constraints to scaling in the policy enabling environment or relevant market systems.

These concerns were confirmed by recipients of external development funding who were consulted as part of the Mainstreaming Initiative (see Box 1).

| Box 1: The recipient perspective of funder support for scaling

“This report examines recipients’ perspectives on how funders’ actions and requirements affect their capacity to scale development interventions effectively and sustainably. Drawing on key informant interviews, written stories, and a focus group, this report provides insight into recurring challenges and identifies actionable opportunities to improve funder-recipient dynamics.” “The report finds that, according to recipients, funders vary widely in their understanding and support for scaling. Recipients often lack the longer-term, flexible, and adaptive funding necessary to scale. Proposal processes are cumbersome and often misaligned with scaling goals, emphasizing compliance and immediate outputs over the adaptive learning and flexible approaches necessary for sustainable impact. Reporting frameworks are largely focused on short-term metrics rather than iterative progress, limiting their utility in scaling efforts. However, monitoring and evaluation provide opportunities for adaptive program management, if flexibility is allowed. Relationships with funders emerge as a central factor, with trust-based, collaborative engagements enabling more effective scaling. Foundations, while providing greater flexibility and relational support, typically offer smaller grants that limit their overall impact.” Source: Charlotte Coogan (2025) https://scalingcommunityofpractice.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Recipient-perspective-FINAL-2025.06.19.pdf |

C. The Case Studies of Funder Mainstreaming Experience

The Mainstreaming Initiative organized case studies of international development and climate funder organizations that explored six main questions:

- To what extent have funder organizations mainstreamed a systematic focus on scaling?

- Which key dimensions of scaling should funders prioritize and support?

- What factors enable or drive the mainstreaming of scaling within funder organizations?

- In which areas have funders made greater progress, and where has progress been more limited?

- What are the principal challenges encountered?

- What lessons emerge for funders seeking to mainstream scaling?

Underpinning the case studies are the definitions, principles, and lessons that have emerged from research on good practice in scaling, as found in the Principles and Lessons of Scaling compiled by the Scaling Community of Practice and in the SCoP paper on Scaling Fundamentals. Box 2 summarizes the definitions we use in this report.

In the spirit of a highly collaborative “action research” undertaking, the case studies were either prepared by experts from within the funder organizations with support from the Scaling Community of Practice or written by Community of Practice members with cooperation from the organizations. The case studies were guided by a broad set of questions identified in the Concept Note for the Mainstreaming Initiative (see Annex 1) and adapted in each case to the specific conditions of the funder organization under review. Funding for the case studies was provided by the Scaling Community of Practice (including a grant by the Agence Française de Développement), by financing and in-kind contributions from the case study organizations, and by pro bono contributions of the case study authors.

| Box 2. Definitions

· Scale: sustainable impact at large scale, where large is defined as a significant share of the problem. · Scaling: actions taken over time in pursuit of sustainable impact at scale. · Transactional scaling: doing more with one-off interventions – more resources, larger projects, more co-financiers – and measuring success in terms of the scale of funding and results against baseline achieved by a project’s or program’s end. · Transformational scaling: delivering long-term sustainable impact at a large scale beyond a project’s lifetime and emphasizing a viable business or funding model, usually accompanied by a significant effort at sustainable systems change – and measuring success in terms of impact relative to the size of the problem, not against the baseline. · Mainstreaming scaling: integrating support for sustainable impact at scale into the operational mission, goals, policies, resource allocation decisions, managerial and staff incentives, and monitoring and evaluation methodologies. · Doer: a domestic implementing, delivery, or producing organization that continues to provide the product or service and has the capacity, infrastructure, incentive, and organizational resources to do so. · Payer: a financing mechanism or business model that sustainably funds the activity from recurring domestic or other resources. · Funder: a third-party, often international, payer organization. · Systems change: policy, legal, or regulatory reforms to the public sector enabling environment; action to strengthen public sector institutions and market systems; or changes to social norms and beliefs. · Sustainable: impact endures over time in the following regards: (i) political: government, champions, or stakeholders provide ongoing support; (ii) institutional: implementing organizations have the capacity and other resources needed; (iii) financial: there is a viable source of ongoing funding, either public, private or mixed; and (iv) effectiveness: impact on beneficiaries or end-users suffers minimal decline or degradation. |

The mix of organizations covered is purposely diverse (see Table 1, next page). It includes: (i) large bilateral and multilateral funders that finance development projects across a broad range of sectoral and thematic areas; (ii) multilateral vertical funds that focus more narrowly on specific sectors, subsectors, or thematic development or climate topics; (iii) innovation funders and research organizations; (iv) large INGOs that provide grants and implement donor projects; and (v) private foundations that provide grants and other support for innovation and/or scaling.

| Table 1. Case study organizations by funder category | ||

| Type of organization | Name | Focus Areas |

| Multilateral Development Banks | Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) | Multi-sectoral; Latin America |

| African Development Bank (AfDB)* | Multi-sectoral; Africa | |

| World Bank* | Multi-sectoral | |

| Bilateral Official Funders | Agence Française de Développement (AFD) | Multi-sectoral |

| Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) | Multi-sectoral | |

| USAID Feed the Future (USAID-FtF) (2 studies on agricultural funding) | Agriculture, food security and nutrition | |

| Multilateral Vertical Funds/UN Agencies | Global Financing Facility (GFF) | Health |

| International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) | Agriculture, rural development and food security | |

| Systematic Observations Financing Facility (SOFF) | Weather and climate observations | |

| Adaptation Fund (AF) | Climate adaptation | |

| Standards and Trade Development Facility (STDF) | Sanitary and phytosanitary trade in agriculture and food | |

| Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)* | Agriculture, rural development and food security | |

| Innovation and Research Funders (official) | Grand Challenges Canada (GCC) | Health |

| Consultative Group in International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) | Agriculture, food security, climate change, nutrition and environmental sustainability | |

| HarvestPlus (Research) and HarvestPlus Solutions (Commercial Delivery) | Agriculture and nutrition | |

| IDB Lab | Latin America | |

| USAID-FtF (Research) | Agriculture, food security and nutrition | |

| Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC-Research and Innovation) | Multi-sectoral | |

| INGOs | CARE | Multi-sectoral |

| Catholic Relief Services (CRS) | Multi-sectoral | |

| Foundations | Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture[37] | Agriculture and food security for smallholder farmers |

| Echidna Giving | Girls’ education; India, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania | |

| DG Murray Trust (DGMT) | Combatting inequality; South Africa | |

| Gates Foundation | Multi-sectoral | |

| Lincoln Institute of Land Policy | Land policy | |

| Lever for Change (LFC) | Multi-sectoral | |

| Co-Impact | Health, education, economic opportunity, gender equality | |

| Fundación Corona | Education, employment, citizen engagement; Colombia | |

|

It is important to note a few caveats. First, the case studies are neither a random nor a representative sample. As noted above, cases were drawn from organizations that were known to have made some efforts at mainstreaming. Second, selection required cooperation from the organization. Third, the case studies do not represent nor were they meant to be formal, in-depth, independent evaluations. Rather they are joint learning efforts undertaken by the funder organizations and the SCoP with limited resources and time. In the interest of bringing to bear as much relevant evidence as possible, the SCoP team selectively augmented evidence from the case studies drawing upon the team’s decades of experience with funder practices and scaling beyond the case studies. Finally, the Mainstreaming Initiative in general and most of the individual case studies did not assess whether greater mainstreaming of good scaling practices led to organizations doing more scaling, nor whether it led eventually to increased sustainable impact at scale commensurate with the size of the problem. The SCoP fundamental theory of change – greater mainstreaming à more scaling à increased impact at scale – is at the core of the Community’s decade-long work and has found substantial empirical evidence to support it as reflected in many of its studies and events.

II. Funder Roles and Progress on Mainstreaming: Setting the Stage

A. Funder Roles

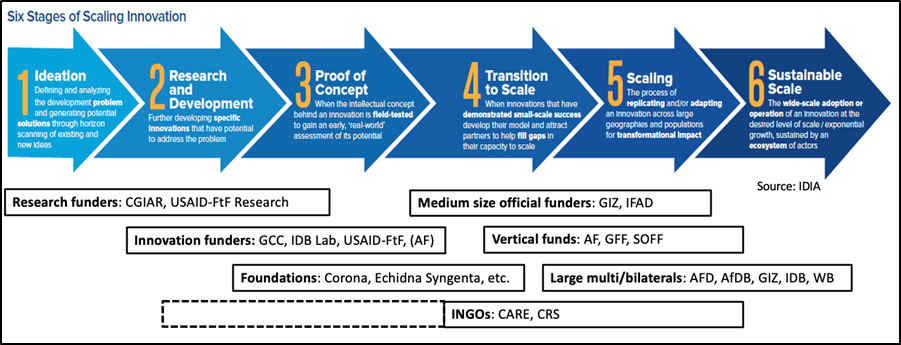

Using the six International Development Innovation Alliance (IDIA) innovation and scaling stages, we characterize funder roles according to where they operate along the innovation-scaling spectrum, from ideation, research and development, proof of concept to transition to scale, scaling, and operating at scale. As demonstrated in Figure 1 (next page), different types of funders support different stages along the scaling pathway, with research and innovation funders focusing on the early stages, foundations and INGOs the middle stages, and official funders, including vertical funds, the latter stages.

Figure 1: Six scaling stages at which funders could support scaling, within their mandates and resources

There are funders across each of the six IDIA stages and many funders overlap two or more stages. In principle, this suggests that the entire scaling pathway is potentially populated with relevant funders and that effective hand-offs from one funder to another are possible. However, the case studies and other evidence demonstrate that, in practice, there are significant gaps in funding support along the scaling pathway. Only some innovation and research funders anticipate and plan for the needed handoffs. Funders who could support scaling and institutionalization do not systematically integrate innovations developed by other funders and instead implement one-off projects at a limited scale. The tendency to go it alone is often reinforced by accountability, branding, and procurement systems rather than by lack of awareness. Thus, overlap alone does not ensure effective handoffs, which depend on incentives, mandates, and deliberate coordination rather than proximity along the pathway.

This predisposition to “go it alone” limits funders’ ability to scale their own projects or to support scaling of innovations that may have developed elsewhere. In particular, research and innovation funders (operating at stages 1-3) report very limited success in handing off proven initiatives to project funders (stages 4-6). By way of example, there has been no systematic process of integrating agri-food innovations developed by the CGIAR with large funder agri-food projects, such as those of IFAD. However, CGIAR is now focused more explicitly on scaling.

The capacity to integrate innovations into large-scale operations is limited even when both functions occur within the same organization. For example, while the incorporation of interventions developed by USAID’s Feed the Future Innovation Laboratories into its projects did sometimes happen, examples are few and opportunistic rather than systematic. The same holds true for IDB-Lab and IDB. This limited coordination between research and innovation funders and project funders contributes to the well-known “valley-of-death” between innovation and scaling. In this regard, it is encouraging that a growing number of research and innovation funders are now funding stage 4 (‘Transition to Scale’), helping ensure that innovations are scale-ready and supporting partnerships

Similarly, evidence from the case studies suggests that few funders and implementers systematically plan for hand-offs to government, private business, and/or other funders for sustainable operation at scale, i.e., stage 6. As a consequence, innovations and project interventions often neglect to align with prevailing implementation modalities and capacity, budgetary resources, or viable business models.

A final important consideration regarding funder roles is the extent to which funders serve as facilitators or intermediary institutions in support of systems change by providing or funding policy advice, capacity building, coordination and investment mobilization. The case studies contain noteworthy examples of funder organizations that extend their roles beyond funding to support field building and systems change in these ways. But this support remains the exception rather than the rule. Intermediary roles require sustained capability and legitimacy, and cannot be treated as short-term or ancillary function. A related challenge for those funders functioning as intermediaries is to ensure that these intermediary functions transition to other, preferably national, institutions after their engagement ends. The potential role of funders as catalytic intermediaries, and case study examples of funder efforts designed to fill this role, are addressed in Section III.I.

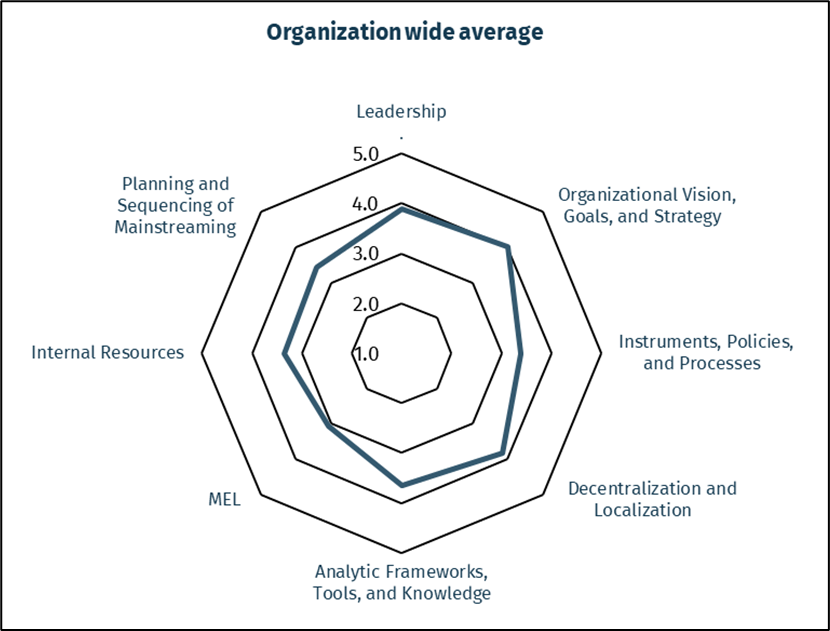

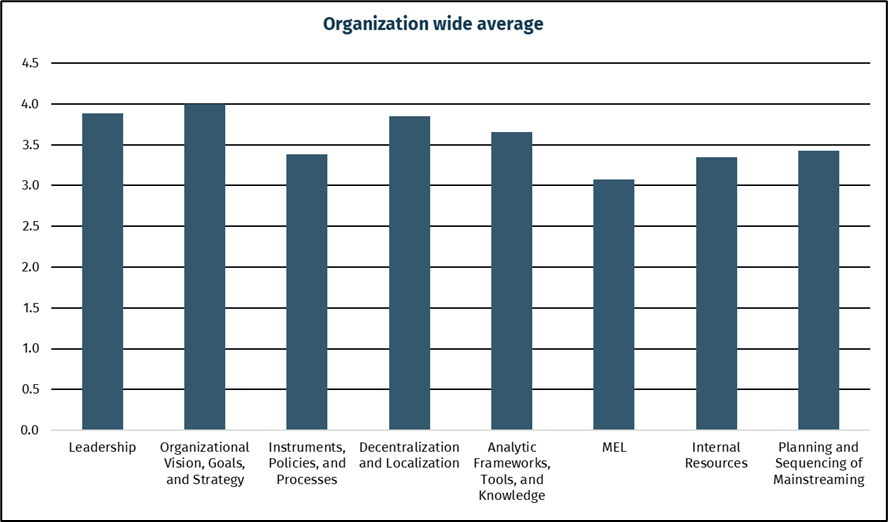

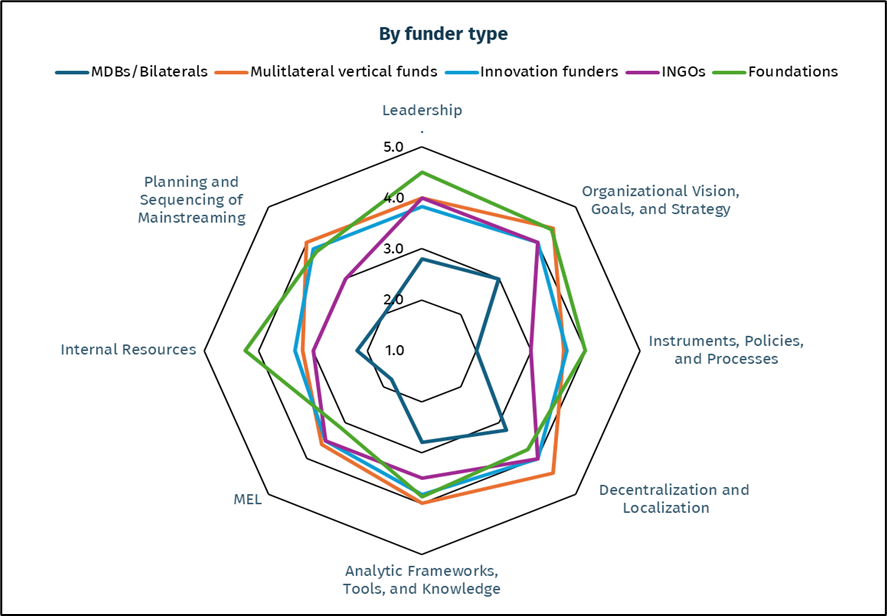

B. The State of Mainstreaming Scaling

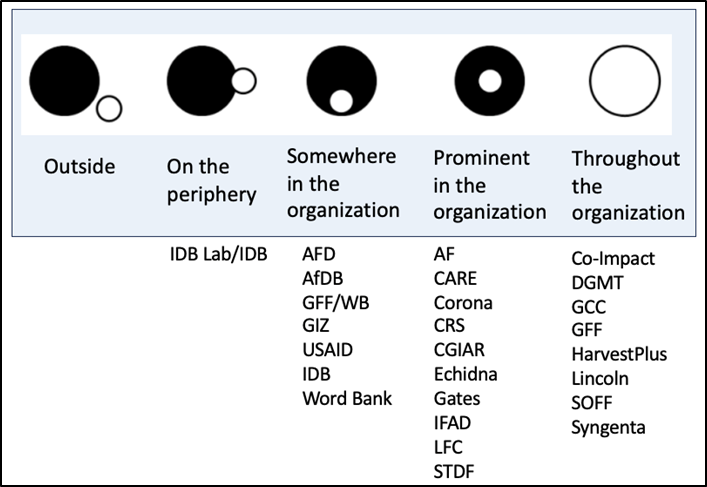

The case studies provide insight into the current state of mainstreaming scaling in funder organizations. At the simplest level, we use a graphical framework for describing the state of mainstreaming within funder organizations as shown in Figure 2 (next page). The framework employs five categories of progress in mainstreaming: (i) scaling is outside the organization; (ii) scaling is on the periphery of the organization; (iii) scaling is prominent somewhere in the organization; (iv) scaling is located at the center of the organization as a key corporate goal, but not implemented throughout; and (v) scaling is intrinsic to the organization. The broad criteria for placement of a funder organization along this spectrum are shown in Table 3.

Figure 2: Funders placement on the mainstreaming spectrum

Table 3: Criteria for categorizing funders by state of mainstreaming

| Incorporated into corporate-level vision, goals | Toolkits and Frameworks developed | Integrated into Strategy, Operations and Procedures | Adoption or Utilization Level | |

| Outside | Not | Not | Not | Not |

| On the periphery | May be mentioned | Not for the organization |

Not

|

Ad hoc |

| Somewhere in the organization | May be mentioned | Developed or relatively advanced for parts of the organizations | Not systematically yet, or still being operationalized | Ad hoc, low levels, not required |

| Prominent in the organization | Central to the organizations’ core goals | Developed or well advanced | Relatively advanced | Started, still a small percentage |

| Throughout the organization | Central

|

Developed

|

Largely integrated

|

Throughout most of the organization |

Source: Authors

Note that the placement of funders in Figure 2 is only indicative and a snapshot at a particular time and also doesn’t reflect whether the organization is on the continuum from one stage to the next. For example, the World Bank and the IDB are now beginning to focus more systematically on scaling from the top down. And the CGIAR is moving rapidly towards mainstreaming the scaling agenda throughout its member organizations and hence could soon be categorized as falling into the “intrinsic” group. Furthermore, while in general it would be desirable for funders to move from left to right in Figure 2 (or from top to bottom in Table 3), not all funder organizations should necessarily aim for the “throughout” outcome in their mainstreaming efforts. For example, organizations that fund emergency humanitarian assistance may choose to be somewhere toward the center.

Overall, the case studies support the conclusion that funders are paying more attention to scaling than they have in the past. All the funders in the case studies are at least doing some scaling within their organization (Figure 2). Moreover, the case studies confirm that many funders are making efforts to move from left to right across the mainstreaming spectrum.

The following cases exemplify the status of mainstreaming in the case studies compiled for this Initiative:

- Eight funders (GCC, GFF, HarvestPlus, Lincoln Institute, SOFF, Co-Impact, DGMT, and Syngenta Foundation) stand out with intrinsic scaling for their organization. These funders made significant efforts and progress over the last 5-10 years, if not longer, in mainstreaming scaling throughout their organizations with strong leadership from the top. They have systematically oriented their funding (and delivery) practices to support that decision. For each of them, the case study extracted lessons and suggestions for further strengthening their scaling efforts. For many of these funders the principal driver and form of mainstreaming was the adoption of scaling as an “whole-of-the organization” mandate in terms of culture and purpose, and less about putting in place specific scaling tools, frameworks, incentives, and instruments.

- Ten funders (Adaptation Fund, IFAD, CARE, CRS, CGIAR, IDB-Lab, Echidna Giving, Gates, Fundación Corona, and LFC) have placed scaling centrally in their organizational vision, mission, and goals with strong leadership from the top. In most cases, scaling is prominent in some, but not all, of these organizations’ areas of activity. It is not clear in some of these cases if there is an organizational consensus to move further on mainstreaming (making it “intrinsic”) or whether they have decided that “centrally” is what is appropriate for their organization. However, all these organizations are still in the process of rolling out scaling throughout their organizations and with continued efforts some of them at least can be expected to move into the last column in due course (such as CGIAR).

- Six funders (AFD, AfDB, GIZ, IDB, USAID-FtF, and World Bank) are shown in the middle column, indicating that scaling has been pursued somewhere (and possibly in multiple locations) in the organization, but it is neither at the core of the funder’s mission and vision nor systematically mainstreamed into the overall funding practices of the organizations. As noted earlier, the World Bank may currently be moving to the right, as is the IDB, since their leadership is now focused on pursuing impact at scale. However, what approach to scaling, and where that falls on the spectrum from transactional to transformational (see Section III below), remains to be seen.

- Figure 2 also identifies two funder pairs. The GFF/World Bank pair is placed in the middle column, since the GFF is a trust fund housed at the World Bank, and GFF and the World Bank collaborate and cofinance in support of impact at scale. The IDB-Lab/IDB pair is in the second column from the left, since the IDB-Lab case study notes that there are as yet few effective links with IDB programs. Therefore, the pair is considered to have mainstreaming “on the periphery”, while IDB Lab itself has mainstreaming “at the center of the organization.”

Three additional findings emerge from the overall mainstreaming experience of funders included among our case studies:

- It appears that funders with narrower mandates and/or less reliance on appropriated funds have made more progress in mainstreaming scaling than official funders with broad, multi-sector mandates. The latter – official bilateral funders or multi-lateral development banks – face greater internal bureaucratic obstacles, disincentives and inertia, and find it difficult to adjust their traditional one-off project funding approach. Key informant interviews suggest that this may be due, in significant measure, to the following factors: (i) these funders are accountable to national legislatures or boards of directors that are hyper-focused on limiting the potential misuse of appropriated funds and have little tolerance for failure and high risk-aversion in terms of any perceived waste of taxpayers’ money; (ii) monitoring, evaluation, accountability, and incentive systems that focus on disbursements, short-term outputs, and direct beneficiaries, with little consideration of collective impact and indirect attribution; and (iii) a lack of explicit or implicit guidelines that allow for longer time horizons, multiple rounds of funding, and strategic pivots.

- In response to increased pressure to realize the promise of their investments in innovation, research and innovation funders are pushing further downstream into funding stage 4 (“Transition to Scale”) along the scaling pathway in Figure 1, helping to ensure that innovations are scale-ready, and are doing more to support partnerships and to broker follow-up funding.

- Mainstreaming is a long-term process. IFAD has been working to elevate the scaling agenda for twenty years and it remains a work in progress. For other funders (GIZ, CRS, CARE, Harvest-Plus, etc.), it has been 10 or more years of progressive efforts to mainstream scaling. The CGIAR began serious mainstreaming efforts around 2020 and launched its Scaling for Impact (S4I) program only at the beginning of 2026; it expects S4I to continue until the end of the decade. While the Standards and Trade Development Facility (STDF) has been taking some actions that support scaling since its inception in 2006, scaling was only formally integrated into its strategy in 2025.

The remaining sections of this report dig more deeply into the scaling experience of the case study funders. We begin with the next section by addressing what scaling practices funders should and do support, and in the subsequent section how funders can and do mainstream the support for these scaling practices into their operational approach.

III. Transformational Scaling Practices

Funders need to focus on transformational scaling, not merely transactional scaling. This is a foundational aspect of good scaling and a major new insight generated by the Mainstreaming Initiative. As defined by the SCoP, transformational scaling emphasizes sustainable, long-term outcomes at scale in contrast to transactional scaling which focuses on mobilizing more money to undertake more and larger projects with larger impact by the end of the project (Box 3). Support for transformational scaling prioritizes continued post-project scaling by permanent, preferably domestic, actors funded by permanent, preferably domestic, resources to achieve a well-defined, long-term goal. Among the case studies included in this study, there are examples of funder organizations that incorporate an explicit focus on support for transformational scaling. However, a transactional approach remains more typical.

| Box 3: Distinguishing between transformational scaling and transactional scaling

There is a continuum from purely transactional to fully transformational scaling. We describe the end points of that continuum, understanding that many projects and interventions fall somewhere in between. Transformational scaling takes place when initiatives, innovations, or projects are pursued with full attention to long-term, sustainable, scale goals and potential pathways to achieve these goals. Transformational scaling is demand driven and grounded in local ownership and sustainable funding. Initiatives, innovations, or programs are designed, implemented, and evaluated as steppingstones to achieve goals with explicit reference to addressing systemic barriers and ensuring enabling conditions exist for sustainable scaling. Sustainability occurs by identifying, and strengthening where necessary, local actors with the necessary mandates, incentives, resources, and implementation capacity, whether public or private, and persuading them to take on the roles of ongoing financing and implementation. This often implies that scaling is combined with systems changes and policy reform. Impact is measured in relation to the long-term target such as: “The number of women of reproductive age using basic reproductive health services moves from current levels of 30% to 75% over the next decade.” Or: “Carbon dioxide emissions reduce by five percent of the long-term emissions reduction target.” Transactional scaling focuses on larger projects and additional project financing, and frames results in terms of the direct impact specific projects are expected to achieve – or have achieved – at completion. Transactional scaling does not typically include systematic plans for what happens beyond the project’s end; does not take significant steps to mobilize or facilitate ownership by local actors who could ensure sustainability and scalability; and is often supply-driven. Capacity building, systems strengthening, and addressing the enabling conditions are typically limited, if they occur at all, and largely focus on ensuring achievement of the project’s short-term objectives. Most often, transactional scaling impact is considered in absolute terms or in relation to a baseline, but not in relation to a long-term need or target. Examples include: “10,000 women will access reproductive health care through our project.” Or: “Carbon dioxide emissions will be reduced by five percent as a result of our project.” |

Source: Authors

The remainder of this section unpacks eight key elements of transformational scaling, drawing on the principles noted in relevant SCoP publications (Scaling Principles and Lessons and Scaling Fundamentals) and the scaling guidance published by OECD-DAC as well as the cumulative experience of our 28 case studies. For ease of reference, these eight practices are shown in Box 4.

| Box 4. Eight transformational scaling practices

A. Initiate scaling from the beginning B. Incorporate scalability assessment C. Integrate systems change with scaling support D. Consider equity and inclusion explicitly E. Double down on country ownership and localization F. Invest in partnerships with other funders G. Build support for scaling into MEAL H. Elevate the role of intermediaries |

A. Initiate Scaling from the Beginning (“Start with the End in Mind”)

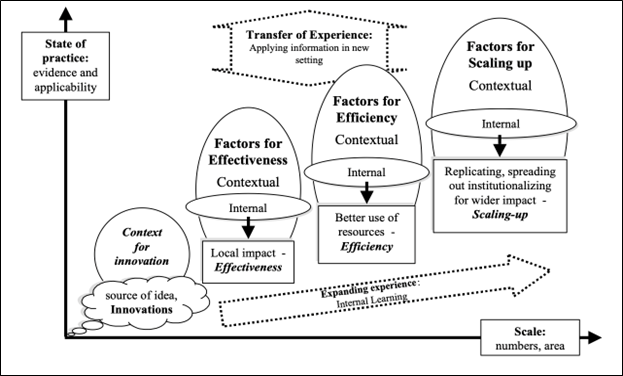

An early popular scaling framework suggests focusing first on effectiveness (or the depth of impact on individuals), then on efficiency, and finally on expansion (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Scaling at the end rather than the beginning: A discarded approach

The scaling literature and the SCoP’s scaling experience reject this formulation as likely to result in interventions that maximize a project’s immediate impact (per location, end user, or beneficiary) at the expense of scalability and breadth or reach (as well as equity, social inclusion, and sustainability) by including elements that later prove to be difficult or impossible to deliver at scale. Instead, it is critical to focus from the beginning of an innovation process, a pilot project, or any intervention on likely scaling challenges, and, as discussed below, explicitly confront the fact that scaling faces multiple objectives necessitating tradeoffs between them. This implies working to establish the foundations for scaling even before knowing that an innovation or intervention merits broader application – what has been called proceeding with “one foot on the accelerator and the other on the brake”. Designing for scale early does not imply lowering standards of effectiveness, but rather redefining effectiveness in ways that remain feasible at scale.

Here the story emerging from the SCoP case studies is somewhat encouraging. The case studies suggest that a growing array of funders focus on scaling early in the innovation or project preparation process (e.g., CARE, CGIAR, CRS, GCC, IFAD, Lincoln Institute, SOFF, Syngenta Foundation, and HarvestPlus). However, for many funders, especially the larger ones, getting project teams, managers, and quality assurance units to focus adequate attention on scalability and the scaling agenda during project preparation remains a challenge. Middle managers note the pressure of having too many other corporate priorities and external critics observe that funders with larger projects and greater funding sometimes mistakenly conflate project scale and transformational scaling.

B. Incorporate Scalability Criteria and Assessment

Good practice suggests the practical utility of incorporating early use of “scalability assessments” to establish whether an innovation or intervention is scalable and under what conditions. While multiple scalability assessment tools have been developed for different sectors and by different organizations, the tools that we reviewed share many common elements and serve more or less the same functions: (i) to help determine whether an innovation or project is suitable for scaling; (ii) to assess what may have to be adjusted in the design of the intervention in the face of systemic constraints; and (iii) to identify accompanying system changes needed to address constraints. They also support a shared definition within the organization of what scale means and understanding of scalability that facilitates internal cohesion around that goal. Perhaps most importantly, the value of early scalability assessments lies less in the application of the tool itself than in how rigorously the findings influence go/no-go investment decisions and design revisions as innovations advance towards scaling.

Among the case studies we prepared and reviewed, we found several cases of organizations that recognize the need for an explicit scalability assessment and that have developed and used tools to conduct such an assessment. Particularly noteworthy were versions developed by CGIAR, GCC, IDB-Lab, CRS, and CARE. CGIAR’s tool is particularly advanced and complex. It requires identifying all complementary innovations relative to a core innovation (the “Innovation Package”) and conducting context, stakeholder, and political economy analyses. These analyses are used to determine bottlenecks and to develop actions needed to address those bottlenecks. GCC includes scaling potential among its general grant making criteria, and scaling is at the core of its funding instruments that target transition to scale. Some funders pay special attention to the financing constraints to sustainable scaling (e.g., GFF), while others focus more on policy and institutional strengthening (e.g., GIZ and GCC). IFAD’s scalability assessment involves systematic consideration of enabling conditions (or “drivers and spaces”). USAID-FtF developed a detailed guidance document on scaling, the Agricultural Scalability Assessment Tool and a tool – “Innovation to Impact” (or i2i) – that applies criteria used by private agri-business to decide whether to invest in innovations as they move through the stages of research, development, and testing by establishing what they call “stage gates.”

C. Integrate Systems Change with Scaling Support

As noted above, systems change is typically a critical element of transformational scaling. At a small scale and for one-off projects, funders and their implementing partners and grantees frequently have sufficient financial and institutional resources to address or work around systemic obstacles. However, solutions that match the size of the problem, especially if that scale is national and regional, inevitably encounter additional systemic obstacles that can severely constrain or prevent scaling.

National public policy, legal, and regulatory environments are obvious examples of systemic constraints, along with the capacity of potential public or private sector implementers. Another common constraint is a lack fiscal space in cases where the public sector is expected to defray some or all of the costs associated with implementing or subsidizing changed practices at scale. The political economy of systems change also creates obstacles since systemic reforms do not only have winners, but also losers who will try to impede or reserve the reforms unless they are compensated or restrained through the political system. Surrounding these issues are an array of existing power dynamics, social norms, and beliefs, all of which become more apparent and constraining the more significant the change and the greater the scale of impact.

Most large official funders support systems change in some way. Among the bilateral official funders, GIZ, for example, supports activities that help build government capacity and change the public sector enabling environment. The MDBs routinely support system reform, as do vertical funds in their specific areas of engagement. However, very few of the larger organizations in our sample coordinate their investments in systems change with the needs of scaling. Their support for system reform tends to be one-off in nature, rather than sustained for lasting impact, and tends to be disconnected from their project funding in the countries concerned. GFF, IFAD, and SOFF are exceptions, incorporating into their projects’ short-time frames and output-oriented approach as much capacity building and systems change as possible given the time and resources available.

Integrating systems change is a challenge for smaller funders and those working on innovation, as their mandate is to focus on the innovation, not the system. Nonetheless, GCC, CGIAR, and a growing number of innovation funders have taken steps to integrate systems change, as far as possible with their limited resources. The same is true for many of the private foundations included in our sample. For example, CGIAR routinely strengthens national agricultural research and extension services and provides policy advice. Private foundations include notable cases of direct support to local ecosystem change in targeted countries and sectors by the Gates Foundation, Co-Impact, Echidna Giving, and Lincoln Institute. Notably, Co-Impact features an explicit and central focus on systems change in each of its grants. In regard to land policy, the Lincoln Institute is an example of a think tank that focuses systematically through research, training, advice, and communication on helping to create a policy environment for effective land policy and financing at a global scale.

The relationship between scaling and systems change reinforces the need for effective partnerships between organizations that invest in research and innovation, organizations that focus on project implementation, and organizations that focus explicitly on systems strengthening. A notable example among small funders is Syngenta Foundation’s investment in the Seeds to Be (SEEDS2B) program (co-funded with USAID’s Feed the Future program). SEEDS2B worked to strengthen seed systems, helping domestic companies with licensing of new varieties and commercialization; strengthening and streamlining national testing, licensing and registration systems; and harmonizing regional systems. This allowed for faster release and scaling of new, improved varieties, clear scaling (commercialization) pathways, and reliable, sustainable seed supply chains. However, this example also demonstrates the challenges for advocates of scaling within funders; USAID’s scaling team was not able to obtain funding to replicate this systems approach in other agri-food subsectors such as mechanization and machinery services.

There is also an inherent tension between scaling and systems change. Systems change takes time, energy, and focus that can compete for attention and resources from scaling in the narrow sense. In Ghana, Feed the Future worked with the Ministry of Food and Agriculture to restructure its institutional approach to National Performance Trials while concurrently collecting the data required by the trials. Keeping the reforms and the trials moving in lockstep required very deft management so that the reforms would not derail the trials.

D. Consider Equity and Inclusion Explicitly

It is necessary to consider not only absolute scale of impact but also the sustainability and distribution across different social groups as scaling can have an intrinsic tendency to increase inequities because there are almost always lower transaction and other costs to scaling to advantaged groups that benefit from better infrastructure or population density. This has given rise to the concept of “optimal scale,” i.e., the scale that best balances quantitative and distributional goals most effectively. Most funders specifically include gender and other equity and inclusion objectives in their efforts to support the pursuit of scaling, whether it is small-holder farmers (e.g., Syngenta), people who live in remote areas (e.g., IFAD), women and children (e.g., GFF), the distributional implications of land policy (Lincoln Institute), or other equity and inclusion targets. CARE puts gender and gender equity at the center of its work. One of CRS’s scaling principles is to “engage with systems actors, both traditionally underrepresented and existing decision-makers, to prioritize equitable scaling.” However, the explicit consideration of the potential tension between scale and equity/inclusion has received less attention in our sample. Optimal scale calls for explicit consideration of the variety of unintended consequences associated with scaling including compensation for those displaced or disadvantaged by the changes resulting from new policies and practices. Only a few funders, e.g., CGIAR, CRS, GCC and SDC, make explicit their commitment to optimal or responsible scale principles, and even for these implementation remains a work in progress.

E. Double Down on Country Ownership and Localization

The pursuit and achievement of sustainable impact at scale requires ownership and involvement in decision-making by host country stakeholders of the goals and interventions supported by funders, and especially scaling strategies and objectives. This is in marked contrast to the lower bar of host country “concurrence” and stakeholder consultation evident in many donor-funded projects and programs. Accordingly, what is now often referred to as “localization” provides an important underpinning for effective and sustainable scaling. This includes not just the national government or alignment with national strategy documents, but broad stakeholder engagement with civil society and the private sector. It also means a search for locally sourced innovations and ensuring that there is effective demand for the goods and services created in a scaling process. It implies support for and use of local capacity and systems, the incorporation of sustained sources of public or private finance, and preparing for effective hand-off at project or program end to national organizations.

Notably, this focus on scale is at odds with some forms of hyper-localization that focus interventions on a limited number of small, local, community-based actors with little regard for geographic spread, external validity, or business models at scale. Financial and especially commercial viability can be impossible to achieve without a certain minimum market size.

Several of the organizations featured in case studies make use of “country platforms” as a means to combine localization with a recognition of the multi-stakeholder collaboration needed for effective scaling. For example, GFF supports the development of inclusive country platforms for maternal and child health programs. These platforms bring together an array of national stakeholders, including concerned government ministries, representatives from the private sector and civil society, as well as external funders, to jointly develop a sector strategy, implementation modalities, a results-tracking approach, and MEAL activities. As explained in Box 5, country platforms and scaling are mutually reinforcing as long as they are designed to support transformational long-term development and climate action.

| Box 5. Country Platforms and Scaling

Country platforms are nationally led coordination mechanisms that align government, external funders (MDBs, bilateral donors, philanthropies), private actors, civil society, and technical agencies around a shared, long-term development or climate vision. In general, they serve four core functions: (i) strategic alignment with national plans and strategies; (ii) coordination of actors to reduce duplication and fragmentation; (iii) mobilization of domestic and international finance; and (iv) MEAL to adapt during implementation. Effective platforms require an institutional home (a secretariat) that convenes partners, manages inclusive consultation, curates a common evidence base, and runs MEAL. Multilateral facilities such as the GFF (health) illustrate how an external facility can help countries stand up and animate a platform, at least until national institutions can fully take over. Country platforms are well suited to tackle common scaling barriers by (i) mobilizing or brokering resources to cross the “Valley of Death” in scaling between small pilots and follow-on projects along a scaling pathway; (ii) support sustainable institutionalization by convening, coordinating, and aligning support by national stakeholders; (iii) help overcome fragmentation and short time horizons by aligning programs and funding behind long-term national scale goals and pathways rather than one-off projects; (iv) address weak enabling environments by creating a locus to sequence policy and institutional reforms needed for durable delivery at scale; (v) closing the evidence-to-action gap by encouraging MEAL and adaptive learning; (vi) closing the financing gaps by effective fiscal planning and risk-sharing through public-private financing instruments; and (vii) aligning incentives and accountabilities across government, donors, implementers, and investors. At the same time, if country platforms are to help achieve long-term development and climate goals, their participants need to have internalized a scaling focus in their own operations, ensuring that their front-line teams have the incentives and resources to align on a sustained basis around common goals and long-term scaling pathways and engaging in long-term partnerships and coordination efforts. And, common monitoring and evaluation approaches must be implemented with a transformational perspective, incorporating key scaling aspects. Finally, the costs of platform management, coordination, analytics, and incentive mechanisms are real and substantial, and must be transparently budgeted and financed, not treated as unfunded mandates. In short country platforms and scaling are mutually reinforcing. Platforms become effective when they embed transformational scaling logic; transformational scaling, in turn, generally requires a platform to align actors, policies, and finance over time. Source: Linn (2025), op. cit. |

While many funders preach the benefits of national ownership and localization, many also noted challenges in implementing their good intentions. Challenges are especially severe for official bilateral funders since their leadership, parliaments, and ultimately the taxpayers often find it difficult to forgo the pursuit of their national priorities.

Staff and managers in some funder organizations also noted that national ownership, while necessary for long-term sustainable scaling, is no guarantee of success. National priorities shift unpredictably with election cycles, government overhauls, and economic and social crises, disrupting the best-laid scaling plans. Evidence from the case studies demonstrates that support is needed from multi-stakeholder engagement and coalitions are needed to sustain scaling in the face of such changes, i.e., political sustainability needs to be assured. Mobilizing and sustaining such coalitions requires an ongoing country presence and long-term relationships that are difficult to create or maintain when work on the ground is project-by-project and supported from abroad with intermittent expert visits. This is reinforced by the fact that most donors’ MEAL systems are still optimized for accountability rather than for learning under uncertainty, which limits their usefulness for scaling.

Particularly notable examples of funders fully and patiently integrating themselves into local ecosystems were evident in the experience of national foundations like Fundación Corona in Colombia, DG Murray Trust in South Africa, the Nilekani Foundation in India, and the Lemann Foundation in Brazil. Fundación Corona is a particularly instructive example. Blending features of a traditional funder, community foundation, and operating foundation, the Fundación is intervention agnostic and works to form and support coalitions of local actors at a municipal level jointly committed to working constructively with government to solve a problem of national consequence. For every dollar the Foundation commits, it helps local actors mobilize another $7+ dollars and seeks national scale by replicating the same process in multiple municipalities. Other relevant features are its deep commitment to institutional strengthening of local actors and obsessive commitment to the use of performance data.

In a somewhat analogous way, DG Murray Trust maximizes the use of its credibility as a nationally funded, nationally focused, and highly respected actor in South Africa to provide a vehicle for an array of host-country actors to engage constructively with the government on a range of social issues.

INGOs such as CRS and CARE – and many of the international private foundations – make special efforts to engage with multiple stakeholders on the ground, especially market and civil society actors, to help ensure that support remains even when governments and their policies change. Among bilateral funders, an instructive example is the innovations funded by SDC’s TRANSFORM program which requires projects to include partnership with at least one local research organization and an implementing organization, usually a domestic NGO.

Finally, as elaborated in Section IV below, many international funders have pursued decentralization of their operational staff to national or regional offices, closer to their programs and clients. This should, in principle, help with generating local ownership, building partnerships on the ground, and monitoring progress and constraints to scaling innovations and projects. However, experience from the case studies suggests that decentralization alone does not necessarily mean stronger localization or better scaling. Ironically, some funders note that decentralization can actually make scaling more difficult organization-wide. In decentralized organization, when the imperative to scale comes down from headquarters without creating buy-in from staff members based in country offices, the latter have few incentives and capacity to support, systematically embrace, and implement those approaches. Feed the Future experienced this as USAID missions design and fund their agri-food (and other) projects from their own budgets.

F. Invest in Partnerships with Other Funders

As noted above, there is broad agreement and growing evidence that enhanced coordination, partnership and collaborative funding are needed to overcome problems inherent in the highly fragmented development assistance architecture.

This is especially important for scaling interventions where host governments play dominant roles. Here, the case studies demonstrate remarkable strategic change in many funders’ theories of change in the last decade. Where the problem used to be research and innovation funders and private philanthropists that failed to recognize the central role of governments in achieving and sustaining development and climate results, the problem now is the challenges and bottlenecks created by multiple organizations hoping to work with and through government to advance their preferred issues and initiatives. On the other hand, the cases also demonstrate that the rhetoric of partnership often outstrips the reality. Where platforms for partnerships, collaboration and pooled funding exist, they are too often single-purpose and transactional, prioritizing cofinancing over joint problem solving and limiting the scope for effective hand-offs from one partner to another. While these partnerships sometimes result in larger one-off projects, they frequently lack longer-term longitudinal strategies for sustainable scale.

At the same time, there are notable exceptions. The Adaptation Fund actively seeks to partner with others (so far primarily with the Green Climate Fund) to hand projects over for scale-up once its projects are finished. Similarly, the Gates Foundation regularly partners with multilateral co-financiers, especially MDBs like the World Bank, IFC, and African Development Bank, to co-finance both scaling efforts and complementary investments. In recent years, the CGIAR has been working actively and successfully to integrate its innovations into national agri-food strategies in Africa and into the projects of the African Development Bank and other donors.

More generally, few funders offer evidence of having focused explicitly on the challenges of effective collaboration and coordination. There are staff and budgetary costs to develop and maintain partnerships; there are disincentives for managers and front-line teams when speed of project preparation, number of projects delivered to the governing boards, and amounts of money disbursed are the key performance measures; there are issues of control and meeting specific fiduciary requirements; and many funders are loath to dilute their brand and forgo the ability to literally plant their national or institutional flag at project sites.

G. Build Support for Scaling into Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning (MEAL)

Evidence from the case studies confirms what has become the conventional wisdom in the field of scaling: that successful scaling is normally a lengthy process – typically takes 10-15 years – and rarely unfolds in accordance with initial plans. The process requires a commitment to genuine adaptive management and MEAL systems geared to support the iterative nature of scaling, from initial design of interventions all the way to sustainable scale. MEAL can identify and engage viable “doers” and “payers” for delivering goods and services at scale to identify strategies and manage progress in implementing new practices, strengthening institutions, shifting social norms, and addressing potential losers from scaling.

To meet these needs, MEAL systems need to go well beyond assessing whether an intervention or innovation “works” (i.e., has been implemented in an efficient, effective, and timely manner according to plan and has a positive impact), but also whether it is sustainable, scalable, and ultimately whether it has been sustainably scaled. Prior to full implementation, that includes assessment of the factors and preconditions likely to affect scalability; and during scaling, it includes effectively monitoring the interim changes needed to ensure full implementation, maintain effectiveness, and guarantee sustainability over time. It is also important to track the spread of interventions beyond the direct beneficiaries of specific interventions.

Our work with funders has shown that their MEAL practices are relatively strong in determining direct impact of interventions (proof of concept), are much weaker in assessing scalability and generally do not focus on whether the interventions effectively support scaling.

In a survey of the members of the SCoP’s Monitoring and Evaluation Working Group, the consensus was that – in order to provide for these needs and to secure wide dissemination of the resulting information – budgets for MEAL and information dissemination for pilot projects should be closer to 20% than to the 5-10% more typically provided for typical implementation projects. The case studies did not include any example of a funder having yet embraced this view.

A key analytical challenge in monitoring progress on scaling is assessing the extent to which systems changes and other foundational pieces of scaling are in place and permit or facilitate scaling. The CGIAR, USAID’s Agricultural Innovation Laboratories (part of USAID-FtF), IFAD, Co-Impact, and the GFF are the funders in our case study sample that have most explicitly focused on these considerations. For example, GFF systematically includes specific metrics for system change as part of its monitoring process through its support for a “One Plan/One Budget/One Record” approach in all the countries where it is active.

For most funders, however, MEAL continues to emphasize accountability, planned outputs, benefits to direct project participants, and disbursements. The current OECD-DAC and MOPAN evaluation guidelines for bilateral and multilateral official funders do not focus on sustainable scale or progress towards scaling in their recommended MEAL guidelines. Similarly, the case studies suggest that, for most research and innovation funders, tracking scaling beyond their own engagements and direct beneficiaries continues to be the exception rather than the rule. One notable exception is CGIAR, which is now committed to tracking the progress of its innovations all the way to sustainable scale. Likewise, GCC, which traditionally proxied the scaling impact of the innovations it supports scaling by measuring the funding its grantees raise, has updated that approach to include data on actual longer-term scaling and conducted one-off assessments of the entire portfolio’s progress towards financial sustainability and scale.

To aid in efforts to support and monitor progress towards sustainable scaling, the SCoP developed the Mainstreaming Tracker Tool – a maturity model, tool, and guideline for tracking the extent to which needed changes are institutionalized in host governments.

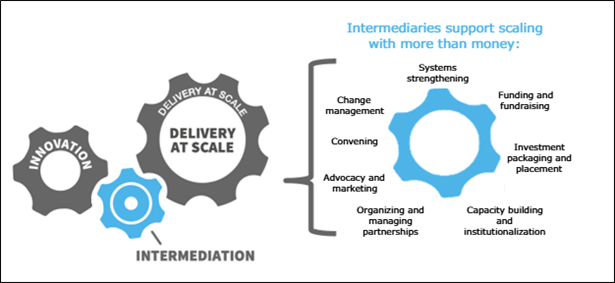

H. Elevate the Role of Catalytic Intermediaries

Catalytic intermediary organizations (intermediaries for short) facilitate the transition from innovations and innovators to large public and private sector delivery systems. As illustrated in Figure 4 below, these functions include tasks such as finding and supporting champions; convening stakeholders and building consensus; packaging investments; providing scaling advice assistance; helping to identify policy and regulatory obstacles; etc. These are tasks typically played by venture capitalists and investment bankers in the private sector. Regrettably, few organizations exist to provide these functions for public goods, largely due to the absence of viable business models for the organizations involved. This gap has been referred to as the broken part of the business model for scaling.

Figure 4. The manifold functions of catalytic intermediaries

Absent a robust ecosystem of public, for-profit or not-for-profit organizations dedicated to intermediation, the responsibility falls on funders to provide or to fund these services. Among our case study partners, GFF, SOFF, CRS, Co-Impact, DG Murray Trust, and Fundación Corona are the organizations that have most comprehensively adopted an intermediary role; and the aforementioned newly initiated CGIAR S4I program is precisely intended to fill this function. Others, including HarvestPlus, IFAD, IDB-Lab, Gates, GCC, the Adaptation Fund, and the Syngenta Foundation provide intermediary support in a more limited fashion.

Many funders, especially innovation funders and foundations, are expanding their efforts to broker a next round of funding for the interventions they support and are providing capacity building to enable their grantees to better access funding and other forms of partnership. Some, like Fundación Corona and DG Murray Trust, provide direct support for capacity building to the implementation, advocacy, and intermediation partners they support. Others, using strategies modeled on Lever for Change’s (LFC) Open Competition model, provide several months of coaching to finalists to improve their proposals, often accompanied by substantial capacity building grants. All LFC finalists, for example, become eligible to participate in the Bold Solutions Network which provides opportunities for networking with other implementers and with potential funders along with a variety of individual and collective coaching and training opportunities. In this way, LFC has mobilized over $2.5 billion in total funding, well above the $1 billion in direct funding.

As more funders and implementers embrace the central role played by governments in achieving sustainable outcomes at scale, many have expanded their attention to working effectively with and through government. This sometimes leads to second-order intermediation problems as funders and implementers competing for government attention create a multiplicity of stakeholder forums and coordination mechanisms intended to ensure the needed buy-in for scaling specific interventions. The cases reviewed during this study also illustrate; however, emerging experience of donor collaboratives, multi-stakeholder country platforms, and other innovative mechanisms better suited to outcomes-oriented and government-led planning and coordination.

Rather than provide intermediation services themselves, some funders choose to fund local organizations to perform intermediation and field building activities. Examples from the pool of case studies include the Syngenta Foundation, GCC, Echidna Giving, and Lincoln Institute. But, such efforts remain small and nascent and, in our view, fostering more explicit consideration of funders’ roles in strengthening and financing intermediary organizations – and in developing viable business models for intermediaries – should be a priority topic for further research.

IV. Mainstreaming Support for Transformational Scaling in Funder Organizations